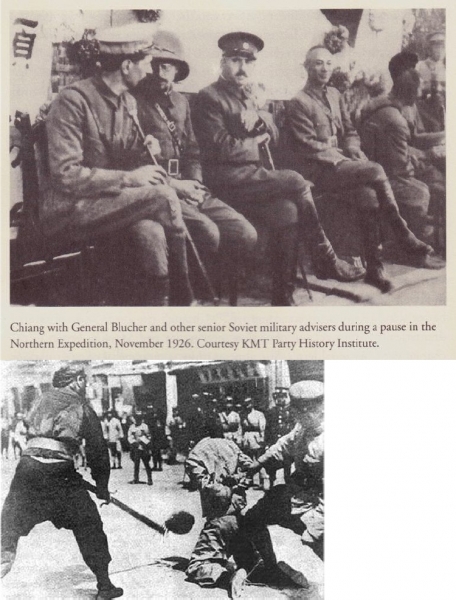

How a Valley City German immigrant saved more than 125 German Jews from the Holocaust

By C.S. Hagen

FARGO – In 1933, “Onkel” Herman Stern received a coded letter from a relative called “The Chammer.” Postmarked Venlo, Holland, containing one word, typed in capital letters and double-spaced.

U N B E L I E V A B L E

A warning followed: “Before saying one more thing – I must warn you never to refer to it in a letter… Whenever you write just say ‘I’m in receipt of your letter from Holland and glad to learn that everything is okay’”

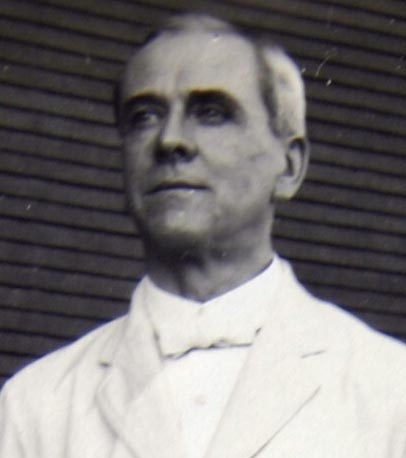

Herman Stern 1929 – photograph provided by Department of Special Collections, Chester Fritz Library UND

The Chammer spent his savings to travel by train from Nazi Germany to Holland, where outgoing mail was still safe from prying eyes, and described in detail the atrocities he had witnessed in his German hometown. Four Jews shot and killed, no arrests, no police interference. Six Jews in one day committed suicide. Forty-five Jewish bankers arrested. A Jewish friend in Worms was locked in a pigpen. Doctors were quitting. Lawyers no longer had access to their black legal garments.

“The Jehoodems [are] done for in Germany and this is what happens every day,” The Chammer wrote. “Never say anything that you are sorry you heard about the cruel treatments. If you do write this and the letter happened to be censured, they will be SHOT to death, SHOT, SHOT to death.”

The letter was just one, still safely guarded at the UND’s Chester Fritz Library Department of Special Collections, that alerted Stern that the Nazi threat against Jews was more than hate speech.

A radio program on WCCO in 1933 led by Rabbi Albert Yannow also put the situation into focus for Stern. One listener wrote in to the radio station saying: “I am with Hitler for trying to put Germany again in the sun, out of which France, and indirectly the Allies have forced it. The Jewish question, to me, is the outcome of a hysterical condition there. Injustice has ever been the Jew’s lot. That seems to be his fate – to suffer and endure.”

The youngest of eight children born to a poor Jewish family in Aberbrechen, Germany, Stern rekindled contacts involved with immigration and one by one, and began saving his family. Their names are scrawled in a well-worn ledger.

In all, Stern saved more than 125 people from near certain death at Nazi hands. Showing foresight, he started early. As president of Straus Clothing Company, he had funds, some land, but more importantly, Stern was respected, and had a friend in the United States Senate in Gerald P. Nye, who quietly helped Stern obtain immigration visas for his German relatives.

During a time when anti immigration laws turned Jews away by the shiploads, Stern also found a friend in former North Dakota Governor John Moses, a Norwegian immigrant who campaigned for office speaking Norwegian, German, and English, and later defeated Nye for his seat in the U.S. Senate.

Fifteen boxes of paperwork at Chester Fritz Library tell the complicated story of how Stern saved his family, many of whom were distantly related. Some were smuggled out of Germany under blankets by the French Resistance, and routed to Cuba, Chile, or Panama to wait for U.S. visas. Another managed to escape to Paris, and then later on to Casablanca.

“He couldn’t save his brothers, and that bothered him for the rest of his life,” Stern’s grandson, Rick Stern, said. “He tried, or they were too late.”

Herman Stern’s grandsons look over a well-worn ledger with a list of those who were saved – photograph by C.S. Hagen

Stern’s story has had little media attention, and virtually none during his lifetime (1887-1980). Recognized for many awards, perhaps the most prestigious for Stern being the posthumous Theodore Roosevelt Rough Rider Award and the Boy Scouts of America’s Silver Buffalo award, little was said about him saving more than 125 Jews from Nazi internment. A monument was also erected for Stern at the Veterans Memorial Park in Valley City in October 2016.

Since the movie “Schindler’s List,” Stern’s story has been gaining attention, including a book written by Moorhead resident Terry Shoptaugh entitled “You Have Been Kind Enough to Assist Me.” Additionally, a documentary on Stern’s life will be released this month by Visual Arts Studios in Fargo entitled “The Mission of Herman Stern.”

While on his deathbed in Fargo, 1980, Rick read the Silver Buffalo award to his grandfather, one of the only early mentions of him being a Holocaust rescuer.

“During World War II you helped more than 100 persons who were in great danger of concentration camps or death in Europe to come to this country,” the biography on the Silver Buffalo award said of Stern.

They were the last words Stern heard, Rick said. His reply, like the way he chose to live, was simple, honest, and humble.

“Well, that’s nice,” Stern said.

“I was there when it was time,” Rick said. “Have you ever been with someone when they passed on? This was so beautiful, so magnificent. We were just talking, he coughed a few times, and then I felt his spirit rise.”

Petitions for help from German Jews 1930s to 1940s – letters provided by Department of Special Collections, Chester Fritz Library UND

Stern remembered

Stern committed one dishonest act to fulfill his dream, Rick said. He ran from a clothier apprenticeship in 1903. In those days, an untrained apprentice’s contract had to be purchased. His family was poor. His father worked in a packaging company and had many mouths to feed, and Stern was a dreamer.

“All Grandpa could think of was coming to America, that was the land of opportunity,” Rick said. “Grandpa was a little like Jacob, he was sent by the Almighty here so he could rescue his family. And he did.”

Stern never spoke about anti-Semitism in his youth, Rick said. “That’s why it was so disturbing for him when it came up. His only tangible brush with real hate came while he was walking with his wife in Valley City, and came upon a Ku Klux Klan rally cross burning at a local park. “It gave him the creeps,” Rick said.

In 1903, still a teenager, Stern boarded a ship to America. Morris Stern, Herman’s uncle, and a position in Straus Clothing awaited him in Casselton. By 1908, Stern moved to Valley City, married Adeline Roth in 1912, and by 1920 was owner and manager of Straus Clothing in Valley City, the place he would call home for the rest of his life.

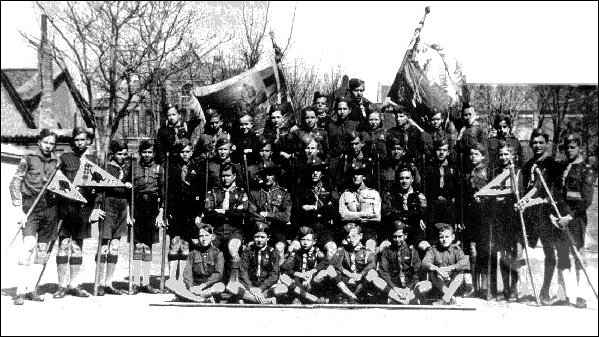

He lived through the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, two world wars, and came out on top, but never flaunted wealth. He was active with the Boy Scouts, war bond recruitment drives, later with the United Way, the Rotary Club, Masonic Lodge, the Greater North Dakota Association, which became the Greater North Dakota Chamber, and much more. A memorial was erected in his honor in Valley City in October 2016.

“Whatever was positive for Valley City. Boom. He was there,” Rick said.

In the home, German was reserved for Stern and his wife. His sons never learned the language, it was forbidden when the German Kaiser Wilhelm II waged the First World War.

Before the Second World War, Stern founded the North Dakota Winter Show, the state’s oldest agriculture and livestock show.

“On that day, I remember the dedication,” Rick said. “They pulled this thing down and a big banner dropped revealing the ‘Herman Stern Arena.’ He was so upset, he fell off the stage, and he had two questions afterward: how much did it cost, and who authorized it.”

Shortly after Stern’s death, snow collapsed part of the building’s roof, destroying the commemoration sign. “People said, ‘That was grandpa,’” Rick said. “He never liked that sign. He was humble.”

Stern kept himself busy until just before his death at 92 years old.

“He was righteous,” Mike Stern, Rick’s brother said. “I remember I disappointed him once, and I still feel really bad about it.” While coming home from Camp Wilderness, Mike stopped at Lake Melissa to say farewell to friends. He arrived home 30 minutes late, and found his grandfather worried he had been involved in a car accident.

“When your grandfather that you worship says, ‘I’m very disappointed in you,’ that’s something you can’t forget,” Mike said.

The “blessed grandson,” Rick, once borrowed a car and slid on ice, smashing in the rear end. He was able to drive it home, but Stern reacted differently, which ended in a family joke. Stern offered to sell Rick the vehicle, and Rick reminded him not to set the price too high as it had been involved in a bad accident.

Both brothers’ first memory is their grandfather, sitting cross-legged, bouncing them up and down on his knee while humming a German tune.

“We all compare ourselves a little to those who passed before us,” Rick said. “But I feel we all fall so incredibly short of him. We do our best, but it just can’t compare.”

Straus Clothing Store – photograph provided by Department of Special Collections, Chester Fritz Library UND

Holocaust rescuer

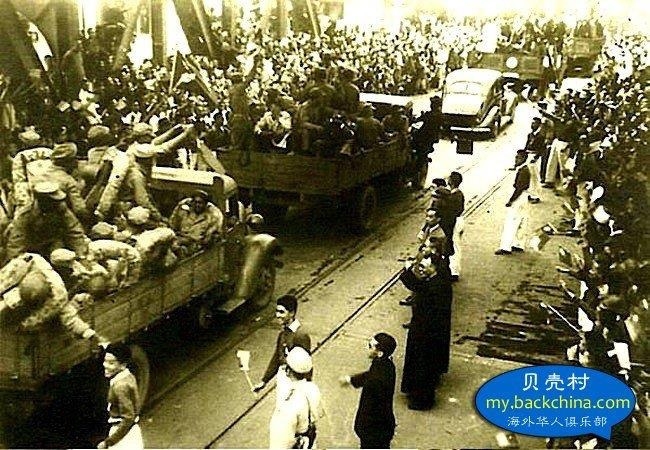

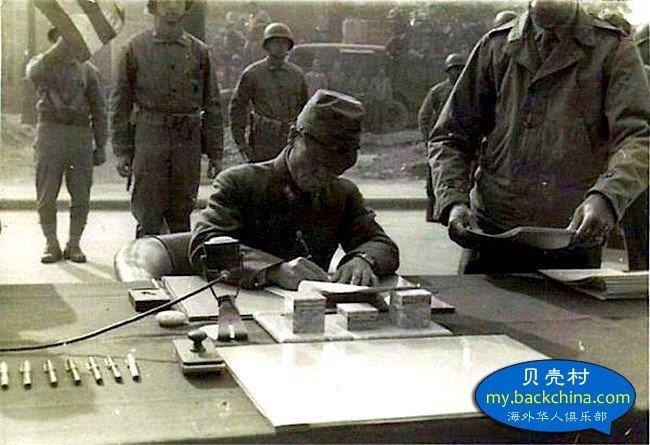

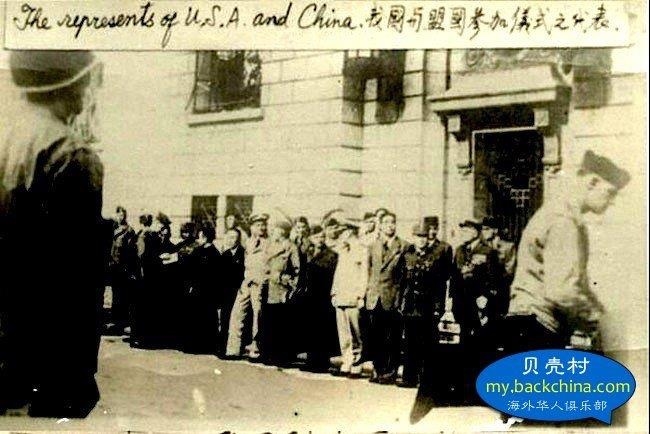

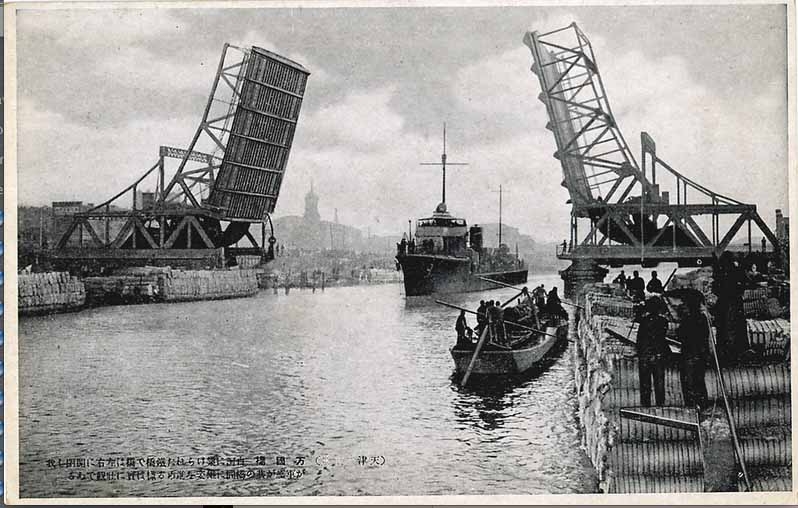

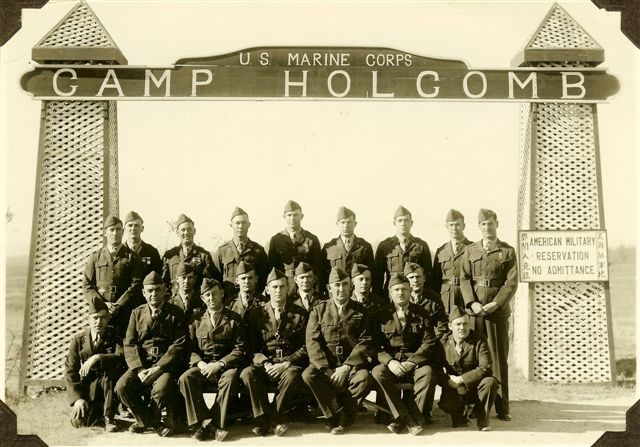

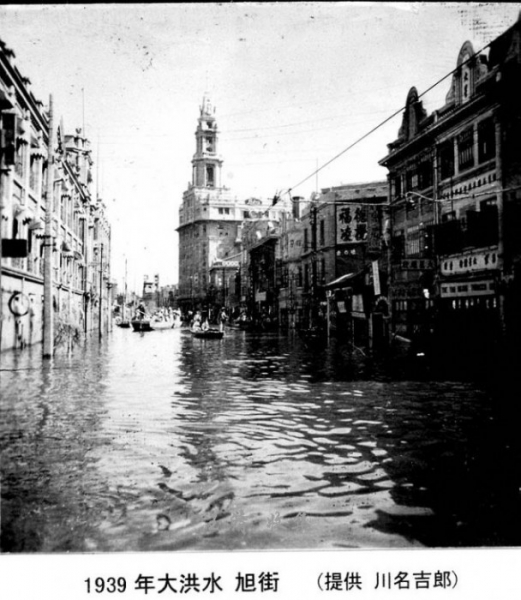

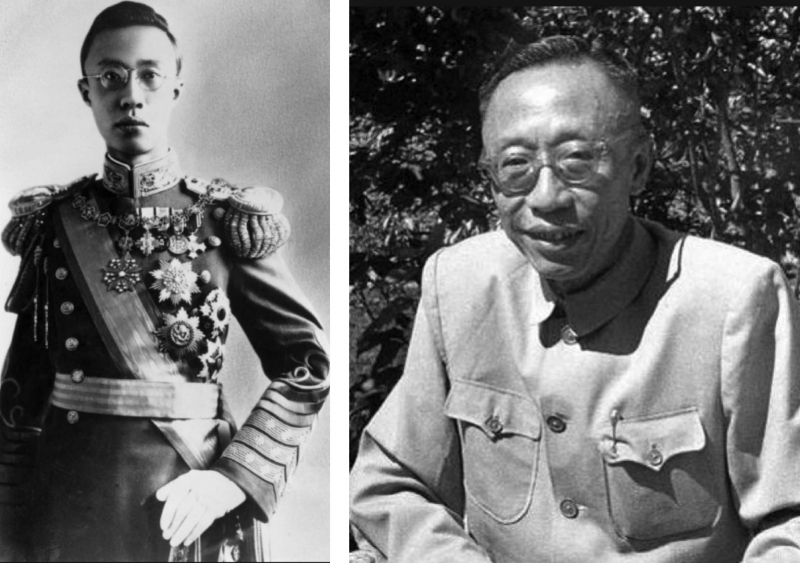

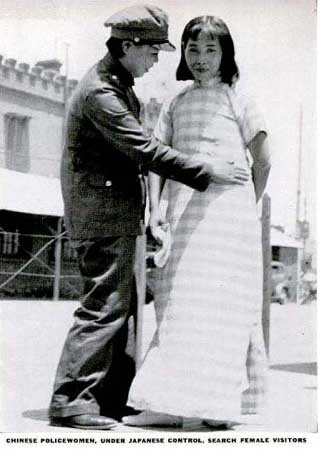

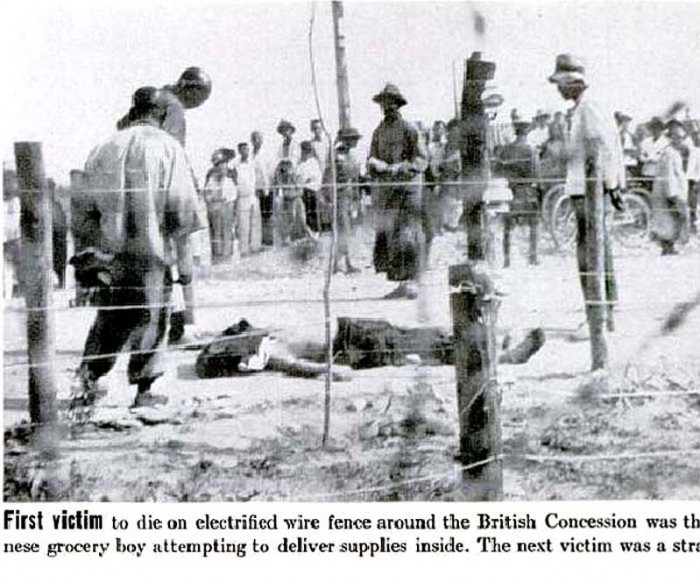

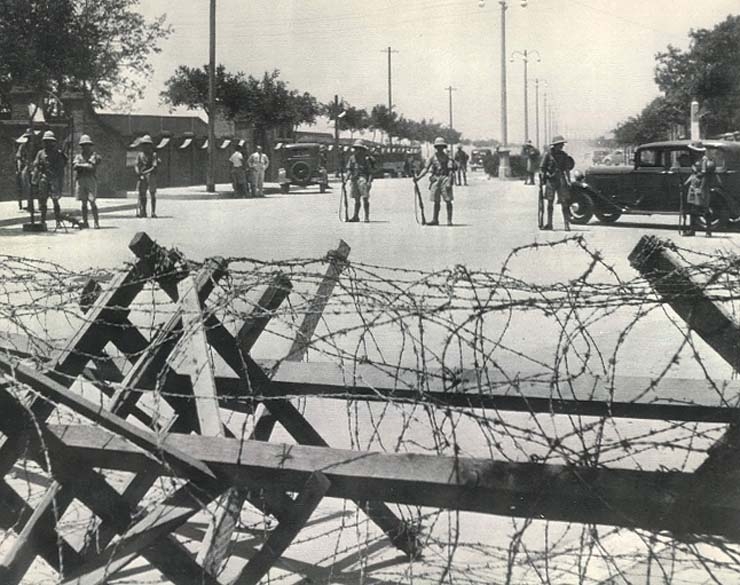

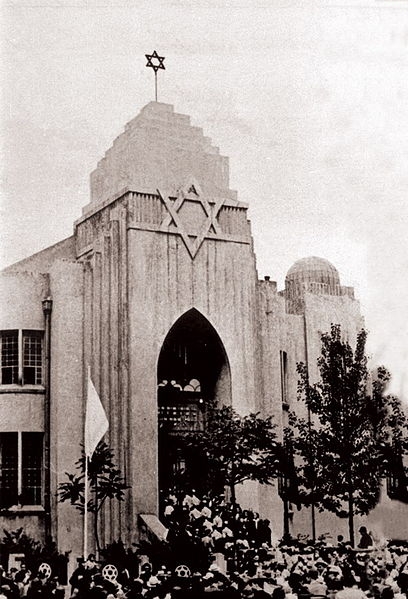

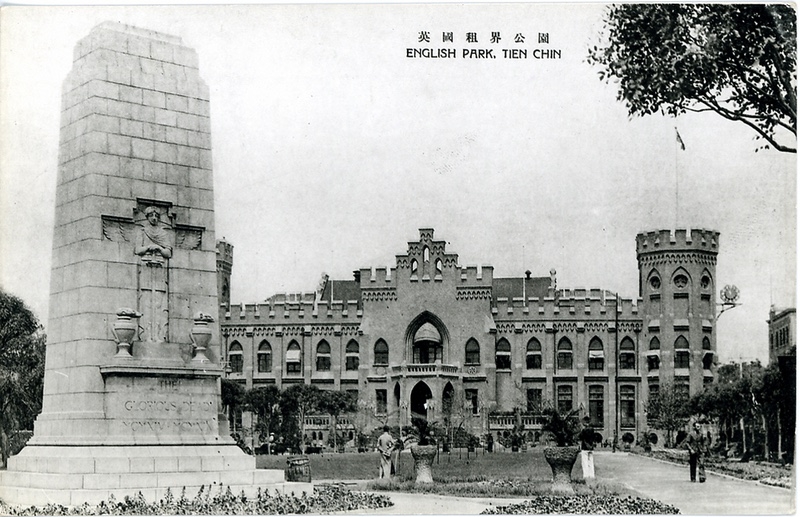

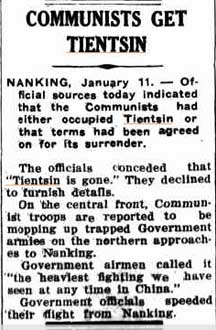

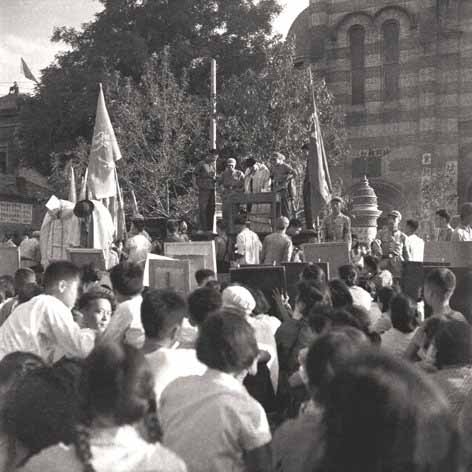

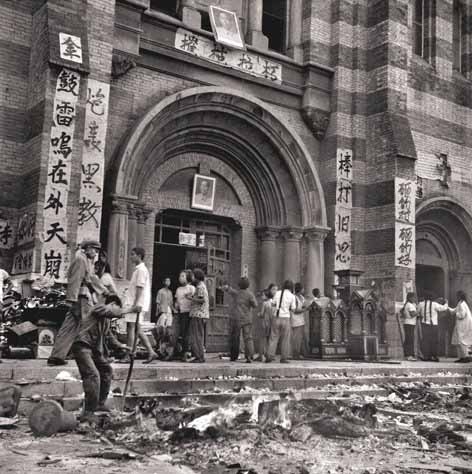

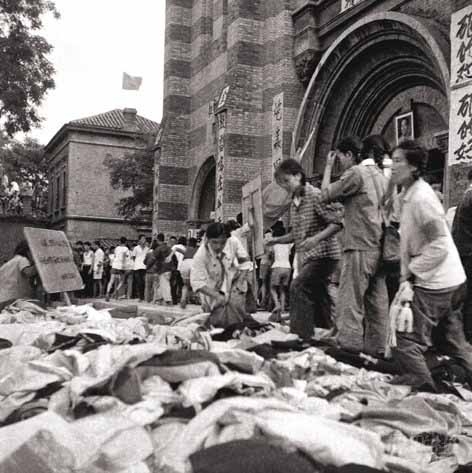

America eventually opened its doors to Jewish refugees fleeing Nazis, but the help came too late in 1944. Many European Jews were forced to return to Europe after arriving in the United States. China was one of the only countries that allowed Jews to enter, accepting nearly 23,000 Jewish refugees who found relative safety in Shanghai from 1941 to 1945.

Even after World War II finished, liberated Jews emerged from concentration camps and from hiding, ill, exhausted; and discovered a world that seemed to have no place for them.

Stern’s efforts started in the 1930s, years after he brought one of his brothers over from Germany. He needed to prove himself, and show he could support every refugee he vouched for; personal affidavits of his financial worth were needed for every case.

He had a net worth of $50,000, was a shareholder of Straus Clothing Company, owned 320 acres of farmland near Valley City, another net worth of $5,000, according to affidavits filed with the American Consul General in Stuttgart, Germany.

Letters of repute were also needed – for every single case. He obtained these from Fred J. Fredrickson, mayor of Valley City. “During all this time Mr. Stern has been one of the most progressive and substantial citizens and businessmen of our city and state,” Fredrickson wrote.

At first, his petitions seemed to fall on deaf ears. He needed to change the narrative, and find influential people who could help persuade refugee legislation. Correspondence between the National Refugee Service, National Council of Jewish Women, Jewish Welfare Society, Hebrew Sheltering and Immigration Aid Society of America, was frequent.

In 1938, Stern wrote to the American Consul General in Germany, hoping to relieve bureaucratic worries. Some affidavits were rejected, as in the case of Dr. Rudolf Mansbacher, a nerve specialist from Germany who had an affidavit written by an American doctor and was not recognized by the American government.

Senator Gerald Nye – mid 1930s – who quietly helped Herman Stern obtain immigration visas for German relatives – photo provided by Department of Special Collections, Chester Fritz Library UND

“My sponsorships may seem perhaps excessive to you compared to the financial statement, but I can assure you, my dear Consul, that all the immigrants have and will be properly received who are coming in my care. Every immigrant has received a proper home, not alone through my efforts, but also through the assistance of my friends.

“You may be satisfied without any doubt whatsoever that I shall continue to carry out the pledge and that none of the immigrants sponsored by me will become a public charge, but on the contrary, will become useful citizens.”

And many of Stern’s family did. Some joined the war effort. Others found work on farms. Stern searched out hospitals, nursing homes, and area doctors willing to offer qualified refugees work.

Doctors were needed in American hospitals, a 1939 pamphlet from the American Medical Association reported. From 1934 to 1938, during the rise of Hitler’s National Socialist regime, 1,528 physicians migrated to the United States, of which 75 percent were Jews. During the same years, the United States had 170,000 physicians, which meant one doctor for every 784 people.

Despite the need for qualified doctors, the system was rigged against him. Few doctors from Europe could pass American medical standard tests, and needed further training. Stern began looking into medical schools.

“After making further canvass I am still of the same opinion that fifty doctors could be placed in our state, but at present our hands are tied,” Stern wrote to Charles Jordan of the Central Committee for Resettlement of Foreign Physicians on July 1, 1939. “All we can do is to interview our prominent doctors all over the state and see if we can in some way influence these men so they will gradually recommend modifying the rules and attitude of the National Organization.”

Stern found an empathizer in Dr. Irvine Lavine, who assisted placing refugee doctors around the state.

Fresh off the boat after journeys circumnavigating the globe, many stayed at the Stern family house in Valley City after they first arrived. Gustavas Straus traveled through Trinidad, Hans Wertheim through Chile.

Mike remembered stories his father told him of frequently having dinner with relatives he had never known. “Our dad was a little upset sometimes – he was young – because he couldn’t get seconds or thirds,” Mike said.

Nobody went hungry. Stern’s wife, Adeline Roth, 22 at the time, never wavered in her support for her husband’s efforts, Rick said.

In 1939, Stern had a scare. A medical report from the Dakota Clinic in Fargo reported no disease had been found on his heart after X-rays. The pain he was experiencing then was probably stemming from muscle or nerve issues, or more likely, although the medical report made no mention, from the stress of trying to save his family.

On March 27, 1941, two years after World War II started, Stern wrote to the National Council of Jewish Women in St. Louis, Missouri.

“I am endeavoring to gain admittance of four adults and two children into Cuba as a temporary quarter until it is possible to gain visas for them to come to the United States of America. The relatives in question are now living in Paris. They are not French citizens, but are refugees from Germany.

In order to obtain permission to travel to Cuba, Stern was told to deposit $2,000 per person in a Cuban bank, with $500 bond placed with the Cuban government, also for each person, plus two round trip tickets, and lawyer fees up to $250.

Records safely tucked away in box nine at UND’s Chester Fritz Library Department of Special Collections, end before 1944, and Stern had already found ways to bring more than 125 refugees to North Dakota. Most dispersed across the nation, few remained behind, Rick said.

Most of the letters to Stern are in German, written by hand in impeccable penmanship reminiscent of a medieval scribe translating holy texts. Other letters are typed, but there’s little need for a translation.

The Talmud translates best: “Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.”

“I don’t know how to thank you,” a letter written by Hans Wertheim in 1939 to Stern said. “You may be sure that we shall never forget your kindness and what you have done for us. We are glad to know that there are people who are willing to help us.”

“In later years people would say, ‘We owe you so much,’ but he would say, ‘No, you don’t owe me anything,’” Rick said.

Stern kept his efforts mostly quiet, except to his family. He never wanted the publicity or the acknowledgement, he only wanted to help steer men and women toward successful futures.

If Stern were alive today, sitting around the dinner with friends and family, Mike, his grandson said he would know how to answer questions about society’s recent polarization. He might pound the table dynamically with a fist, but his thick German accent would be impossible not to listen to.

“I think Grandpa would be welcoming immigrants and trying to get them plugged into the community, into Boy Scouts, or joining the church,” Mike said.

A short pamphlet Stern wrote and used to pass out, explains his views perfectly.

“Without strength of character, we are a ship without a rudder, lost in the sea of no return… Respect the views, practices, and habits of others. Be more than tolerant, be understanding. In dealing with people, learn to respect and understand their position. Judge an individual not on his race, creed, or economic standing, judge him for what is in him.”