By C.S. Hagen

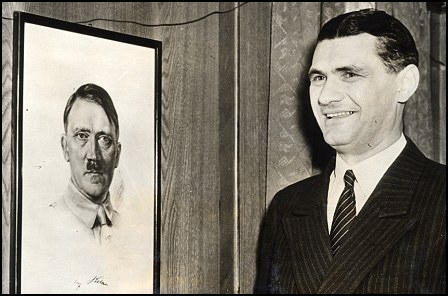

JAMESTOWN – A local news broadcast finished with a clip of US presidential nominee Donald Trump standing before a giant NRA poster. The 2016 Republican candidate gripped a podium’s sides tightly, raised a bushy eyebrow before promising to bring back the American dream.

Lore Hornung set her liverwurst on rye down, and pointed excitedly at the television set.

“The names we had for Hitler are like what we have for Trump,” Hornung said. “Names that I won’t repeat.”

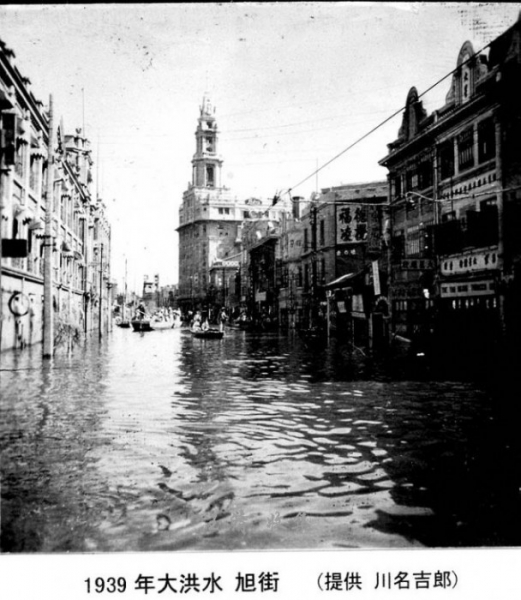

Born in Bad Rappenau, Nazi’s Germany, the 84-year-old woman recalled the day Adolf Hitler declared war on Czechoslovakia in 1939. Huddled around the “people’s receiver” radio with her four siblings and parents, Hitler’s rhetoric then reminds her of Trump’s promises today to make a country great again.

“The hateful rhetoric is what is frightening,” she said. “At first we thought Hitler was a clown, and then he became real.”

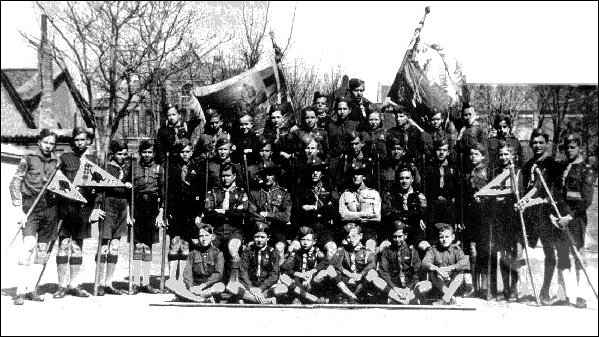

Using words like fear, self-protection, power, national pride interchangeably with broken dreams, Hitler stirred a nation to hatred. At only 10-years-old when World War II began, Hornung had no choice but to don the navy blue dress, white shirt and necktie, and the brown Hitler jacket emblazoned with the Nazi badge. The only gifts she says she ever saw from the Nazi regime.

“We had a good life before the war and could even afford a maid and a cleaning lady,” Hornung said. The day after Hitler’s declaration of war against Czechoslovakia, her father, a railway freight manager, fanned local stores hunting salamis and storable foodstuffs. “I was 10-years-old when the war began, and for the first six months everything was quiet.”

And then the changes began.

Shoes became a luxury item, one new pair every two years. “You would be lucky if you got one pair of shoes a year.” Additionally, new clothes disappeared from store racks. Many goods, including coffee and chocolates, required ration tickets, which were issued by the government. At her young age, she received a small box of chocolates, also government issued, at Christmas. Older children received real coffee, a welcome break from the muckefuk kaffee, roasted corn and chicory sweetened with beet sugar. “To this day I put no milk in my coffee, and no sugar in it,” Hornung said.

Stylish new clothes were impossible to find. International radio broadcasts were replaced by propaganda and speeches by Hitler and party propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, as the Nazi juggernaut conquered one sovereign nation after another.

The paramilitary wing of the Nazi party marched into town.

“First, they came in uniforms, brown shirts, and riding boots,” Hornung said. “My dad even had one. They came marching into town singing. It was so stupid.”

Young teachers were drafted to the frontlines. Older, stricter teachers wielding bamboo sticks for punishment replaced them. The school’s new headmaster was a fanatic, but mostly avoidable. He walked into school in the mornings with a Nazi salute. Living in a town of 2,500 people, a tourist spot for its brine hot springs, Hornung wasn’t subdued to the brainwashing techniques many other students her age in larger cities endured. Her years in the Hitler Youth, known as Jung Mädel for children up to 14, and later in the League of German Girls or the BDM, were spent primarily crafting wooden elves as Christmas presents, marching in formation on Sundays, listening to speeches, helping workers in the field, and singing nationalistic songs such as the Horst Wessel. Once a month her entire school of 18 students – four girls – watched a motion picture featuring German victories and the ever-present propaganda.

French prisoners, bedraggled and under guard, began appearing in town. Many were assigned day duties in the fields before returning to a nearby prisoner of war camp, she said.

One night, a nearby commotion piqued her interest. Her father rushed to discover what was happening. He returned with frightening news.

“I had never seen my dad so mad,” Hornung said. “And dad almost got into trouble. He said three Jewish families in town were attacked. Windows were smashed in, and rocks were thrown at them.”

In 1933, ten Jewish families lived in Bad Rappenau, according to the Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust. In 1938, four Jews were killed and a Jewish shop was destroyed in Bad Rappenau, according to the Jewish Cemetery Project. By October 22, 1940, no Jews remained; all were deported to the Gurs Concentration Camp in southwestern France, according to the Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust.

At a time when anything but mass conformity was persecuted, she wore a bikini to practice diving. “I was a tomboy,” she said. Chuckling at the memories, she said she used to climb cherry trees for a snack, stole away from Hitler Youth duties to swim. To Hornung, the Hitler fanaticism passed her by.

“Once I had made plans to swim,” she said. “Diving was my favorite sport. I could do flips even, but this night, my classmates tried to pressure me into going to help pick peas. I had already made my plans to go swimming, and I told them no.”

She was worried what her father would say, but his response surprised her.

“Never lie,” Hornung said her father told her. “Hitler says don’t lie, so you do not lie. If you made plans to go swimming, then you need to stick to those plans.”

Her father was a member of the national socialist party for the first year after war broke out, Hornung said. “For the first year or so my father supported them, and then he left the party and refused to wear his Nazi pin.”

When the Allies began bombing campaigns in Germany, Hornung and her sisters refused to leave the upstairs open window. They knew their small town of 2,500 would be of little interest to the invaders.

“We would open the window up and start counting how many airplanes. When they left we also counted, and sometimes as many as 60 or 70 were missing.” Her father would encourage them to go downstairs into the basement for safety, but usually end up watching the spectacle with them, Hornung said.

Her town was hit once by Allied bombs, forcing her and her family to spend the night in their basement. Little damage was caused however, but she worried, as everyone knew an armaments factory was nearby. The nearby city of Heilbronn, however; was devastated by bombing raids. On September 10, 1944 Allies dropped 1,168 bombs on the city, killing 281 residents, according to the World War 2 Database. Within one half hour on December 4, 1944, more than 6,500 residents died during a second bombing raid, most of whom were buried in mass graves, according to the World War 2 Database.

The Americans invaded Hornung’s town first, she said. From her kitchen window she watched as a tank parked into her front yard. A large man asked for English speakers, of which she was one.

“He asked me if there were any German soldiers, and I said no,” Hornung said. “Then he filled his steel helmet with potatoes, and that just didn’t go well with me. I said ‘you potatoes, me meat.’ And then he spoke a lot of English I didn’t understand and took me toward another tank. I thought, ‘Oh no, they are going to take me away,’ but he gave me a large tin of ham.

Once, while riding her bike she came across chickens, and in her hurry to stop her chain broke. She crashed in front of a group of US soldiers.

“I was so afraid they were going to hit me for running over a chicken,” she said. “I was afraid the Americans would kill me, but instead they helped bandage my scuffed arm. They were good to us.”

The tomboy in Hornung refused to let the US soldiers have free reign with local swimming pools, which, according to Hornung, became property of the US Army and local residents were not permitted to swim. She defied the rule, however, and went swimming anyway.

“I said come and get me, and he did not. Maybe he couldn’t swim, I don’t know.”

German surrender on May 7, 1945 brought inflation, a scarcity of food, and horrid revelations to Hornung. She and her family had no idea of how Jews had been treated across Europe. “We did not know about it, not until the newspapers began reporting on it and then we saw the people coming in. Some of them walked for two weeks surviving on what farmers fed them.”

“We were so glad when it was over, we hardly kept anything to remember those days,” Hornung said. “I did not live in a big city, just in my hometown with two thousand or so people.” The majority of Germans in her area shared her relief, Hornung said. “But there were some then who were like those today crazy about some politicians,” she said. Small gangs formed. Some took advantage of the lack of a functioning government, looting and robbing. Devastation in nearby Heilbronn, was difficult to imagine, she said.

Hornung and her mother, a Swiss national, escaped some of the post war hardships by traveling to Switzerland, and did not return until they heard father was seriously ill. He died soon after they returned home. Nearly seven years after the war ended, Heilbronn still resembled a war zone.

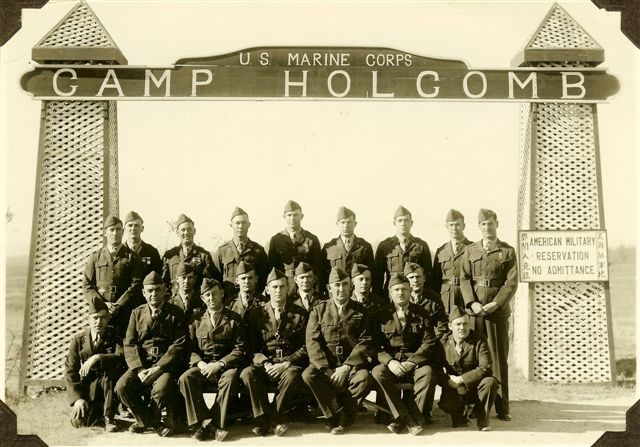

She met her future husband, Jamestown native Staff Sergeant Glen W. Hornung, at Café Mayer, in 1952. “A most beautiful café,” Hornung said. At the time Glen was sent to West Germany as a Jeep mechanic.

“It was all rubble,” Glen, who was a private when he set foot in Germany, said. “The houses were bombed out, streets were full of rubble ten-feet high. People had nothing to work with.” He too was a self-admitted ‘outlaw,’ and spent his first years in the military drinking, and chased Hornung for nearly two-and-a-half years before she agreed to marry him.

“I lost more stripes then than most people ever make,” Glen said. After a night with bad Thai whiskey however, he decided the drinking must end, and has never taken another sip of alcohol since. The gangs, or “local yokels,” as Glen described them, frequently created mischief. Fistfights with them were common, he remembered.

The Hornungs boarded the USS Upshaw from Bremen to New York City in 1956. From there, they moved their family around the world until eventually resettling into Glen’s hometown, Jamestown, not far from where his German ancestors, immigrants of more than a century ago, homesteaded.

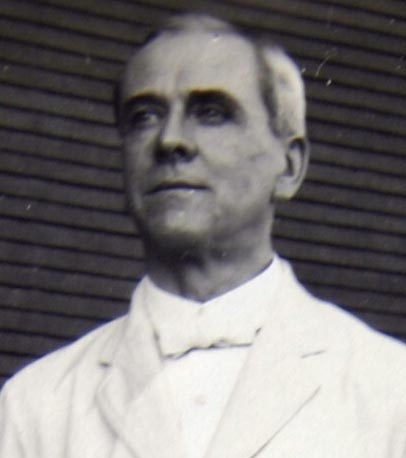

Lore Hornung, German born survivor of Nazi Germany, and her husband Staff Sergeant Glen W. Hornung, in their Jamestown home. – photo by C.S. Hagen