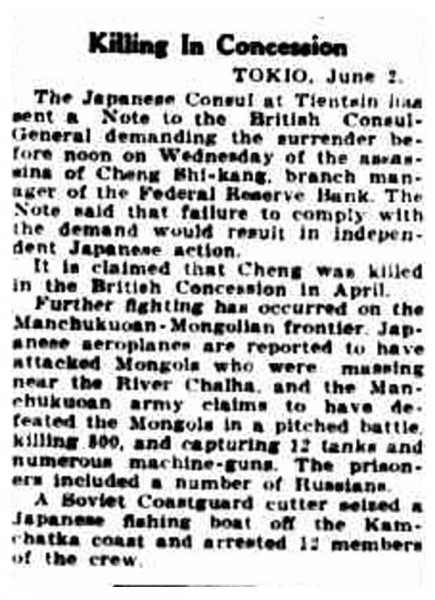

The following is based on the true story of Wu Yuan, sometimes known as Li Chin Fang. Due to the similarities in the missionary reports of both Wu Yuan and Li Chin Fang – orphans – who attended Western mission schools, and whose accounts were written by diametrically opposed Catholic and Protestant hands, the stories have been combined into one true, and epic adventure of Wu Yuan during the Boxer Rising of 1900. Hero or traitor? You, gentle reader, can decide.

By C.S. Hagen

PEKING to TIENTSIN – Little “Almond Eye” squatted in a crenel along the Tartar Wall, above the Sluice Gate while a missionary doctor tied a rope around his waist. Almond Eye, or Wu Yuan, gripped a porcelain bowl half filled with porridge. Beneath the porridge, wrapped in oiled silk, a secret message was hidden.

A nearby cannon belched thunder. Wu Yuan’s thin frame flinched. Sporadic musket fire was followed by a modern rifle tattoo. Somewhere in Peking’s Foreign Legation area, a child wailed. At twelve years old, Wu Yuan knew the sound. Hunger cried the same in any language.

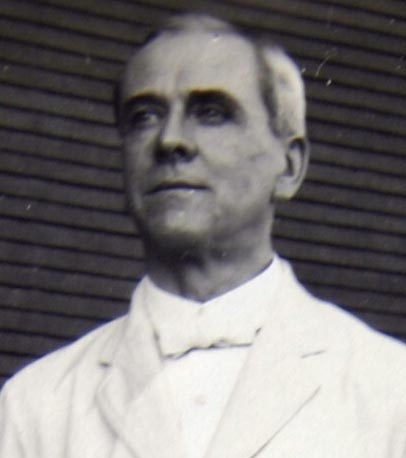

The Roundeye doctor, Mei Weiliang, or Dr. William Scott Ament, spoke the language of birds. An assistant translated. “Do you remember the English words the doctor taught you?”

Wu Yuan nodded. “English letter.”

“Very good. You are our last hope, Wu Yuan. Good luck, and Godspeed.”

The large doctor needled Wu Yuan’s shoulder fiercely, demon eyes burning with a ghost’s greenish light. An earlier messenger had attempted a different route by slipping through the barricades. He failed. Boxers were attentive, and everywhere, which did not bode well for Wu Yuan.

“Three days ago a native messenger, bearing our tidings, was sent out in fear and trembling, induced to attempt to reach Tientsin by lavish promises, and by the urgency of missionary entreaties,” a survivor of the Siege of the Legations, acclaimed author Putnam Weale, wrote in his 1900 book Indiscreet Letters from Peking. “But instead of even getting out of the city, the messenger was captured, beaten, and detained for several days…”

A most hideous capital punishment awaited those convicted of betraying their country: the lingchi death, or death by a thousand cuts.

Wu Yuan’s knees turned rubbery one foot off the wall, and he looked behind him. Past rubble and barricades sprawled brightly lit streets. The Tang Dynasty Hanlin Academy was engulfed in flames, casting fiendish shadows across rooftops. Blood-red flags draped storefronts. Lanterns painted the streets crimson, illuminating frenzied Boxers by the hundreds, fists raised defiantly toward the Legation. Somewhere, closer to the Forbidden City, drums beat. Dungchen horns blared. Wu Yuan’s side of the barricades resembled hell. Here, amongst the ruins, darkness reigned. Not a soul stirred. Open fires were forbidden for fear of tireless snipers.

Wu Yuan wiped away a tear. Peking black dust, stirred by soldiers, camels, and ash, turned his sleeve grey. Having just recovered from another round of consumption, he was leaving no family behind. His mama and baba were beheaded in his hometown in Shantung for following the Western gods. Schoolmates at his mission school had been rounded up and taken away. As far as Wu Yuan knew, he was a lone survivor. Baba hid him in a dried-up well, where he saw nothing, but heard everything. Mama’s screams haunted his dreams.

After the Boxers left, he fled with neighbors to Peking, where they were all now huddled, separate, and disdained by the Roundeyes inside the Foreign Legation.

“Even in this matter of Chinese refugees the attitude of our foolish Legations is rather inexplicable,” Putnam Weale wrote of the Chinese trapped alongside foreigners inside Peking’s Foreign Legation. “Actually up to within a few days ago some of the Ministers were still resolutely refusing to entertain the idea that native Christians—men who have been estranged from their own countrymen and marked as pariahs because they have listened to the white man’s gospel—could be brought within the Legation area.”

“Even in this matter of Chinese refugees the attitude of our foolish Legations is rather inexplicable,” Putnam Weale wrote of the Chinese trapped alongside foreigners inside Peking’s Foreign Legation. “Actually up to within a few days ago some of the Ministers were still resolutely refusing to entertain the idea that native Christians—men who have been estranged from their own countrymen and marked as pariahs because they have listened to the white man’s gospel—could be brought within the Legation area.”

Wu Yuan could stand the noise, the dust, the screams, no longer. Terrible screams, chilling words, his countrymen directed at him.

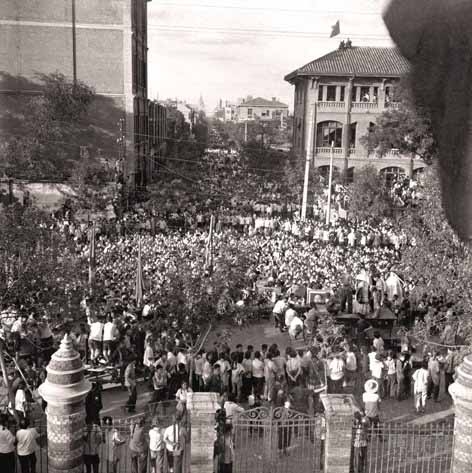

“They [Boxers] began shouting and roaring in chorus two single words, “Sha-shao,” kill and burn, in an ever-increasing crescendo,” Putnam Weale wrote. “I have heard a very big mass of Russian soldiery give a roar of welcome to the Czar some years ago, a roar which rose in a very extraordinary manner to the empyrean; but never have I heard such a blood-curdling volume of sound, such a vast bellowing as began then and there, and went on persistently, hour after hour, without ever a break, in a maddening sort of way which filled one with evil thoughts. Sometimes for a few moments the sound sank imperceptibly lower and lower and seemed making ready to stop. Then reinforced by fresh thousands of throats, doubtless wetted by copious drafts of samshu, it grew again suddenly, rising stronger and stronger, hoarser and hoarser, more insane and more possessed, until the tympanums of our ears were so tortured that they seemed fit to burst. Could walls and gates have fallen by mere will and throat power, ours of Peking would have clattered down Jericho-like. Our womenfolk were frozen with horror—the very sailors and marines muttered that this was not to be war, but an Inferno of Dante with fresh horrors. You could feel instinctively that if these men got in they would tear us from the scabbards of our limbs. It was pitch dark, too, and in the gloom the towers and battlements of the Tartar Wall loomed up so menacingly that they, too, seemed ready to fall in and crush us.”

Sleeping heel to nose, nose to heel, there was little room to breathe inside the Foreign Legation. Wu Yuan, standing no taller than a donkey’s back, perfect size for Knife-Sharpener Ma’s nightly farts aimed directly into his nose, rivaled the horror Wu Yuan had for musket fire and Boxer chants. Like rotten, thousand-year-old eggs.

Wu Yuan’s stomach grumbled. The porridge was bland, without salt, but still smelled delicious.

When Mei Weiliang the doctor asked for volunteers to send a message to Tientsin, 80 miles away, Wu Yuan raised his hand. He had nothing to lose. Suffering from consumption, he was already drawing near the wood. He didn’t need a fortune-teller to tell him how much longer he had. Better to die on the outside than trapped like a rat inside. They’d all suffered equally under the Boxers’ attacks, Roundeye and Chinese alike. Nearly a dozen Roundeyes and more Chinese than he could count were dead and buried in shallow graves. Food was scarce, eaten down to horseflesh, and a reward of 500 taels, approximately 350 Mexican dollars, was his upon completion of the mission. Five-hundred taels. A lifetime’s worth of noodles – with beef. Full stomach every day.

“Quickly, now.” The assistant said. “Before they see you.”

Wu Yuan sucked in his breath, clinging to the rope with both hands when the doctor pushed him over the edge. A ceramic crack rang loudly against stones below.

The doctor swore. The harsh sound curses make were also the same in any language.

“He dropped the bowl,” Ament’s assistant said. “It’s no good.”

Wu Yuan found his voice. “I’m all right. Let me down.”

Slowly, the rope lengthened. The doctor’s strange, hairy face grew smaller, then vanished within smoke. Wu Yuan found footing behind a massive stone, blown from the Tartar Wall. Imperial soldiers guarded the sluice gate not more than a hundred paces away. Both held torches. To the south where Tientsin lay, a road, usually teeming with merchants, camels, monks, and traveling troupes, was empty. Bodies strung from crosses, like the Western god’s Yesu, lined both sides.

Hands shaking, Wuyuan discovered the spilled porridge, and found the oiled silk message. He licked the secret message clean, then tied it around his ankle. Frayed pants hid the cloth. Although his heart beat faster than a hummingbird’s wings, he slipped from his hiding spot, shuffling slowly, as beggars do, straight toward the Imperial soldiers.

“Bless you, food please,” Wu Yuan said. He stretched his begrimed hands toward the nearest soldier. “A thousand blessing upon you. Food. Water.”

The Imperial soldier jumped in surprise. “Get away from here, you filthy beggar.”

Wu Yuan dropped to his knees. Held his hands over his head. “My family is dead. I’ve had nothing to eat for days. If you do not help me, nobody will.” Wu Yuan grunted when the soldier kicked his leg.

“Show some pity,” the second soldier said. “Can’t you see he’s starving? Even in times like these we cannot forget our Confucian principles.” A cold, metallic piece was pushed into his palm. “Now go. And if you know what’s good for you, you’ll stay far away from here.”

“Bless you. Thank you.” Wu Yuan bowed deeply, hugging the copper coin to his chest. Every instinct told him to run, but he bowed a second time. “I must get to my grandparents’ home in Tientsin. The journey is so long, I’m afraid I cannot make it.” He held up his hands again.

“Don’t take an inch to gain a mile.” The second soldier picked him up by his collar and tossed him toward the road. “Get going before I regret my charity.”

“Yes, thank you. Baba used to tell me the same thing. May the gods bless you.”

Wu Yuan turned his back on the soldiers, on the burning Tartar City, careful to keep the same, slow cadence. Sweat streaked his back. His lips shook with fright. He dared not glance at the dead, bodies poked like pins into the dusty earth. No more than a dozen steps away, Boxers, wildly screaming, carrying torches and spears – a thronging mass – crashed toward him. Wu Yuan edged to the road’s side, directly under the hanging bodies.

“Down with the foreign devils,” a Boxer screamed. “Kill them all, root and branch.”

Expecting he had been discovered, the ensuing chant chilled Wu Yuan to the bone.

“He heard the noise of guns and the roar of the mob who cried “Down with the Christians,” a 1920 book Rules of the Game by Floyd Wesley Lambertson said about Wu Yuan’s escape. “His eyes were blinded by the flare of torches and the glow from burning houses. There were dead bodies in the street. There were shrieks and groans. Everywhere, there were Boxer soldiers with guns or spears hunting for victims.”

But the first Boxer, dressed in black, red strips flailing from his wrists and ankles, passed him by. The second, a large man with a yellow charm pasted to his bare chest, only offered an uninterested glance. A third Boxer, dancing wildly, bumped his shoulder, sending him careening into an execution post.

Wu Yuan clung to the post, legs no longer able to move. His palms slickened. Toward the procession’s end, Wu Yuan recognized a young man, a former student at the same mission school he had attended, but had been excommunicated. Wu Yuan hung his head, and the man passed him by. Slowly, their vile chant diminished behind the Tartar Wall.

Wu Yuan waited for his heart to slow. Hours passed, it seemed. The Tartar City quieted. Even bulletproof Boxers needed sleep. A porridge vendor, pushing a groaning cart, idled past. Wu Yuan pried his fingers from the sticky post, and resumed his shuffle toward Tientsin, five paces behind the merchant, begging for porridge every other step.

Captured

Wu Yuan ambled south for two days, never walking quickly, for fear of being noticed, and always on the main road. Any other route would have been considered suspicious, and Wu Yuan wore his beggar face. He had nothing to hide. He slept when he could no longer walk, choosing places outside store fronts. In the open. Begged for food. Occasionally, he mingled with refugees from one village or another, until their route diverged. Most passersby offered him nothing but cursory glances, but a few, namely an elderly woman, handed him flat bread. A red-robed monk gave him a pat and an apple.

He woke each morning in sweaty pools, coughing, willing himself to forget the nightmares. The road to Tientsin was flat and dusty. Surrounding fields were desolate; crops were burned, and what tender shoots managed to escape the flames were blanketed by ash. The brown dirt was cracked, thirsty for rain. Wu Yuan stumbled upon a rain dancer, wearing a green wreath, and swinging a long, wooden sword. He watched the spectacle, fascinated. The grizzled man stabbed upwards and down, left and right, made whooshing noises and called upon the gods to send rain.

A dust storm came instead.

There were few hiding places along the way. Trees were rarities, under which he rested. He drank from algae-covered canals, clearing the grime before scooping up the bitter water. On the second night, his consumption flared, leaving him in a coughing haze. His stomach cramped. Dysentery wasn’t far behind.

Halfway to Tientsin, an empty, aching stomach forced Wu Yuan toward a village, which showed no signs of Boxers. With only a single copper piece, he ordered a bowl of noodles – without beef. He eyed the soup seller, chopping meat, enviously, but satiated his appetite with the thought that one day soon he could order all the beefy noodles his stomach could want. The fragrance was almost too much to bear, however, and he drooled as he slurped.

Sudden commotion stopped Wu Yuan midway through his noodles.

“They’re back,” the noodle man said. His face turned white. “Boxers.”

Boxers. A chopstick snapped in Wu Yuan’s hand.

A powerfully built man, queue snaked around a thick neck, bare chest covered in yellowed charms, marched into the village square. His underlings quickly ushered the inhabitants into a circle. Wu Yuan tried to flee, but Noodle Man kept him close.

“Stay close, child. Pretend I’m your father.”

“I have nothing to fear,” Wu Yuan said. A Boxer pulled Noodle Man into a male row. Women were separated as well, and stood shivering against a wall despite summer’s heat.

Great Elder Brother, the Boxers’ helmsman, inspected the villagers, took his time with the women, pulling two young ones away. Boxers turned clothes inside out, unwrapped bundles. An especially thin man found Wu Yuan’s half eaten noodles were still warm.

“And who are you?” Great Elder Brother stood before Wu Yuan. “Those were your noodles?”

Wu Yuan nodded.

“A boy of means. How fortuitous.” Great Elder Brother motioned for a Boxer to search Wu Yuan. A yellow-turbaned hunchback began rifling his clothing.

“You smell like a pigsty,” Yellow Turban said. The man’s face was wrinkled deep as the dry earth, and he walked as if he had a needle in his foot. Yellow Turban’s search moved to Wu Yuan’s legs. His ankle burned.

“Where is your home?” Great Elder Brother was growing impatient. Clearly, the Boxers weren’t finding any foreign devils or er maotzu, second-class long hairs, here.

“Shantung,” Wu Yuan said. “I’m on my way to Tientsin to find my grandparents. Roundeyes killed my entire family.” Mission school teachers taught lying was a sin, but in a situation like this, Wu Yuan guessed the gods wouldn’t mind.

Great Elder Brother cleared his throat, spat. “Stay with us. We’ll find some work for you.”

Yellow Turban finished patting him down. “He’s clean.”

“Thank you for your kindness, but I really must…” Yellow Turban pushed him toward the village’s main gate, where a line of young boys and girls was forming. Parents cried out behind him, calling out their children’s names.

“Line up.” Yellow Turban’s voice was high pitched, resembling a woman’s. He yanked the ears of two children, hauling them back in line.

“You should be thanking us, not whimpering like dogs,” Yellow Turban said. “You are all part of the ever victorious Harmonious and Righteous Fists. With us, you will learn to become fighters with iron waists, iron heads, iron bodies, impervious to bullets, resistant to water and fire. Study hard, be obedient, and you will be like the mighty Monkey King. Nothing will be able to penetrate you, not even the shells of the dog soldiers.”

“Now, for your first lesson. Repeat after me.” Yellow Bandit raised his hands, signaling the children to speak. “Righteous Harmony, we sacred Boxers, slaughter the foreigners to preserve our land. Boxers of Righteous Harmony, our power is great, indestructible.”

Wu Yuan did as he was told. Yellow Turban wasn’t satisfied.

“Louder.”

The children mumbled. A child nearest him received a slap. “Louder.”

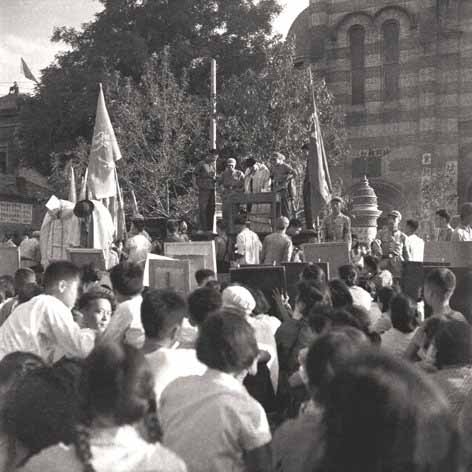

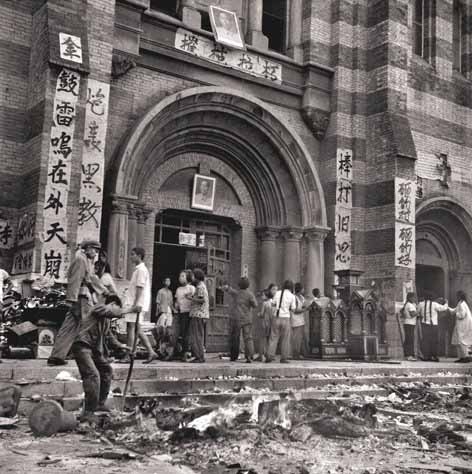

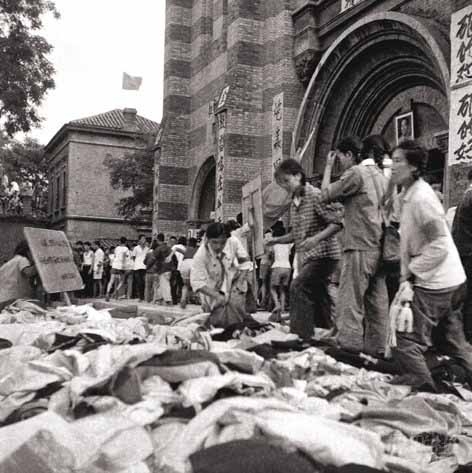

The exercise was interrupted when Great Elder Brother issued the order to move out. They marched south, toward Tientsin, but stopped at a smoldering village at sunset. Charred trees attested to the violence that had befallen the village. Bodies of men, women, and children were piled before the ruins of a Catholic church. Ravens cawed. Flies buzzed hungrily. Teary-eyed children swarmed like ants, hauling bricks from the wreckage, stacking them in neat rows. A hastily-built altar, brimming with flags, pouring incense from an urn on top, stood before the charred church’s entrance.

Yellow Bandit led Wu Yuan and the children to a tent. Three Catholic priests knelt in the dust, waiting death. Boxers with large swords lingered behind them, sipping tea. When Great Elder Brother arrived, the executioners snapped to attention.

“What are you waiting for?” Great Elder Brother said. “Send their dog souls to the eighteen hells.”

“Stay strong, brothers,” a priest said. “We dine in heaven tonight.” An executioner forced his head down.

The Catholic priests died quietly. One sword slice each separated head from body. Some might say the priests died bravely. But what good is bravery when it meets death? Fate, was the only real force in this world turned upside down. Fate had led Wu Yuan here, to this blistering village, and fate, perhaps, would see him through. When the heads fell, Boxers cheered. Great Elder Brother scowled. Apparently, he wanted a show.

An elderly man approached Wu Yuan, raised his arms up for inspection.

He showed his bicep. The old man, lean and swaying like a willow, frowned. After running in place and a dozen squats, Wu Yuan and one other child were found to be unacceptable for hard labor. They were pulled from the line; the rest were herded toward the bricks.

“Too weak,” the old man said. Wu Yuan collapsed when the old man gave him a shove. “Send this one to the inn. He’s strong enough to empty chamber pots.”

Released

Wu Yuan spent eight days cleaning chamber pots, hauling in fresh straw for bedding, and all the while his ankle burned with an urgency checked only by the deepening rattle in his chest. Consumption was returning with a fury. He weakened. The innkeeper, a lazy, toothless man, too fat to beat him, kicked him out when he coughed up blood.

“What should we do with this one?” Yellow Turban, more tanned and wrinkled than ever, hauled him into the Catholic church ruins, where Great Elder Brother lounged in an oversized chair. A Boxer altar had replaced the pulpit.

“What’s the matter with him?”

“He’s sick.”

“Homesick, more like it.” Great Elder Brother leaned close. Sniffed. Wu Yuan detected rice wine on the helmsman’s breath. He struggled to keep his chin up. “This one has a date with the paper man. Nothing we can do.”

The paper man. Wu Yuan had heard of the black magic. Legends said the paper man was sent up into the air by wu magicians, and fell heavy as lead, crushing its victims on whom it descended. He’d always laughed at the superstition, but the wild gleam in Great Elder Brother’s eyes, the way he sat back in his mahogany chair, judging him, turned rumor into truth.

Great Elder Brother tossed a silver coin in the air. “Go home. Enjoy a good meal before the paper man finds you.” A giant fist slapped into his palm. Wu Yuan bowed stiffly, and backed away, cringing at Great Elder Brother’s deep-throated guffaws.

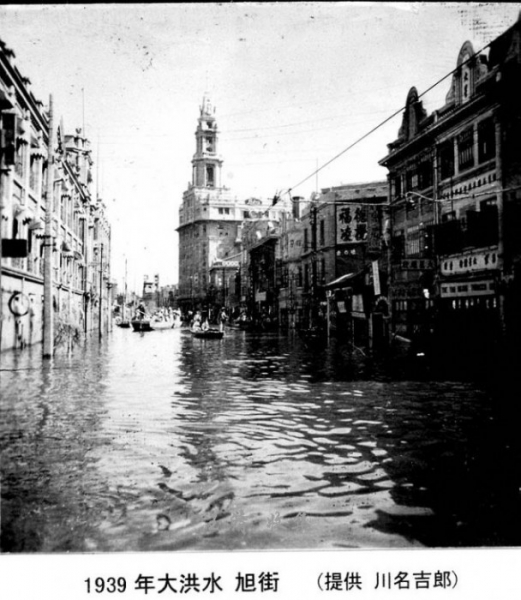

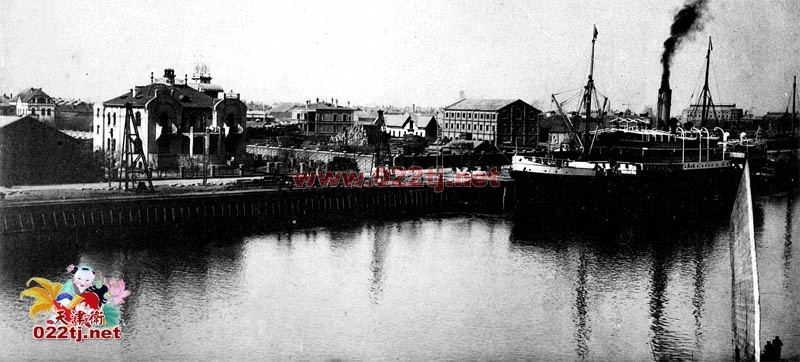

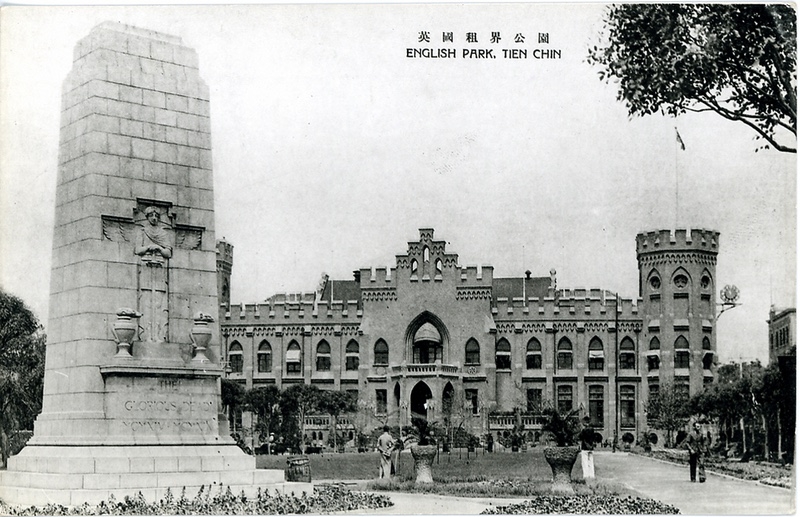

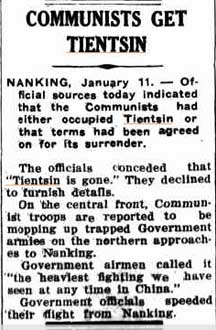

Tientsin

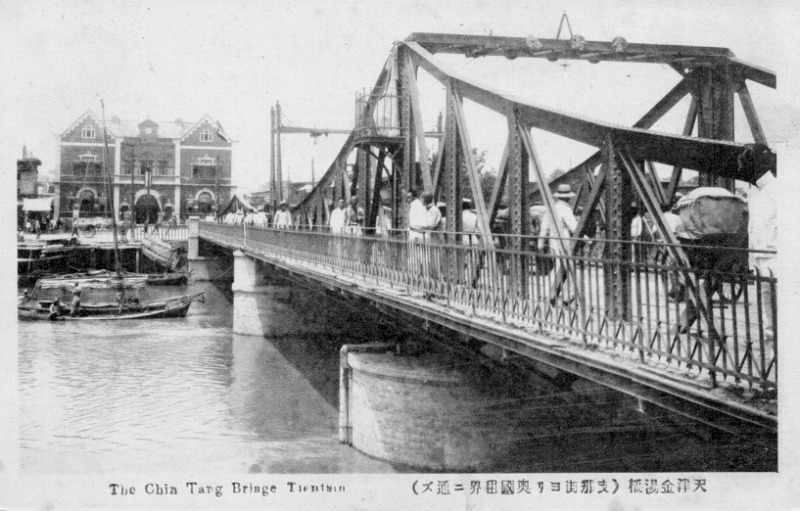

Noodles with donkey meat boosted Wu Yuan’s spirits, and he left the Boxer encampment with forty copper coins. His strength, however, diminished with each step, slowing his pace. Nearing nightfall, he came upon a boatman on the Grand Canal, spent most of his coins for a place to spend the night and passage to Tientsin.

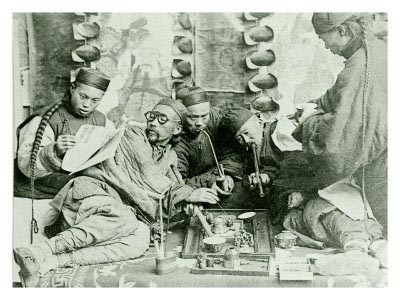

“I slept that night on a boat by the bank, and close by, on another boat, there was a Boxer altar,” Wu Yuan said in missionary reports written in China’s Book of Martyrs, published in 1903 and written by Luella Miner. “A crowd of Boxers, with wrists and ankles bound with red, and with red girdles, went onto the boat to worship their divinity, while others were practicing on the bank. Those practicing would first make obeisance toward the southeast; then, with cries like a hedgehog, they would brandish their weapons, or act dizzy and fall over backward. Others would lift them up and shake them, supporting them for a while; then they would strike out wildly in the air with their swords, leaping like madmen.

“I stood quietly watching them, not acting the least afraid, so they did not suspect me. They asked question of all on the boats whom they suspected, but asked me nothing.”

Next morning, when Wu Yuan awoke in another sweaty pool, the boatman was fleeing.

“Boatman,” Wu Yuan said. “Where are you going?”

“It’s too dangerous in Tientsin,” the boatman said. “Pleasure doing business with you.” He jingled a small purse, then disappeared over the bank.

“Turtle’s egg,” Wu Yuan said. Then glanced over his shoulder, half expecting the mission school teacher to be waiting with a ruler.

“There was nothing to do, but to start on again a’foot, going that day eighteen miles to Anping,” Wu Yuan said in China’s Book of Martyrs. “I met throngs of Boxers on the Great Road, all saying they had been summoned to Peking. As I always looked fearless and unconcerned, they paid no attention to me.”

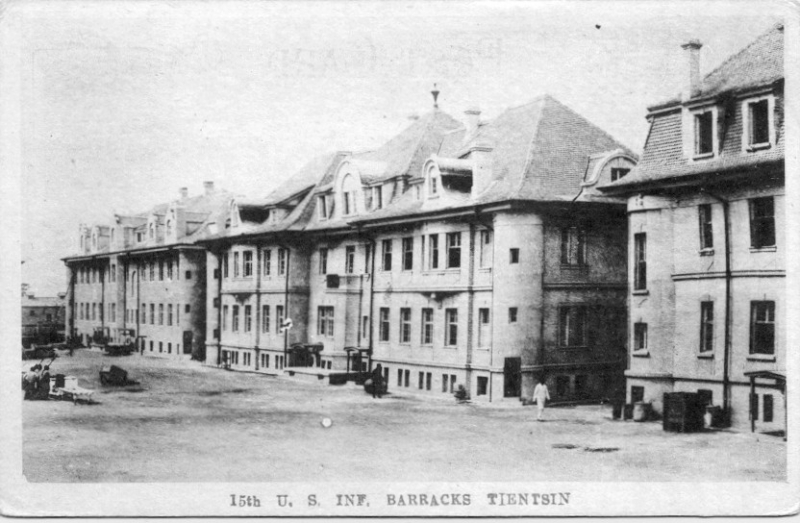

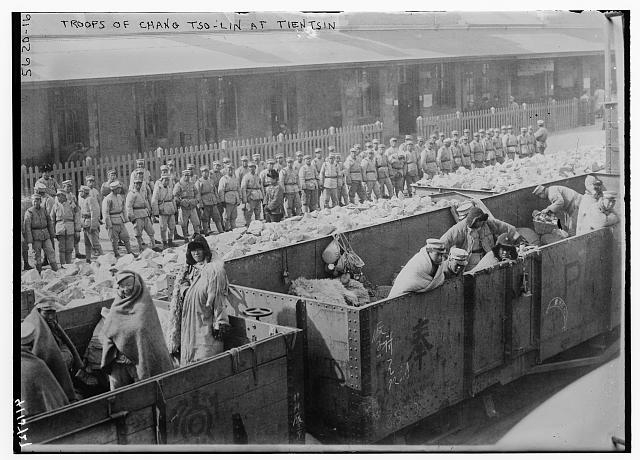

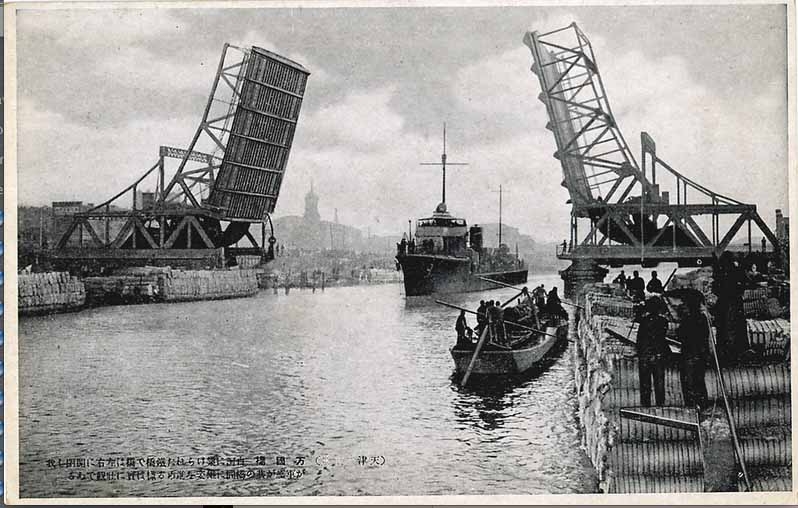

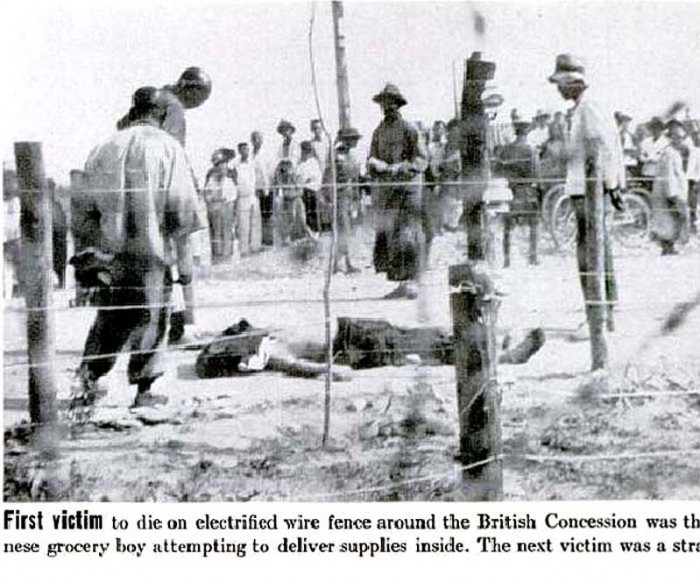

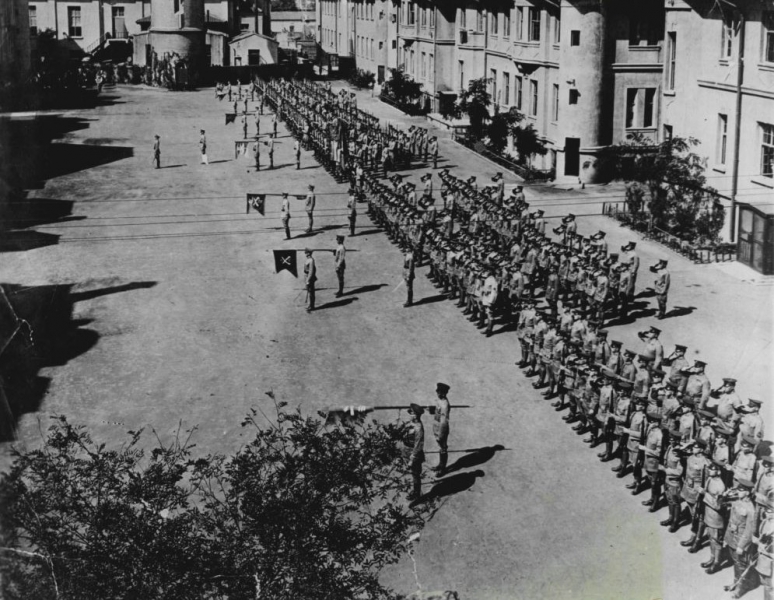

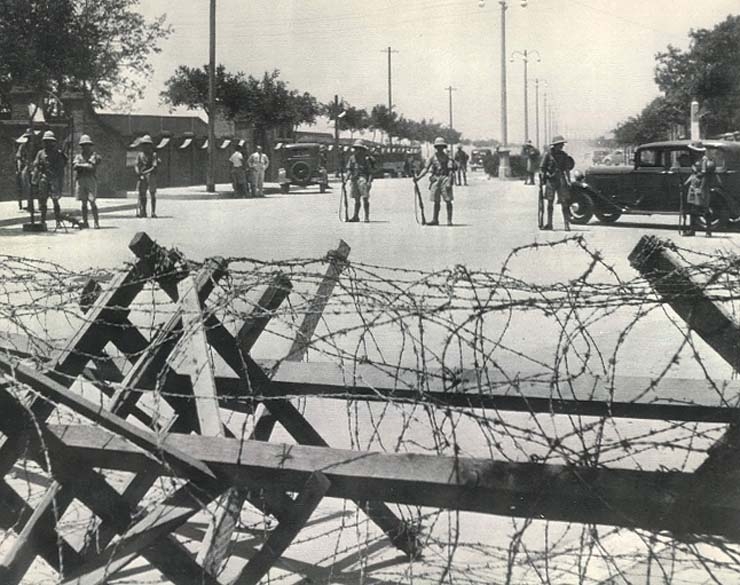

Despite his sickly condition, Wu Yuan traveled four more days, reaching Tientsin’s West Arsenal by June 27, 1900, according to the China Book of Martyrs. The Peiho’s eastern bank was strewn with dead Imperial soldiers and Boxers. Barricades were everywhere, and carefully guarded by Boxers. Day and night, lamps burned in every house. No one dared venture into alleyways. He found a place to sleep outside a shop by the Celestial City, two miles away from the Tientsin’s Foreign Settlement.

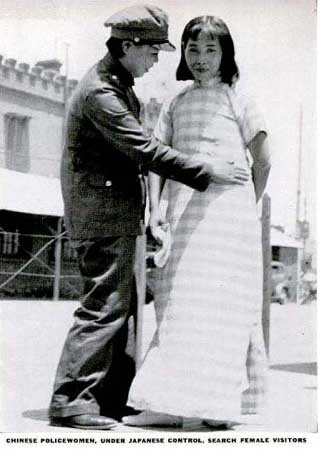

On the fifth day, Wu Yuan attempted to breach the barricades, but found all routes impossible. Being without money, exhausted, stomach cramping from dysentery, he found work keeping the camp registry for a Boxer army camped near Tientsin’s Mud Wall, near Taku Road. Chinese cannons blasted the Settlement constantly.

“I was greatly distressed because I could get no opportunity to steal into the Settlement with my message; but sad though I was, I never dared to show it. I saw that, even if I succeeded in getting into the Settlement, they were not in a condition to send soldiers to the relief of Peking.”

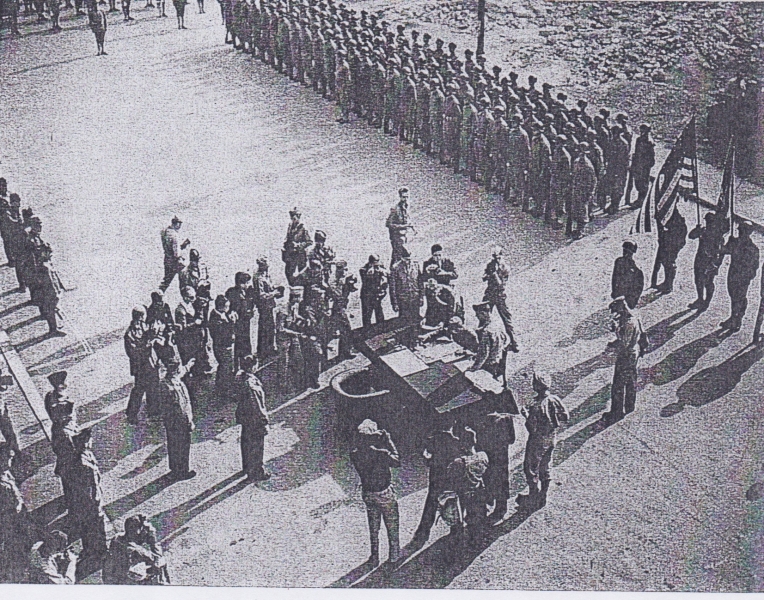

Corpses floated along the Peiho, collecting in the river dips, and creating an omnipresent stench. He worked with the Boxers until July 14, when foreign soldiers counterattacked, sparking the invasion, and eventual complete destruction of the Celestial City.

Corpses floated along the Peiho, collecting in the river dips, and creating an omnipresent stench. He worked with the Boxers until July 14, when foreign soldiers counterattacked, sparking the invasion, and eventual complete destruction of the Celestial City.

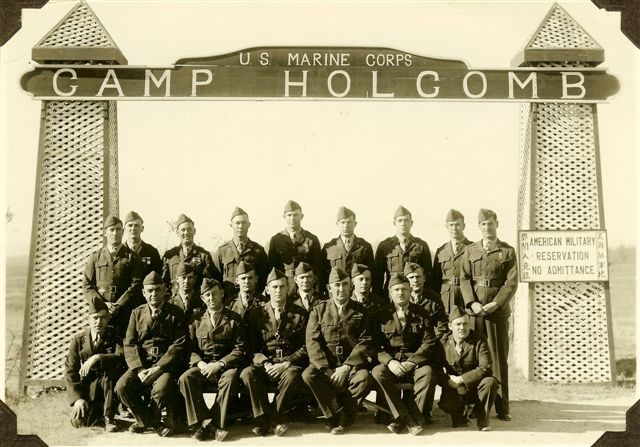

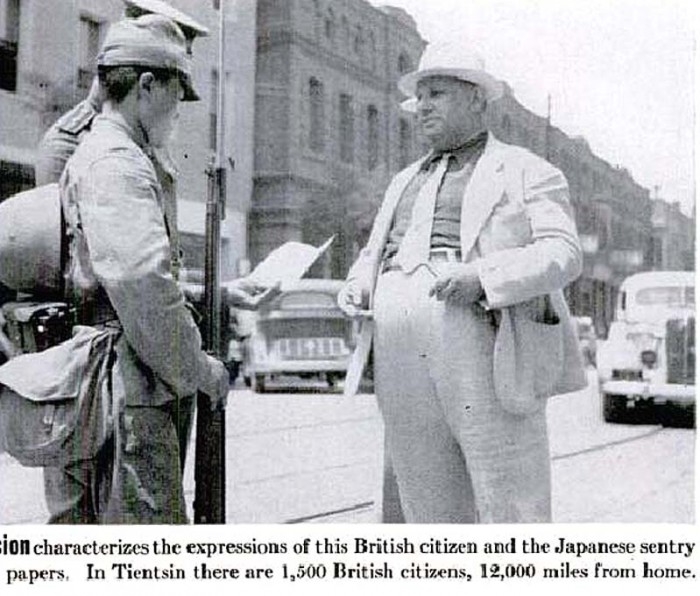

“I resolved to take in my letter at once, though I expected no reward, having delayed so long. I crossed the river, and went toward the north gate of Tientsin. All the others on the road were going northward; I alone went toward the city. I found the north gate open, and an English sentry on guard, who pointed his rifle at me.”

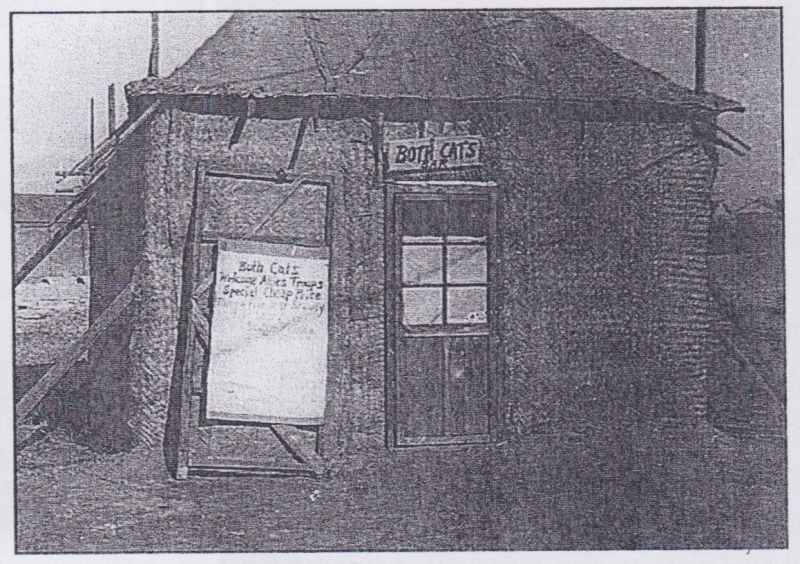

Wu Yuan quickly procured the message, waving it above his head. “English letter. English letter.” The English words, bird language, worked. The sentry led him to a small encampment where soldiers were eating breakfast. Beef, not horsemeat, wafted heavy in the air. The sentry perused his secret message, while a Chinese soldier in an English blue jacket uniform sauntered over. “Have you eaten breakfast?”

“No,” Wu Yuan said. “But I’m not hungry. My foreign friends are shut up in Peking, and are in great danger.”

“Not to worry,” the soldier said. “Don’t you know we’ve won? Eat something first, and then we’ll take you to the general.”

Wu Yuan wolfed down steamed rice and salted beef. The best meal he’d had since before Boxers slaughtered his parents.

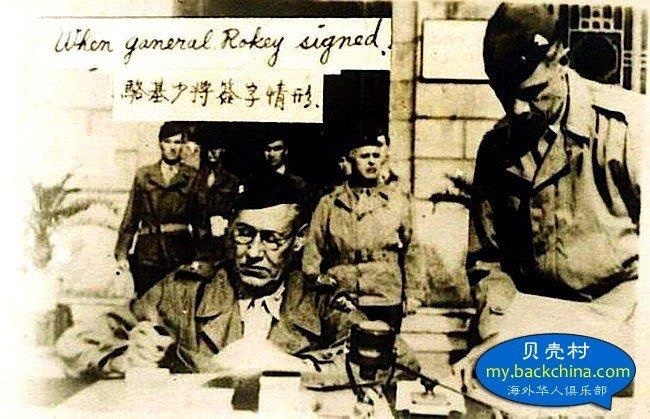

According to the China Book of Martyrs, General Sir Edmund Barrows received Wu Yuan. “Send help quickly,” the secret note said, according to the Rules of the Game.

“He took the letter, glanced at it, and then, as he was able to talk Chinese, he asked me several questions about the Chinese soldiers, whether they were scattering, and in what direction they were going,” Wu Yuan said. “He then took me to the British Consulate in the Settlement, here, Mr. Drew of the Customs, told me that he was ready to give me 500 taels as a reward for bringing the letter.”

Peking

General Barrows asked him to return to Peking with a half-inch-sized note hidden inside his collar. Traveling by foot, Wu Yuan left the next day. Bolstered by success, new provisions, clean water, and with few Boxers left on the road, Wu Yuan traveled 37 miles the first day. He slept in a destroyed locomotive. He was searched more than once by soldiers, who never discovered the secret note. Rumors that the besieged foreigners in Peking were overwhelmed, Wu Yuan no longer acted the beggar, but pushed as fast as his legs would carry him. Within four days, Wu Yuan reached Peking’s Tartar Wall, but was turned away at the Hata Gate. He entered through the Shun-chih Gate, guarded by red-turbaned Boxers.

“The next day, from early morning until late afternoon, he went hither and thither trying to steal through the Boxer lines. At last, he succeeded, and after several narrow escapes as he made his way toward the legations in the darkness, he reached a bridge on Legation Street held by American soldiers. There, he waited until light, when he was seen by a soldier.”

“Don’t shoot.” Wu Yuan forgot the foreigner most likely spoke no Chinese. “English letter, English letter.”

The soldier helped him up a bank and into the American Legation, then to the British Legation, where Wu Yuan revealed the missive, A vast army gathering in Tientsin will soon march to the relief of Peking, the note read.

“A curious figure this messenger bringing news from the outside world made as he sat calmly fanning himself with the stoicism of his race,” Putnam Weale wrote about Wu Yuan in the Indiscreet Letters from Peking. “I wish you could have heard him; it seemed to me at once a message and a sermon, a sermon for those who are so afraid. The little pictures this boy dropped out in jerks showed us that there were worse terrors than being sealed in by brickwork.”

The China Book of Martyrs recalled Wu Yuan’s arrival with the news as a godsend. “A glad crowd surrounded the little Chinese hero, and many eyes were dimmed with tears; but he seemed all unconscious of having done a noble deed. He had but done his duty, and was happy in the thought that he had done his foreign friends a service.”

Wu Yuan wasn’t the first messenger to bring good news. Shortly before Wu Yuan found his way back to the besieged foreigners inside the Tartar City, a Japanese messenger delivered the same news. But the arrival of a second messenger, and a note written by an English hand, confirmed the fact that help was on the way.

Putnam Weale further wrote about Wu Yuan in the Indiscreet Letters from Peking, although did not reveal the boy’s name. “Once he was tied up and made to work for days at a village inn. Then he escaped at night, and went on quickly, traveling by night across the fields. Somehow, by stealing food, he finally reached Tientsin. The native city was full of Chinese troops and armed Boxers; beyond were Europeans. There was nothing but fighting and disorder and a firing of big guns. By moving slowly he had broken into the country again, and gained an outpost of European troops, who captured him and took him into the camps. Then he had delivered his message and received the one he had brought back.

“That is all; it had taken twenty-four days.”

Wu Yuan lived two years after his epic journey, but consumption claimed his life early. He received the promised 500 taels, approximately USD 350, of which 200 taels went to help those suffering from his same disease, according to the China Book of Martyrs. A medal from the British Government testifying to the value of Wu Yuan’s services reached his friends soon after his death, and was encased in glass in the Museum of North China College, according to the China Book of Martyrs.