By C.S. Hagen

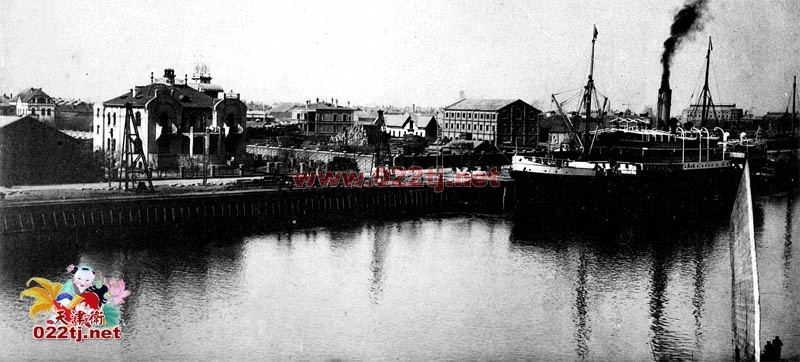

TIANJIN, CHINA – Art was a dangerous and bourgeois calling for young Feng Aidong. At a time when books such as Dr. Seuss’ Green Eggs and Ham were banned across China, when imported trees, namely Dutch elms, were uprooted and used for fuel, few dared to dream of art. In Double Mouth Village, twenty kilometers north of Tianjin, equally anti-revolutionary were green grass, poetry, and sparrows, a once abundant species nearly annihilated during China’s Cultural Revolution Four Pest Campaign.

Art, in all its forms, but one, was counter revolutionary.

“From a young age I loved to draw,” Feng said. “Especially with pencil, like the old Chinese heroes Monkey King and Pigsy, or patriotic soldiers.”

Born into the bloody tumult of the Cultural Revolution, Feng watched with fascination his baba, or father, paint the only pictures the times allowed: Chairman Mao Zedong hailing the masses with his Little Red Book, philosopher Karl Marx against a red background, and Vladimir Lenin with his defiant fist.

His father’s hobby inspired him to paint, but when he picked up the brush at eight-years-old, his father tried to beat the dream out of him.

“Art was no life for a farmer,” Feng said from his Tianjin city apartment. He’s nearing fifty-years-old. His teeth are nicotine stained, and the local Tianjin vernacular gives him an easy-going demeanor despite his six-foot-three-inches and solid 220 pounds. His hands are thick, large for the intricate work he loves.

“My father beat me every time I painted, told me to work harder and study more. But I don’t hate him. He only wanted what was best for me at the time.”

Once, during middle school, a teacher asked Feng what he wanted to be when he grew up.

“I didn’t dare answer,” Feng said. “All I wanted to be was an artist. But who in their right mind could pursue such an interest in those days? A peasant’s life was hard, and didn’t leave time for such pursuits.”

When he was thirteen-years-old, not long after Chairman Mao’s death, Feng saw a folk art exhibition (nongmin hua 农民画) for the first time in Double Mouth Village.

“When I saw the paintings, I knew I could do it,” Feng said. “And I’ve loved folk art ever since.”

Not even his father could keep him from his Chinese wolf-hair brushes, called maobi. The horrors of the Cultural Revolution relaxed after the movement’s instigators, the Gang of Four, were convicted for treason. Grasses grew back. Flowers budded once more, and art classes opened up around the country. Feng studied and worked by day, painting six hours every night, leaving little time for sleep. His father, an engineer by trade, finally relented to Feng’s insatiable pursuit and enrolled him in an art class taught by Zhang Weimin, a teacher he recalls with fondness.

He painted from his memories and his imagination. Never having seen the Great Wall, Feng used the historical motif in many of his paintings. “I loved farmers tilling their fields, planting crops, building their homes. I never took a photograph. Just like today, I went to a place, studied it, returned home to think about it, and then painted my interpretation.”

At eighteen-years-old Feng entered a single painting into the Tianjin Municipal Beichen District Art Competition. Out of 35,000 participants, he received first place.

“I was more than astonished. For the first time in my life I began to hope that my artwork could become my profession,” Feng said. “In those days China was still very poor, we didn’t know what the outside world was like.”

Nobody believed he could relinquish the plow. Feng was not deterred. For five years he worked harder, planting and harvesting corn and millet by day, painting with his water colors at night. An arduous routine, he said, until he was twenty-two, and his dream was realized. A local merchant agreed to sell his paintings. Most of his artwork was sold to international embassies, hotels in the neighboring “big city,” to museums and to visiting travellers from abroad.

Feng stopped his daytime job, and knuckled down to work, churning out hundreds of paintings each year. Tianjin at one time had more than 200 folk artists, Feng said, but sadly, he was the only one who survived professionally.

Feng stopped his daytime job, and knuckled down to work, churning out hundreds of paintings each year. Tianjin at one time had more than 200 folk artists, Feng said, but sadly, he was the only one who survived professionally.

He experienced a scare when his distributor suddenly stopped selling his paintings, and he took to the streets in search of a new buyer, ending up at an art store in Tianjin’s Ancient Culture Street. From here, he said, his artwork began to flourish. Copycats in southern Guangzhou and nearby Beijing have copied his art, attributing his name to their paintings. He’s sued them in court, but as of yet, due to China’s insufficient policies on copyright infringement, he has not seen a Chinese aluminum fen, or the equivalent of one-sixth an American copper penny from the lawsuits. Nor does he expect to see a settlement.

Today, some paintings take Feng two to three years to perfect. After he saw China’s Great Wall for the first time, he made no changes to his own interpretations. “My Great Wall is best,” he said. Another painting, entitled Zhuanchang, or Brick Factory, took him longer than three years to complete.

“I wanted this painting to have a certain feel, and I painted it over and over, but it was no good. So I went back and studied the scene again and again, until I got it right. And it is now one of my favorite paintings.”

“I wanted this painting to have a certain feel, and I painted it over and over, but it was no good. So I went back and studied the scene again and again, until I got it right. And it is now one of my favorite paintings.”

Most days, Feng paints from ten in the morning until after midnight, he said. “I have never once felt tired of painting. Sure, my body grows tired, but not my desire. Never, my desire.”

Feng has won many provincial and national awards for his life’s work, including a recent series called Beauty of China, according to an October 4, 2014 article published in Xinhua News, one of China’s prominent online newspapers. Mostly, Feng’s artwork depicts daily scenes in the ever-changing Chinese village life, but always with an interesting twist, or comic flare. Many of his paintings tell stories that are not easily seen with a cursory glance. When he’s not painting, Feng teaches elementary classes back at Double Mouth Village. He wants his art form, unique and boldly intricate, usually only seen in embroidery or cutouts, to exist long after he is gone.

“My students are the seeds for the future of folk art,” Feng said. “And as my teacher, Zhang Weimin, helped me achieve my dream, I hope to do the same for them, if possible.”

Feng Aidong teaching his students in Double Mouth Village – Tianjin Beichen District Education Portal

Awards and Accomplishments:

Paintings:

1995 – Boiled Fish Paste Cake – second place National Award

1998 – Autumn – second place National Award

2000 – Around the House – third place National Award

2002 – Small Farm House – third place National Award

2010 – Rich People – first place National Award

Feng’s works are displayed in the Art Museum of China, the China Folk Art Museum, and he has been featured in a documentary on Tianjin TV. Feng is also a member of the Tianjin Artists Association, Tianjin Literature and Art Association, and the Tianjin Youth Artists Association. His paintings have been published by the People’s Daily, the Daily Worker, Chinese Art Magazine, Tianjin Daily, Rural Youth, the Beijing Review, Chinese Women, and Farmers Illustrated.

Interested in Feng Aidong’s paintings? Contact me at cshagen@gmail.com. They will be for sale later this year in America and will be on display in The Uptown Gallery in Fargo, North Dakota, soon.