Looking back 154 years, little has changed in the Peace Garden State

By C.S. Hagen

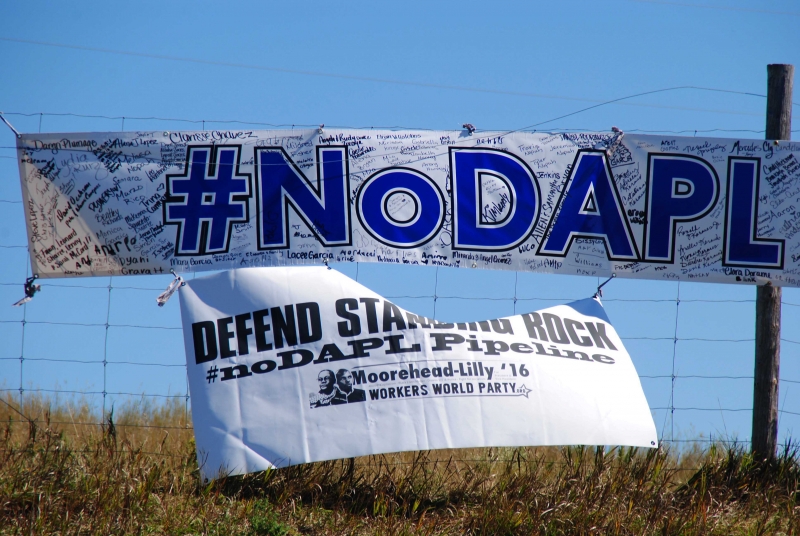

BISMARCK – The same prejudices that sent 38 Dakota Native Americans to the gallows in Minnesota 154 years ago still exist in the Peace Garden State today. Parallels between the broken treaties that sparked the six-week US-Dakota War of 1862 and the current fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline contain undeniable similarities, red man and white man say.

Standing Rock Sioux Chairman Dave Archambault II has repeatedly stated the Sioux tribe is not only fighting water and land rights, but also defying hundreds of years of broken treaties and oppression.

Little has changed since the day after Christmas 1862, the day of the U.S. largest mass execution in Mankato, Minnesota.

“The overt racism that exists here in North Dakota is something that shocked me,” retired rancher and former candidate for the North Dakota House of Representative Tom Asbridge said. His family has lived in or near Morton County since the late 19th century. “It is North Dakota nice. During holiday times we pride ourselves for handing out turkeys to poor kids, but the rest of the year we ignore what is going on. There’s a lot of self-delusion here about who we are, and people who are smart prey upon that. We shouldn’t blame them, but blame the people who are too dumb to know the difference.”

Bismarck native and wet plate artist Shane Balkowitsch decided to commemorate the 154th anniversary of the Dakota 38’s mass execution with a wet plate featuring renowned flute player and writer Darren Thompson.

“I made this wet plate in the historic wet plate collodion process to remember and pay respect to the 38 Native Americans that we executed a day after Christmas in 1862 by Abraham Lincoln,” Balkowitsch said. “The oil dripping down the rope symbolizes the current protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Have we learned nothing from past historical tragedies?”

Thompson, the subject in the wet plate, is an award-winning flute player and a journalist who lives in Rapid City, South Dakota.

Growing up on the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Reservation in Northern Wisconsin, he didn’t hear about the Dakota 38 until later in life. The story upset him, and he recently stepped from behind his role as a journalist to help Balkowitsch with his wet plate “Death by Oil.”

“It was difficult because originally I was planning on covering it as a journalist, and not being in the photo,” Thompson said. “It was difficult especially in terms of how can I explain this story.

“But he said ‘you have a voice that I don’t have, you can make this image reach to larger masses of people than I could.’ It would be a modern look of a Native American man.”

The Dakota 38: “It is a good day to die.”

Little by little, through trick and by trade, the federal government ate away at Dakota lands in southern Minnesota. Starting in 1805, the nomadic Dakota people were forced into smaller and smaller areas surrounding the Minnesota River, according to the Minnesota Historical Society.

In 1819, the US Army began building forts, settlers soon followed. Animals the Dakota depended upon for survival vanished from the forests. Missionaries promised education and farming assistance. Politicians threatened reprisals if treaties weren’t signed. Eventually, 35 million acres were exchanged for a promised USD 3 million, which the Dakota never received in full. Despite disagreements within the Dakota tribe, treaties were signed, but the translations were false.

The Dakota were tricked, lost half their land, and now owed fur traders in excess of USD 400,000. Those that refused to change their ways were threatened with more reprisals, and were not allowed to return to their homes. Annuity payments were late.

In 1862, the Dakota had enough. War began.

Settlers in Renville County lived opposite the Dakota, three days after the attacks began the county was abandoned, as most had been killed, wounded, captured, or had fled, the Minnesota Historical Society reported. The attacks took settlers by surprise. Those that escaped fled to Fort Ridgely.

General Henry Sibley led the U.S. Army against the Dakota. Sibley was no Indian hater; he spoke the Dakota language, and was well acquainted with the four tribes, according to historian William Folwell.

He was frequently opposed by General John Pope, who subscribed to a Three-Alls policy: kill all, burn all, loot all. Sibley resisted.

“It is my purpose utterly to exterminate the Sioux if I have the power to do so and even if it requires a campaign lasting the whole of next year,” Pope wrote to Sibley in 1862. “Destroy everything belonging to them and force them out to the plains, unless, as I suggest, you can capture them. They are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made.”

The campaign against the Native Americans ended at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. Dakota warriors lay in ambush against Sibley’s forces near Lone Tree Lake, while soldiers broke camp. They attacked as Sibley’s forces marched. Sibley won the battle, but not without casualties to both sides: seven white soldiers were killed, 33 wounded, 15 Dakota, including chiefs Makato and Mazamani, were killed.

A total of 152 civilians were killed, 48 soldiers or militia killed, 113 settlers and soldiers were captured, and 201 people escaped, according to some estimates. Other historians report more than 600 people were killed in total. Only 24 percent of the survivors returned to Renville County after the war.

The numbers of Dakota killed during the war estimate from 75 to 100, and by some reports much higher, but more than a fourth of the Dakota people who surrendered in 1862 died the following year. More than 1,000 Dakota were captured, and were forced into concentration camps on reservations, pressured to assimilate, and their lands were taken by white settlers, according to the Minnesota Historical Society. Eventually, all Dakota were forced from Minnesota; all treaties were destroyed. Many fled to North Dakota and Nebraska.

The U.S. Military Commission convened at Camp Release to try 392 Dakota prisoners. Proof of crimes was difficult to obtain as President Abraham Lincoln’s criteria for capital punishment was to sort out those who had committed rape and murder from those who participated in battles.

The trials were known as a mockery, both blind and ignorant, according to the Family and Friends of Dakota Uprising Victims. Language barriers, lack of proper translations, and local hatred against the Dakota spurred judges to quick determinations. A total of 303 people were originally sentenced to death, and 16 were given prison terms. President Lincoln shortened the list to be executed to 39, and one elderly man was spared minutes before the execution by Sibley.

Under orders from President Lincoln, the U.S. Army carried out the largest mass execution in U.S. history in Mankato, the word for Blue Earth in the Dakota language.

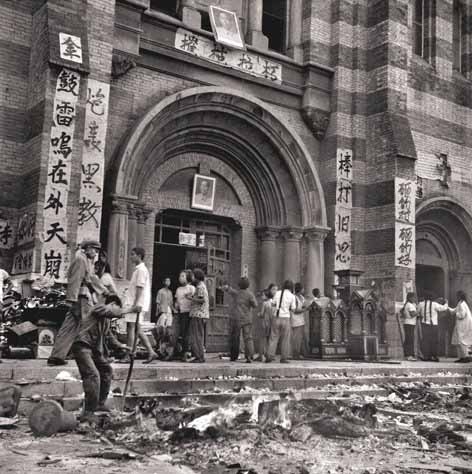

The day before the mass execution, Reverend Stephen Riggs said some of the condemned “availed themselves of the opportunity to receive the Christian rite” of baptism. The prisoners were chained in pairs and to the floor.

“It was a sad, a sickening sight, to see that group of miserable dirty savages, chained to the floor, and awaiting the apparent unconcern the terrible fate toward which they were then so rapidly approaching,” Riggs wrote for newspapers in 1862.

A man identified as Father Augustine Ravoux, a noted Catholic patriarch of the Minnesota church, addressed the condemned, but was interrupted when an elderly Dakota “broke out in a most lamentable and unearthly wail; one by one took up the lay, and ere long the walls resounded with the mournful ‘death song.’”

When a second missionary began his address, the Dakota once again began singing.

Soon after, the condemned were bound, hands behind their backs. Many dressed in traditional blankets, white muslin hoods were slipped over their heads.

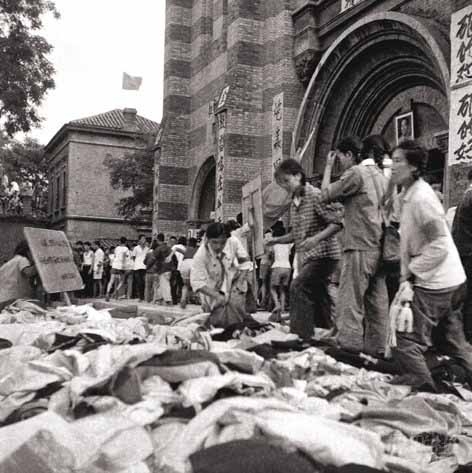

At precisely 10 a.m., the condemned were then marched to the gallows, a square structure on Main Street, between the jail and the Minnesota River. “The mechanism of the whole thing consisted in raking the platform by means of the pulley, and then making the rope fast, when by a blow from an ax by a man standing in the centre of the square, the platform falls; the large opening in its centre protects the executioner from being crushed by the fall.”

They wore war paint, and hopped on one foot to the gallows. Some of the condemned who had been “Christianized” sang “I’m on the Iron Road to the Spirit Land,” while others sang a native war song. One person among the condemned yelled out, “Hear me my people, today is not a day of defeat, it is a day of victory. For we have made our peace with our creator, and now go to be with him forever… Do not mourn for us, rejoice with us, for it is a good day to die.”

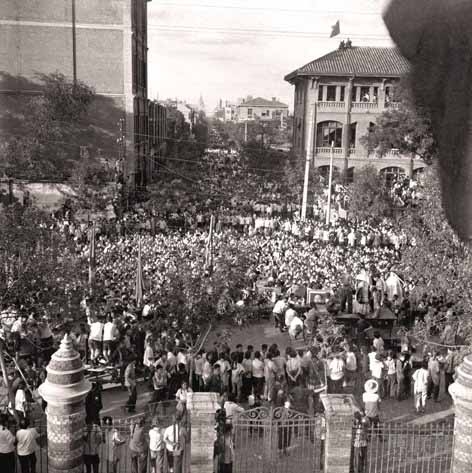

The spectacle drew people by the thousands. “Every convenient place from which to view the tragic scene was soon appropriated. The street was full, the house tops were literally crowded, and every available space was occupied.”

More than 1,500 soldiers also were present to keep the peace.

“Instead of shrinking or resistance, all were ready, and even seemed eager to meet their fate. Rudely they jostled against each other, as they rushed from the doorway, ran the gauntlet of the troops, and clambered up the steps to the treacherous drop. As they came up and reached the platform, they filed right and left, and each one took his position as though they had rehearsed the programme.”

Three taps of the drum signaled the executioner.

Upon the first tap, the condemned reached for each others’ hands, and shouted out their names to watching relatives.

The second tap followed. Stillness descended upon the scene.

“Again the doleful tap breaks on the stillness of the scene. Click! Goes the sharp ax, and the descending platform leaves the bodies of thirty-eight human beings dangling in the air.”

Most died instantly; some struggled. One rope broke, and a new length was quickly tied and the condemned hung until he was dead.

“Thirty-eight human beings suspended in the air, on the bank of the beautiful Minnesota; above, the smiling, clear, blue sky; beneath and around, the silent thousands, hushed to a deathly silence by the chilling scene before them, while the bayonets bristling in the sunlight added to the importance of the occasion.”

Their bodies were buried in a large hole in a sandbar in the Minnesota River.

President Lincoln later explained the mass execution to the U.S. Senate.

“Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.”

Many local politicians and military personnel sent telegrams to the President to execute all 303 prisoners.

Sibley sent a telegram to President Lincoln the day after the executions. “The 38 Indians and half-breeds ordered by you for execution were hung yesterday at 10 a.m. Everything went off quietly.”

Racism today

Thompson began teaching himself the flute while in college and now tells native stories with his songs, frequently in the Black Hills at the Crazy Horse Memorial, the world’s largest stone carving, which is not yet finished. Many of his tribe’s old songs and traditions are gone, but he’s discovered a few songs Jesuit priests recorded years ago, and he creates his own music.

He plays prayer songs, songs for nature, songs to honor corn grinding, which he described as experiences for people to be baby fed native trauma and culture. Before Europeans “discovered” America, estimates put 50 million natives north of the Mexican border. By 1900, less than 100,000 remained, he said.

“With that comes an immeasurable loss of a people, languages, knowledge, their history, and their culture, and one of the ways I try to emphasize that particular fact is explaining this music is a part of who we are and it’s a very pleasant thing to listen to.”

Thompson has seen racism up close and it has been personal. As an Ojibwe, his tribe had issues over hunting and spear fishing rights, a fundamental part of their original treaties with the U.S. government. One of the ideologies he faced as a child was the “Save a walleye, kill an Indian” slogan. He has brown skin, and was called a “timber n*gger.” He received death threats in college, and close friends were also threatened.

The dangers Native Americans face today are just as real as they were in 1862, he said, although this time perhaps not at gunpoint, but with the burning of fossil fuels. Communication and mutual understanding could ease the months-long standoff.

“If somebody is wanting to understand, they need to specifically go in to speak with the people of Standing Rock,” he said. “It’s going to become too late if we don’t stop being so reliant on fossil fuels.

“What’s really challenging for an entire community is to have to swallow the inability of this company to consult, to invite the community to the table to have significant contributions. In the lack of doing that 86 burial sites were desecrated or harmed because of their inability to consult or to invite the community to the table.

“The people there are not anti-white, they’re anti-greed. They want a clean environment for everybody. It’s not that they want to harm the police or harm the pipeline workers. The people that want the pipeline want it built only because native people don’t want it built.”

Asbridge said racism is deep-rooted in the Peace Garden State, frequently reminding him of the days in the deep south when white people believed they had a moral right to go so far as to have white-only drinking fountains.

In coffee parlors and coffee shops around Bismarck he’s heard people say “we ought to go kill those damn Indians that are protesting.’

“Makes you wonder. When you hear it, it’s just really startling, do you really know what is coming out of your mouth? We’re being guided here without us thinking very clearly.”

Racism dates back to 1862 and beyond, Asbridge said.

“It’s kinda cultural, it goes back to the Scandinavian and the German roots – we got that built into us, instead of questioning government, we defer to it. An example is the response of police to the pipeline, they’ve been the aggressors in my mind, no question about it. I think they were sent there to antagonize the Natives.”

Early on, someone should have went down, rolled up their sleeves, and over pots of strong coffee discussed plans, man to man. “That to me is a crime, it’s a criminal activity to do that. The dogs, the rubber bullets, the water hoses, what the hell is the purpose of that?

“It’s an indicator of the culture here. Fighting the culture is a tough job.”

As Jack Dalrymple prepared to step down from the governorship, he received a standing ovation after he praised law enforcement and National Guard efforts during the Dakota Access Pipeline controversy. “Many of our people have gone months without a day off, ably managing the onslaught of out-of-state agitators in a situation that could never have been anticipated.

“The people of North Dakota can take satisfaction in knowing that the financial strength of their state is among the best in the nation,” Dalrymple said. He left a financially stable state to the newly elected 33rd governor, Doug Burgum.

The state may be financially secure, at least for the time being, but many agree the Peace Garden State’s spirit is sick. The symptoms are evident; the disease is contagious. From state politicians accepting big oil bribes during election races, to ignoring its first citizens, to not consulting appropriately with sovereign nations, to repressing the collective voices of North Dakota’s original peoples, racism is still alive and well, and living in the Peace Garden State.