Fargo resident travels to western China in search of one of the last known “fox demon” shamans in modern times

By C.S. Hagen

SHAANXI, CHINA (PRC) – Chen Xing yawned for the tenth time and moved to the screened door of his shaman clinic. He yawned not from boredom, but rather in preparation for the spirit about to possess him.

Among other more painful effects, the yawns were a human side effect and a small price to pay for signing a deal with a fox spirit, he said. Xing yawned once more, this time longer and louder than before.

“When it possesses me I don’t know or remember anything,” Xing, who prefers to be called by his new name, Chen Saiwa, said. His final yawn was an impossible, bone-chilling intake of breath that lasted longer than half a minute. His eyes burned like slow-burning coals and he smiled a second before the possession was complete. “It’s all through the Boluo Fox.”

At the screen door he doubled over, retching, and then stood. His slightly plump, young body no longer resembled the 37-year-old peasant’s son. Ask the villagers of Boluo or the infirmed in Yulin, Xi’an, or Inner Mongolia and he was Chen Saiwa, local shaman healer, diviner and messenger of Guanyin Pusa, or the Goddess of Mercy.

Eyes squinted and teary, only two front teeth protruded from between his pursed lips. Although the day was clear and sunlight streamed through a crack in the tinted, boarded-up windows, his thinning, dark hair had gone almost completely grey. Hands behind his back and slightly bent forward at the waist, his movements were stiff and slow, those of a much older man. He used yellow charm paper to wipe tears from his eyes.

“Good, good,” Saiwa said in a different, gravelly voice. Dressed in blue jeans, a wife beater T-shirt and tennis shoes, he scraped his feet to the fox altar that held two bottles of Chinese wine and snatched one of them. Saiwa thirstily swallowed once – as easily as the potent alcohol was water – then spat a second on his left palm holding it to the light for study.

“I am nothing but a small, small fox spirit. Hei-ki-ma-hei-ki-ma. What is it that you seek?”

Fated for Possession

Beneath the crumbling, baked brick walls of Boluo Castle in northern Shaanxi province an entire village believes in the Boluo Fox. They have believed since before World War II. They say a man named Lei Zheng Wu, known to villagers as Old Wu, was the spirit’s medium before he died of liver cancer in 1994 and Saiwa accepted the fox’s terms.

They call Saiwa and his progenitor miracle workers, healers of the sick of body and soul, and many smile warmly when asked about their local hero.

“At first, like many others, I didn’t believe,” said Wang Xinxin, a former resident of Boluo now living in nearby Yulin. “But Old Wu treated me for an illness and he treated me well. Later, Chen told me everything from my past very clearly, things he could not or should not have known. I thought Saiwa was crazy at the beginning, we all thought he was crazy, but now many people from Boluo even Inner Mongolia come here to Yulin to get healed.”

Both men’s stories are similar, Wang said. Before accepting the fox spirit, neither of the men could read nor write. Both were poor, Old Wu learning the trade of goat herding and Saiwa that of an underpaid chef.

“His food was terrible to eat,” Wang said.

And both men underwent three years of intense sickness.

“I am a peasant’s son,” Saiwa said. “I was completely opposed to it at first. But I couldn’t work, couldn’t make money. I was so sick and the hospitals had no idea why and could do nothing for me. For three years I went through a bitter time. The fox beat me down until I agreed, and since it possessed me I got better, day-by-day until now I can live a normal life.

Saiwa is married and has paid the government fines by having a second child. His predecessor Old Wu was married with seven children, six boys and one girl. He admitted he feels blessed with virility and wants more children.

“It spoke to me and told me then it was the Boluo Fox,” Saiwa said, “and that it was fate that we should be together.”

Old Wu and the First Possession

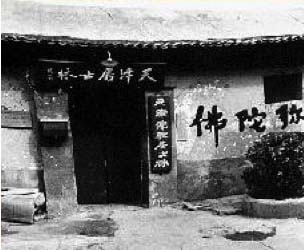

A fox shrine in Boluo stands behind the former home of Old Wu and is guarded religiously by his sons. On the southern side of the shrine there is a small house, an outdoor kitchen and a hollowed out cave where Old Wu used to heal and his grandfather once lived.

“This is the real clinic,” said Lei Ying, the eldest of Old Wu’s sons. He is the son of lightning, Ying joked, as the surname Lei means lightning in Chinese. Despite the rumors that the children of fox spirits are imbued with supernatural abilities, he says neither he nor his siblings are so blessed.

Legends that foxes are demigods of fertility stand to reason, he said. Ying is older than sixty and wears large sunglasses and a wide-brimmed straw hat. His handshake is strong and he brandishes a friendly smile at every question. He opened the doors to his childhood home and gave a tour of the inside of the small fox shrine. Six stone markers stand like graves toward the east side of the structure.

The white, stone shrine had no stairs going up and yet was three stories high. A small room at the bottom of the shrine was made for worshippers. Old Wu’s son lights four incense sticks inside the clinic, bows and talks of his childhood.

“It was strange growing up with a fox spirit for a father, but I could do nothing to change that,” he said and pointed to the drawing of his father at the altar. In the picture, a white turban is wrapped around his father’s head and he wears a Mao-styled jacket. The room is lined with red silk banners emblazoned with gold-colored writing in appreciation for Old Wu and Saiwa’s shamanist work. Even as a child, he said, neighbors or classmates did not ostracize him and his family, at least not until the Cultural Revolution.

“My father was reluctant at first. Before the fox spirit possessed him he could not read and the only thing he knew how to do was tend sheep.”

After three years of sickness where he wore little but undergarments in the winter and thick wool coats in the summer, the fox spirit possessed Old Wu, and he could not only cure the sick, he could read and write charms as well. All without any study, Ying said. He was capable of performing shamanistic rituals, read people’s fortunes and write charms to ward off evil. He began each session by spitting wine into his left hand and examining it, Ying said.

“It was as if the spirit gave him the powers to read and write, to predict the future and cure the ill.

“He used to sit in a chair here,” Ying pointed to a desk near the old door where a chair once stood. “And he kept his door open at all times. People would come by, they would lie on the bed and he would spit wine on to his hand and perform miracles.”

He charged an average of five Chinese dollars per visit, not a trifling fee before World War II, but never turned a patient away.

“I was healed here once as a boy,” said Zhang Xing Rong, a neighbor. “And once my son was sick, it was a disease you would not understand but it had to do with the earth. Old Wu spit wine on to his hand and could see the problem by studying his palm. He then gently picked up my son’s legs and kissed them with his lips, like this.” Zhang imitated the fox spirit delicately taking his son’s legs and made a kissing noise.

“And then he was better. We didn’t even have to buy medicine, and in those days it only cost us five Chinese dollars.”

People in the village believe in the fox spirit, Zhang said, and consider its nearby presence a blessing. The village is between the mountain of Boluo Castle and a rural highway lined with shops. He was born here like his forefathers as far back as he can remember, he said. Each passing person who stood to stare and ask why a foreigner was walking through their village smiled and nodded their heads when told he was looking for the son of Old Wu. They quickly hurried on their way after a few words amongst themselves as the village had a wedding to prepare for. One woman named Chen Hua Hua, also reportedly possessed by a vixen spirit, helps the Lei family and looks after the village’s fox shrine, called Boluo Ting. It was built in honor of the Boluo Fox after the Cultural Revolution by funds predominantly provided for by Saiwa. She stood holding a hooked, wooden beam for carrying ceremonial buckets of water for the upcoming wedding. She recognized Old Wu as the former village fox spirit and excused herself to make ready for the newlywed’s arrival when firecrackers erupted back down the dirt path.

Following the path to the base of the village stands a thousand-year-old temple named Jieyin Temple, or the Receiving Temple of Boluo. The villagers nickname the temple, not the shrine near Old Wu’s house, the Boluo Fox Temple, Zhang said.

“We always respect it, and protect it when we could,” Zhang said.

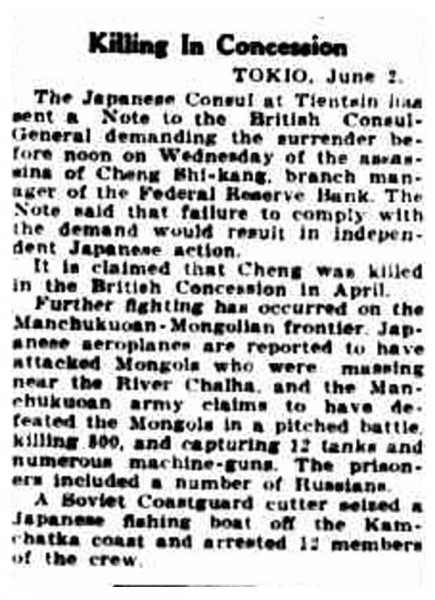

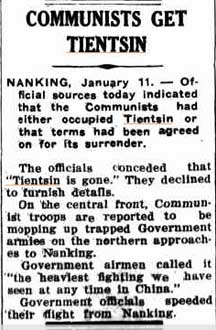

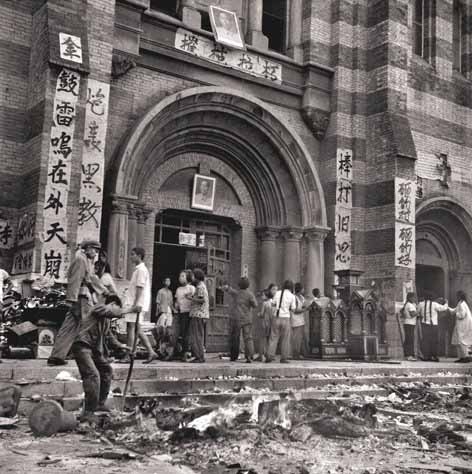

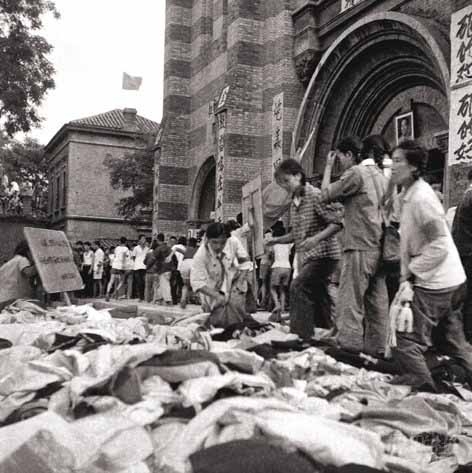

During the Cultural Revolution all superstitions, cult magic and shamans were vehemently banned throughout China. Old Wu spent three years of a seven-year sentence in prison. He became possessed by the Boluo Fox in the late 1940s and was imprisoned in 1959 during the Anti-Superstition Socialist Education Campaign.

After his release he continued to practice in secret, Ying said. Although the government suppressed him, among his clients were high-ranking cadres from the regional government.

Old Wu practiced in secret.

The fox clinic in those days was a hidden-away room, which was part of a more larger temple complex. There was room for three kneeling supplicants.

“He got out early because of good behavior and everyone liked him.” Ying said. “Plus the government then had nothing to feed their prisoners.”

The Jieyin Temple holds the deteriorated leftovers of an old sandstone carving of Buddha that dates back to the Tang Dynasty. A monk completed the carving after he saw a natural outline of Buddha in the stone. Historically, the carving is called Stone Buddha, and although the first temple was built around the 6th century A.D., it has withstood fire, wars, and attempted lootings by Mongolians, Chinese, British, French and Spanish invaders. Centuries of violence and bitter desert elements have reduced Stone Buddha to resemble a two-faced demon today, but a visage remains. Recent government funding that includes the restoration of the Boluo Castle above has breathed fresh life into the village and despite China’s hesitancy toward the belief of fox spirits or demons, holds two larger than life idols in respect for two fox spirits.

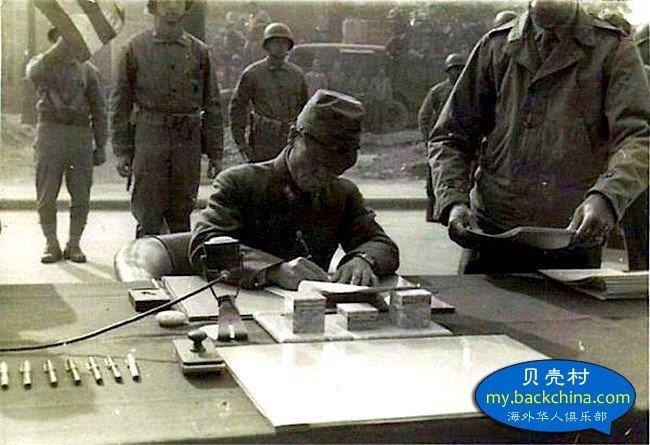

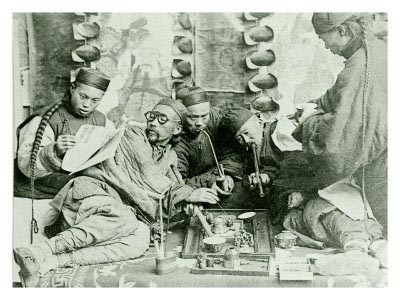

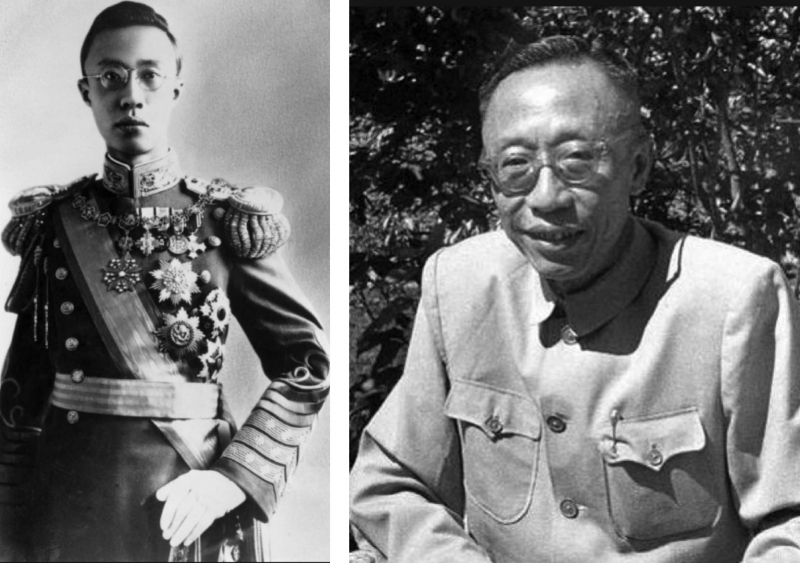

Jin Chan Laotzu, or Old Master of the Golden Chan, the original fox demon – at left – photo by C.S. Hagen

The Boluo Fox, according to temple documents, is named Jin Chan Laotzu, or Old Master of the Golden Chan, and it stands amongst the seven Diamond Kings of Heaven, the protectors or governors of the continents, beneath the carving of Stone Buddha. Each king is monstrous in appearance and size and carries a magical weapon. One holds Blue Cloud, a magic sword capable of bringing the Black Wind – a thousand spears in a single swing. Another king brandishes the Umbrella of Chaos, formed of supernatural pearls that can generate violent storms and earthquakes. Strangely, inside the temple shrine before Stone Buddha that stands more than thirty feet high, only the fox spirit appears humanly normal. Dressed in blue robes and a red cape, it stands with his hands raised, palms upwards, neither smiling nor frowning.

The Boluo Fox didn’t leave Old Wu until shortly before his death in 1994. Old Wu died of liver cancer and didn’t once try to cure himself, Zhang said.

“He was happy until the end.”

“But he was sad when the fox spirit left him,” Ying said. “The fox spirit went out and possessed another man not from this village. His name is Chen Saiwa and he lives in Yulin.”

Heading back down the path through the village and away from the ancient Boluo Castle, Ying stopped at the wedding as the newlyweds arrived. He grinned and talked to neighbors and cheered as madly drumming dancers past. Although Ying would admit to being nothing more than a keeper of his father’s temple, one glance at his leathered face and the lifelong friends gathering around him sharing cigarettes said at the very least, the son of lightning was a highly respected member of the small village.

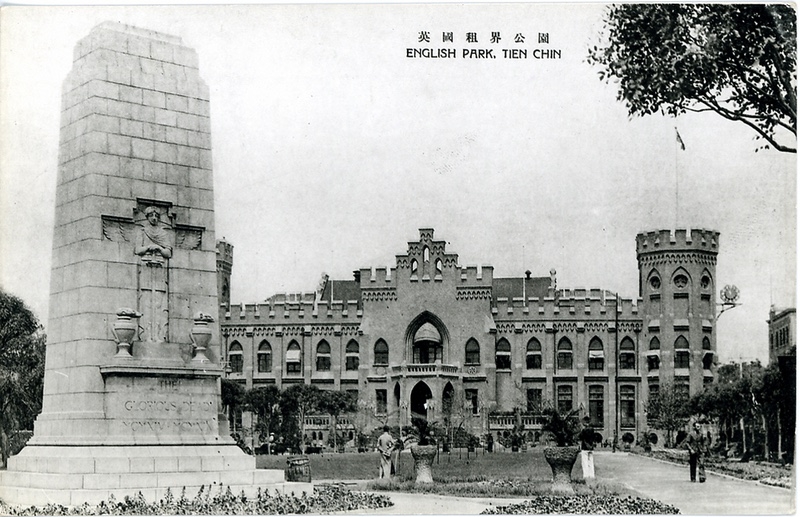

Boluo, an ancient fortress dating back to the Ming Dynasty, circa 14th century A.D., was built to protect China against the marauding hordes of Genghis Khan’s descendants. It borders Inner Mongolia and the western Ordos Desert. Once towering walls surrounded the city have mostly crumbled. The city gate still stands and a handful of people reside behind the walls. Some of the inhabitants live in grottos carved into hillsides. The Wuding River lazily winds and shines silver in the valley below. Crops grow in abundance and the smells of maize, barley and fennel fill the air.

It is a perfect lair for a fox, said Taoist Master He Lutong, from Tianjin.

“Only in the ancient, undeveloped areas can something like this happen,” Master He said. “Only where history is long and the traditions are real will foxes make their appearance.”

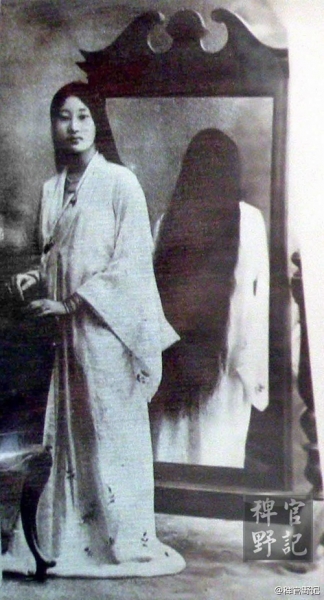

Spirits, he said, do not like the light and the bustle of city life. They prefer to reside where they are respected or feared. They predominantly prey on the sick and weak-minded. Legends of fox spirits are mostly as whorish vixens capable of sucking souls and eating the hearts of men. But once they’ve become a nine-tailed fox through mediation, knowledge and deeds, he said, whether by the high road or the low or the path of evil, they become the Goddess of Mercy’s messengers and sometimes assassins.

“The difference between good and evil as we know today are humanity’s definition, not the fox’s,” Master He said. “They have their own definition. Give an evil person or a good person a cure, it doesn’t matter to them. And sometimes an evil person’s cure may be punishment.”

A cure, perhaps, as in the legend of Su Daji, an evil vixen who corrupted the heart of a once righteous emperor and destroyed the Shang Dynasty nearly four thousand years ago. According to the Chinese texts such as the Lost Books of Zhou and the Investiture of the Gods, she enjoyed eating men’s hearts, inventing new ways of torturing her many enemies and the art of seduction. She was sent to destroy the emperor after he ridiculed Nüwa, one of the most ancient Chinese gods.

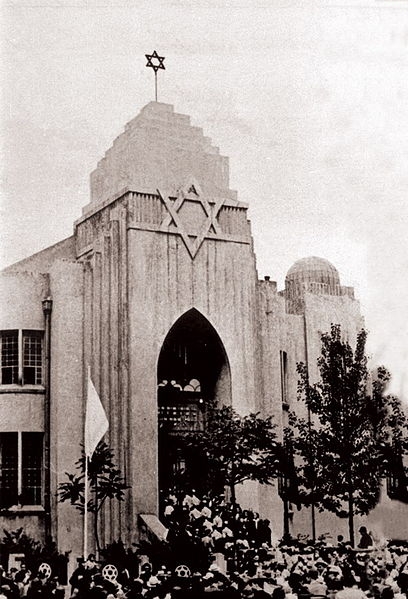

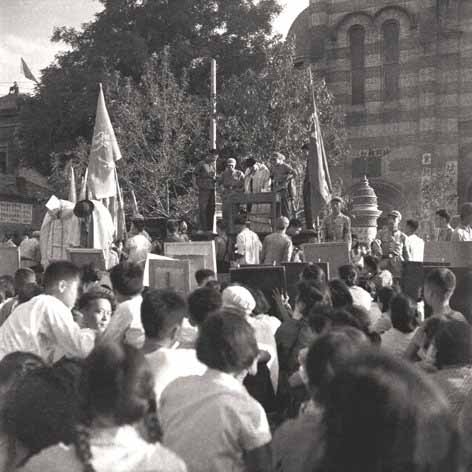

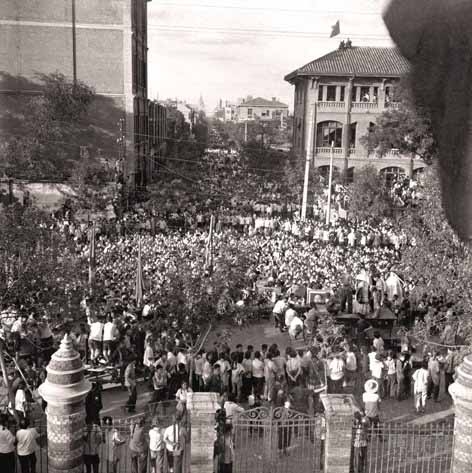

The fact that a kind-hearted fox spirit reportedly lives in Western China did not surprise Master He, and he made mention of another fox spirit enshrined in the Queen of Heaven Temple in Tianjin, a city of eleven million people near the country’s capitol.

“Granny Wang the Third was very good with the people,” Master He said. Although he had never heard of Saiwa or Lao Wu, he said their stories are similar. Granny Wang predominantly resided near Tianjin during the end of the last dynasty of China. Those were days of great poverty and affluence and worst of all, war, Master He said. But Granny Wang kept away from the rivalries, sometimes helping villagers escape peril at the hands of warlords and bandits. “You would almost never find her in the temples, she was always in the people’s homes, curing the sick and helping the people avoid calamity.”

Temple reports dating back to the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 say that she was a joyous person, always keeping herself busy until her death when one of the legends says she turned to stone inside Tianjin’s Queen of Heaven Temple. Her effigy remains there, and also at the Mountain of Marvelous Peak in Beijing, but she is unknown throughout most of China. She holds a vial of pills in one hand and people visit her to help with illness to this day, Master He said. They burn incense, bow three times, and rub her feet to cure illness, touch her hands to stay healthy.

“No problem was too little for her,” Master He said.

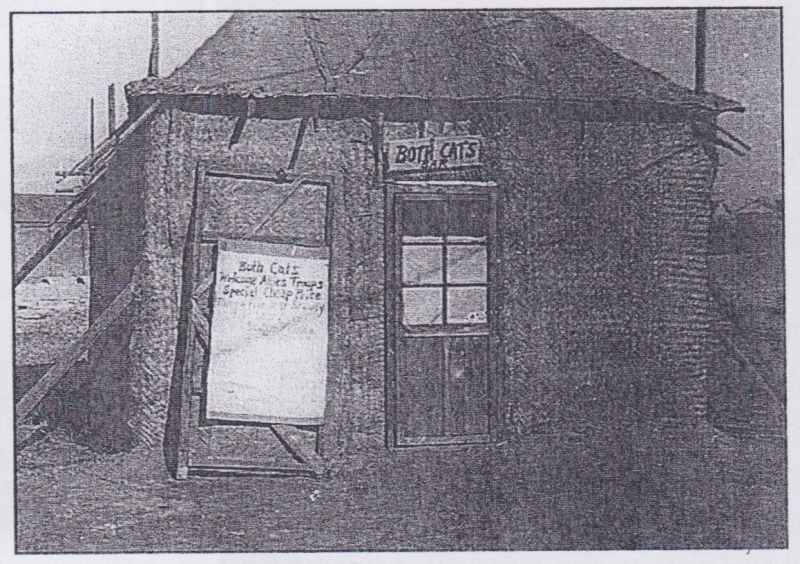

Mention her name in Tianjin to anyone born before the Cultural Revolution and they smile. “Big problem, little problem, Granny Wang will show,” said Boxer Rebellion Musuem curator Lin Xinqiao. He recalled as a child living in the crowded hutong streets of Tianjin where a shrine was dedicated to her. The shrine was torn down and her effigy thrown into the city’s main river during the Cultural Revolution, he said. As a child he remembers his mother paying homage to Granny Wang.

Across Asia worship of the fox is widespread. Some fear the spirit; others respect it. In China, the fox spirit is known as the huxian, or hulijing. In Japan, the kitsune lives on through the practice of worshipping Inari. Japanese families who are known as fox familiars reportedly raise foxes from generation to generation to achieve good fortune. In Korea the kumiho is a malevolent creature that enjoys eating human livers.

“In some places and instances it is known more or less as the opposite of Buddha,” Master He said. Although the fox spirit is a messenger for the gods, it can also help human kind achieve instant gratification for prayers. For instance, Master He said, a disgruntled wife whose husband is cheating on her or for vengeance of any kind. In the past in Southern China, rare instances of widespread panic have been attributed to the fox spirit for spreading a disease known as Koro. Koro is a culture-specific syndrome in which the person has an overpowering belief that his or her genitals will retract and disappear. Westernized doctors have treated such patients with psychotherapy, while in China Taoist priests beat gongs and incant charms to exorcise the fox spirit.

Taoist priests and legends generally agree that although vixens can be killed while in the form of a fox or trapped by experienced priests, peach wood, or toumuk in Cantonese, is the best weapon to use to kill them. A nine-tailed fox who has achieved the status by either the moral road or the path of evil, is very difficult if not impossible to kill, Master He said.

“Of course they exist,” Master He said while at his office. Two customers awaited him to have their fortunes read. “There is simply too much evidence throughout history and today to say they do not.”

Interview with the Boluo Fox

Before Saiwa became possessed he asked the Boluo Fox if it was willing to be interviewed. He invites the Boluo Fox when he needs but has no control over when the fox spirit will leave. After lighting four incense sticks, which he placed upon the altar, he lit a fifth curled incense and placed it underneath. He then kowtowed, or bowed three times before an effigy of Goddess of Mercy. Grabbing a carved canister filled with fortune sticks, he shook it until one fell out.

The answer was yes.

More than an hour passed before the final yawn and the possession was complete. The possessed Saiwa smiled frequently, and said he had met Westerners before but never for an interview. He drank periodically, straight from the bottle, coughed from the lower abdomen after each sip and kept one hand always behind his back.

“You desire information. Do not fear. I will not hurt you,” Saiwa said. He spoke Chinese but of an ancient form, one that is no longer used in modern China.

Saiwa, or the Boluo Fox, said he has no name. Neither does he need to eat or sleep. He has no humanly recognizable form any longer and is an assistant of the Goddess of Mercy. He said in human time he is older than 10,000 years and originally was a black fox that came from Mongolia. After crossing the Ordos Desert into Shaanxi he arrived in the form of a fox at the Stone Buddha carving before it was made. Upon entering the temple he injured his paw and The Goddess of Mercy took pity on him, taking him for a pupil.

Saiwa refers to himself only as “this monk,” and says many of the haunting stories of evil fox demons are little more than legend. The infamous Su Daji, concubine of the Emperor Zhou of the Shang Dynasty in 400 B.C., was not a fox spirit, he said. She was simply an evil woman.

“Just as with people, there exist the good and the bad. When this monk was in training this monk had many fox friends, just as people have friends, who were bad and tried to lead this monk astray. This monk made many mistakes. Many friends took the bad road. The xie dao (path of evil), is the easiest path.” The Boluo Fox took another sip from the bottle and shuffled closer.

“Hei-ki-ma-hei-ki-ma,” the Boluo Fox repeated each time he finished a statement.

He merely smiled when asked if he had ever eaten a human heart. According to ancient Chinese texts human hearts keep a young fox’s complexion after they learn to shape shift into human form. A human soul on the other hand, is far more potent. It is a powerful aphrodisiac to help them achieve immortality.

Besides healing the sick and protecting humans, one of his responsibilities, he said, was to ensure that other fox spirits do not stray from the path of enlightenment. He reins them in when possible, and sees that they are punished when he cannot control them. Though he has never met one, fox spirits are everywhere, he said, even in the United States. When Saiwa listens he squints his eyes and drinks deeply from the glass bottle of wine. Afterward, he smiles, like a rabbit and differently from the man before the possession. He appears older, greyer, eyes puffier but genuinely interested in answering any questions he can.

Some questions he said he was not allowed to answer. Questions about the progress of mankind through the centuries, the end of the world and if heaven truly exists.

“This is the first time we have met and you are the first Westerner to interview me,” he said. “There are many things this monk cannot tell you for this monk is but a servant of the Goddess of Mercy and does only her bidding.

“You ask this monk why this monk chose Lei Zheng Wu and Chen Saiwa? Chen Saiwa is but a dock for this monk to inhabit and perform her will. This monk looked inside them and saw our meeting was destiny.”

The two men are related, but not directly. Saiwa’s mother was Lao Wu’s wife’s sister. The Boluo Fox did not choose one of Lao Wu’s direct family to inhabit.

Outside of his host’s body, the Boluo Fox said it is impossible for humans to see his true form. While he was in training before the first dynasty of China, he had to learn to take the shape of a human. He had to eat and sleep, just like any other fox. It took him one thousand years to reach the Ninth Tail, or the final step in a fox’s road to enlightenment. His training included performing good deeds, like healing the sick, helping the injured and the poor, and above all, protecting human beings in any way he could.

When asked about the legends of other fox spirits eating human hearts or stealing qi and souls away, he avoided the question and said he was far above such practices now and that not all legends are true.

“We have rules that are enforced. If fox spirits break those rules they are punished. There are many legends about us and many roads we can take,” he rubbed a hand across his cheek much like a fox might while cleaning his paw.

“And there are many of us on earth, and not just in China. Hei-ki-ma-hei-ki-ma. This monk won’t be here forever but this monk will listen to the will of Buddha, whose most fervent dream is peace on earth and to fight against calamity.

“Hei-ki-ma-hei-ki-ma.”

Family Fox Feud at Boluo

At the village of Boluo no one doubts the authenticity of Saiwa’s claim that the Boluo Fox chose him as a medium, but Lei’s children forced Saiwa from their community.

“His sons in their hearts are not happy,” Wang Xinxin said. “They did not like him at first and they do not like him now. It is a family problem.”

Saiwa’s mother and Lei’s wife were sisters, Wang said. In keeping with the tradition of fox familiars, Lei’s family is jealous that the Boluo Fox chose someone outside of their immediate family. Even after Saiwa built the Fox Shrine behind Jie Yin Temple in the late 1990s, the Lei family keeps watch over the shrine but does not want Saiwa to return.

“Old Wu’s family is jealous of me after I built the shrine,” Saiwa said. He spent upwards of eight hundred thousand Chinese dollars in constructing the memorial to the Boluo Fox. “It isn’t important that I go back, the Boluo Fox wants to return. Boluo has been his home for a very long time.”

Ying refused to speak on the matter.

Despite the family opposition, Saiwa is content and happy that he allowed the Boluo Fox to use him as a medium for healing. He has learned how to read and write and spends his spare time studying Buddhist scriptures. He receives patients daily and said the possession is sometimes painful.

“It was unpleasant at first,” he said before the Boluo Fox possessed him. “There is a pain or more like an emptiness in my head. When it’s over I remember nothing during the time he possessed me and I must lay down for an hour or so before I feel better.”

Thinking back twelve years before when he first encountered the Boluo Fox he said he did not believe such creatures existed when he was young.

“Now my days are simple. I am a simple man and do not regret my decision.” Saiwa married after he accepted his fate of being the “port” or caretaker for the Boluo Fox. He sired two children, a boy and a girl, both of whom accept his role as a shamanistic fox medium.

“My wife thought I was crazy at first,” he said. “But through the years she has accepted our fate. Our children have never been sick. Not once.” When the Boluo Fox possesses him, his friend and patient Wang said he speaks with the same voice as Old Wu. They both use the same methods to cure the sick.

“He even looks and acts the same,” Wang said. “Many people from Boluo come here to Yulin to get healed,” he said. “And you pay as you can, usually people pay 30 to fifty Chinese dollars but its up to the individual. Saiwa will not turn anyone away even if they cannot pay.”

Saiwa says he cannot cure all sicknesses however, some patients he leaves to the hands of science and modern medicine. He openly admits his skills, once possessed, cannot cure every ailment. A 24-year-old man whose muscles were deteriorating was once brought to him for consultation. The man was taking illegal drugs, Saiwa said. His parents did not know and the young man refused to admit his addiction until the Boluo Fox told them what his problem was.

“They told me what I said after I woke,” Saiwa said. “At least now they can seek proper care and treat the real problem and not just the symptoms.” Saiwa said no matter how the Cultural Revolution repressed shamanism and mystic beliefs, there are many like him throughout China, some of whom are imposters seeking recognition. His patient, Wang, agreed.

“There are a lot of bad foxes out there,” Wang said. “Back in Boluo there is a woman there who claims to be a fox spirit as well, but I don’t believe it is true. I haven’t heard of any bad foxes that have done terrible things, it’s more like they are fake, and will treat you for an illness but you walk away feeling even more uncomfortable than when you arrived.”

Saiwa has been treating people from Boluo, Yulin, Inner Mongolia and Xi’an for more than twelve years. Hanging from the walls of his clinic are crimson silk banners, each one in recognition for his healing work. Hanging closer to the altar are strips of blue paper, also giving testimony to those he has healed.

“If I treated someone improperly and that person died, no one would believe in me,” Saiwa said.

Wang described how Saiwa told him of a time when Wang had been in a traffic accident and burned his leg. Local doctors could not heal his injuries and the wound became infected. At one point doctors in Yulin told him he would lose his lower leg. As a truck driver Wang could not continue his work without the use of both legs and he turned to the Boluo Fox for assistance.

A foul smelling tincture of boiled herbs, bean paste, and yellow wine then administered by the hands of the Boluo Fox cured him.

“The hospital could not heal me, they said they might have to take my leg,” Wang said. “But he healed me within three days. There are many things that are hard to believe, but I’ve seen proof enough and I do believe.

“The Boluo Fox is real.”