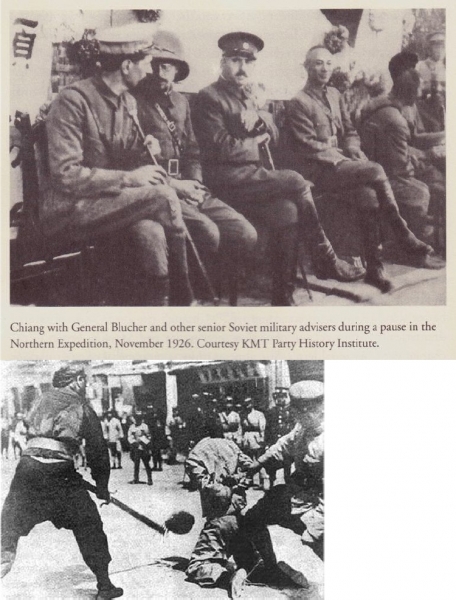

This is the ninth story in the “Tientsin at War” series. The pinnacle of Japanese success during World War II meant the downfall of Western colonialism in Asia. Nearly 750 foreign enemies of Japan were arrested, marched “in shame” through Tientsin’s streets and sent to prison in Weihsien, currently Weifang, Shandong Province, China. These are their gripping stories of survival, the memories of heroes.

This is the ninth story in the “Tientsin at War” series. The pinnacle of Japanese success during World War II meant the downfall of Western colonialism in Asia. Nearly 750 foreign enemies of Japan were arrested, marched “in shame” through Tientsin’s streets and sent to prison in Weihsien, currently Weifang, Shandong Province, China. These are their gripping stories of survival, the memories of heroes.

By C.S. Hagen

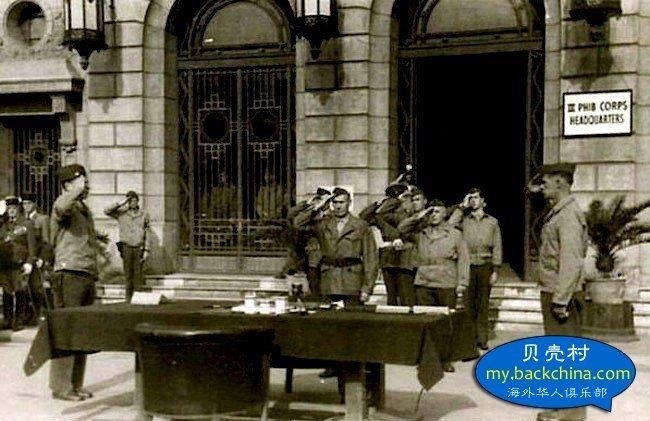

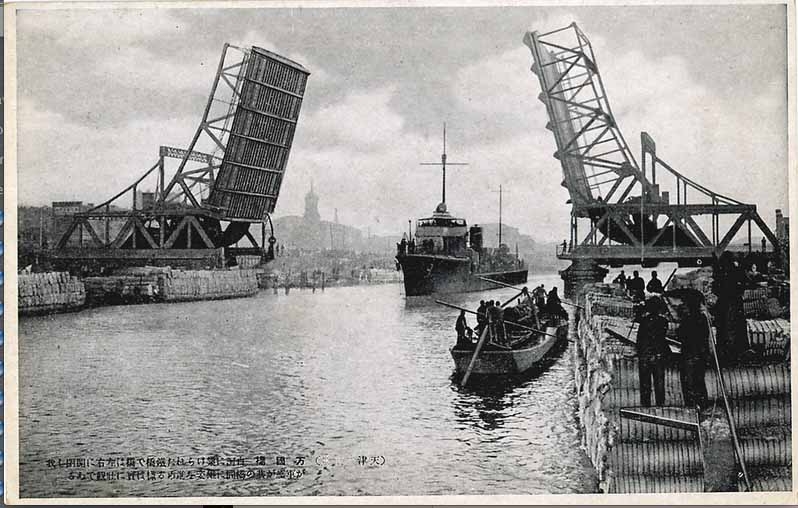

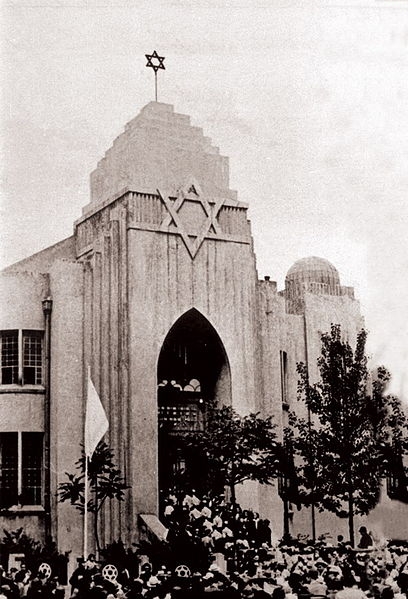

TIENTSIN, CHINA – Colonial rule in Tientsin ended with three whimpers. The first was one of the city’s most heart-stirring days, according to historian, author and Tientsin native Desmond Power.

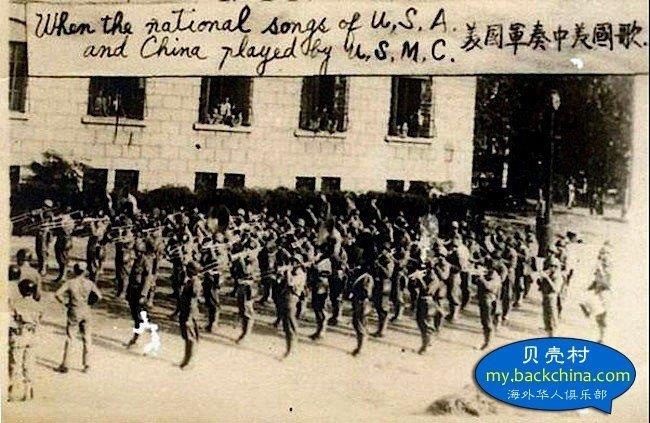

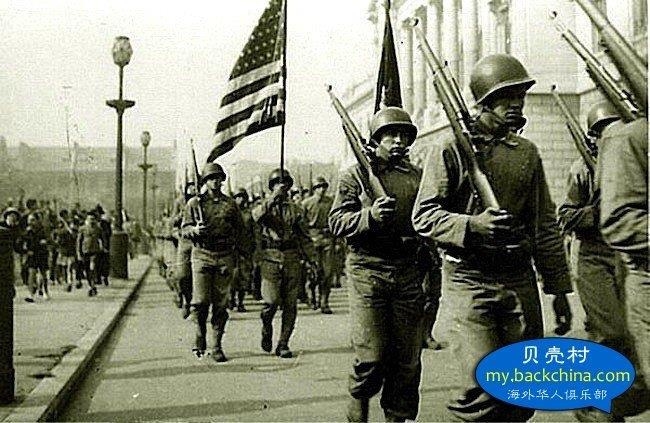

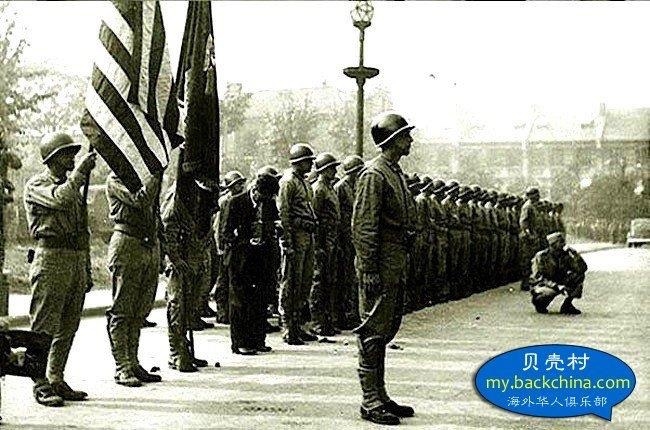

English military battalions such as the First Lancashire Fusiliers, the Second East Surrey Regiment and platoons of the Tientsin British Special Police lined the streets to bid US troops goodbye.

“And here they come,” Power wrote in his book Little Foreign Devil, “the band crashing out Stars and Stripes Forever. Then the men, nine hundred strong, marching shoulder-to-shoulder, grinning sheepishly at the ovation. And a deafening ovation it is with all that shouting and cheering and handclapping and firecrackers. Women break through our cordon and fling themselves on their departing sweethearts.”

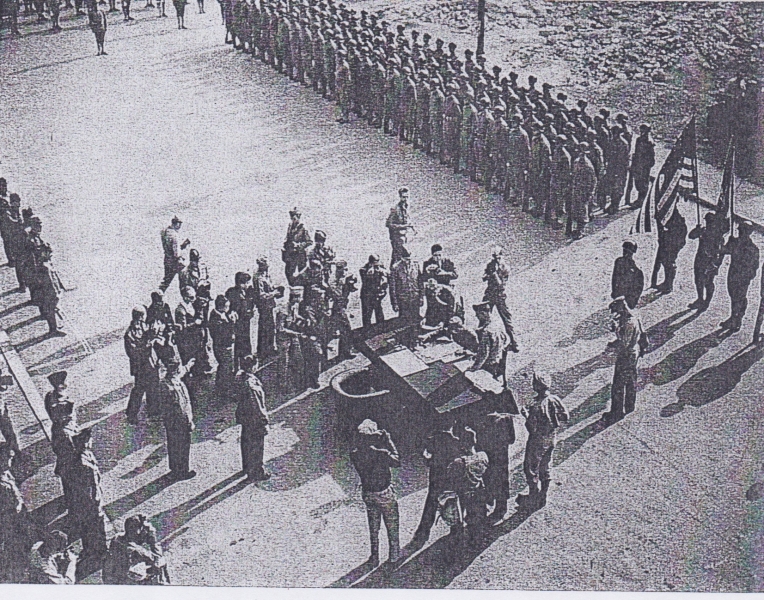

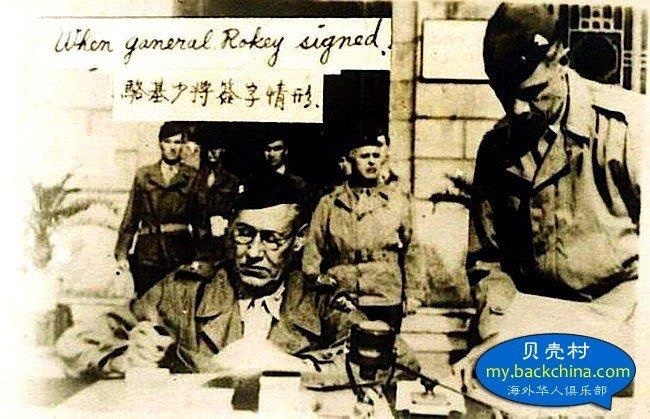

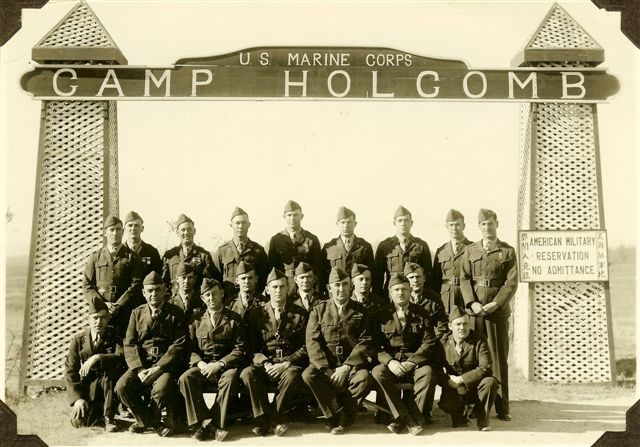

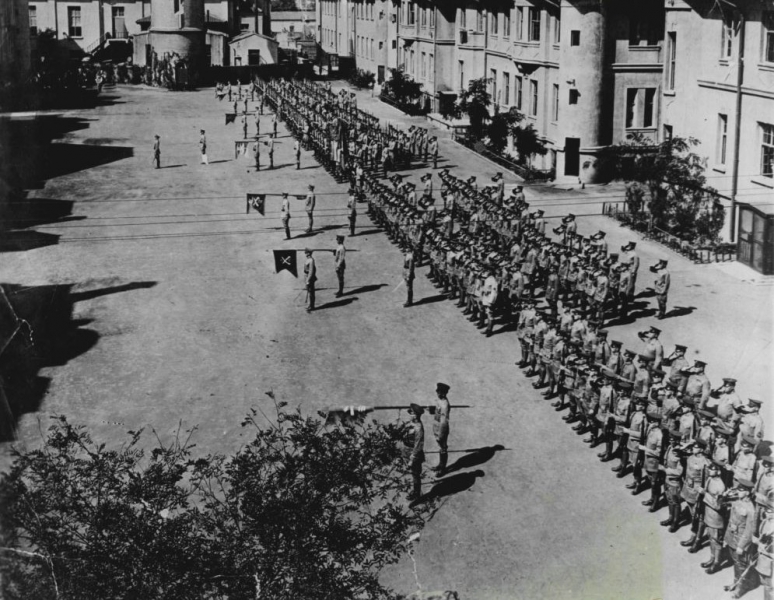

America’s Fifth Infantry on parade in Tientsin – 1931

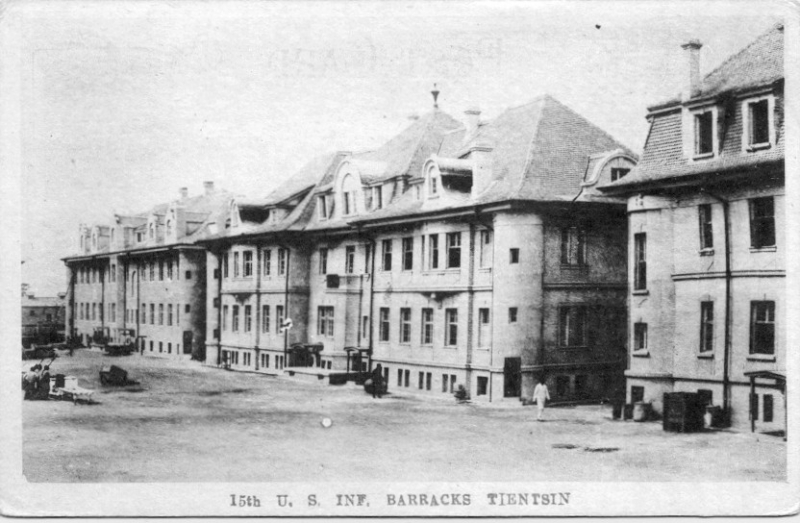

By 1938, one year after Japan’s invasion of China began, the situation in Tientsin had become untenable, according to the Assistant Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs Walter Adams. The US Army Fifteenth Infantry was withdrawn from Tientsin and was replaced by a token force of US Marines.

“It’s all over…” Power wrote. “The crowd filters away. A breeze disperses the lingering wafts of burnt powder, but it will be hours before the sweepers deal with the litter of spent firecrackers.”

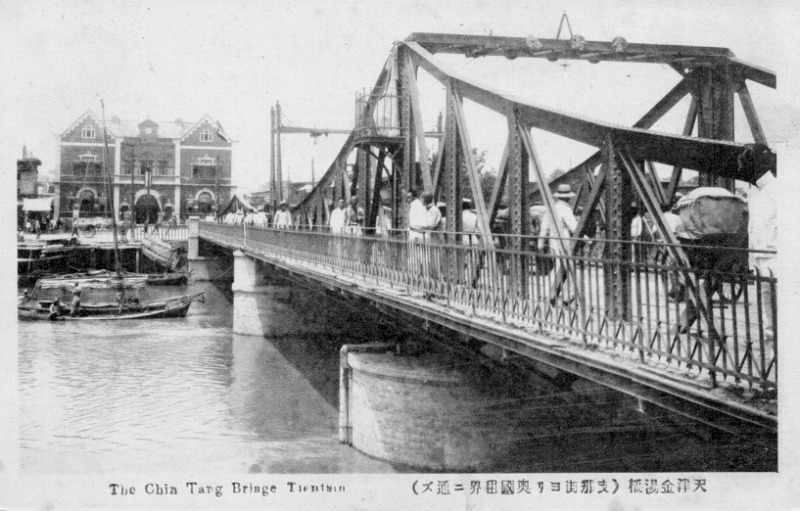

The second whimper came two years later and “without notice, without fanfare, without the roll of a single drum, the beep of a single fife.” With war raging across the globe, Great Britain called the Tientsin’s East Surrey Regiment to Singapore. British troops marched for the last time north on Victoria Road, laid in part with bricks from Tientsin’s old “Celestial City” wall, demolished after the Boxer Uprising in 1900.

“For the first time since its inception in 1863, the concession was without the protection of the Imperial Army,” Power wrote. No one truly thought colonial life would ever end, much like the Edwardian Era; the good times would last forever.

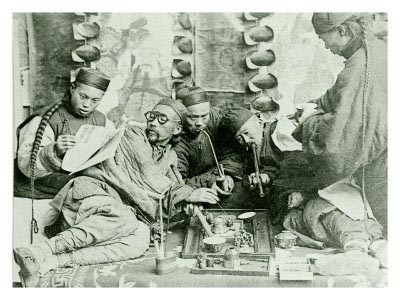

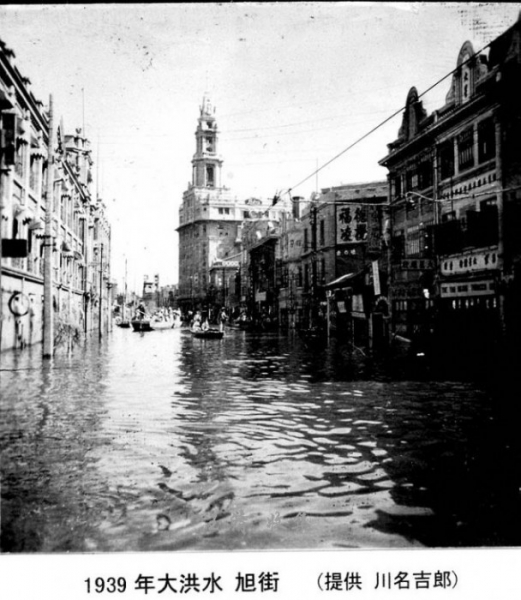

But mayhem reigned. Chinese protests of the Unfair Treaties endangered British Commerce. Japan’s navy blockaded Tientsin’s port. Policemen went on strike. Opium and heroin were easy vices, the drugs were smuggled across the Hai River by Japanese gangs and sold into every city district, demoralizing and lethal.

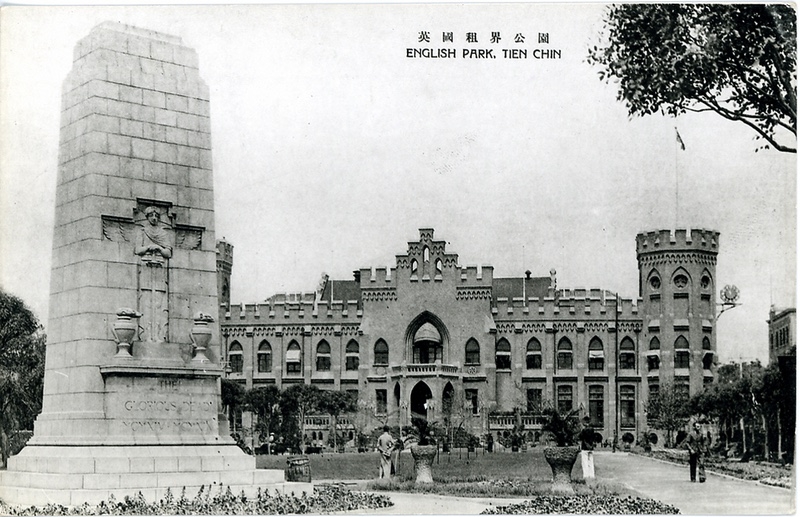

The yellow emergency flag replaced the Union Jack on the topmast of Gordon Hall, Tientsin’s political center and formidable castle, which to the Chinese was a symbol of colonial domination.

The third whimper came a year later. A handful of poorly trained Tientsin British Special Police were left to defend the city’s remaining foreign residents, numbering approximately 750 resident enemies of Japan. Many of the French had gone “Vichy;” the Germans and Italians were allied with Japan; the White Russians and Jews in Tientsin were predominantly stateless, having few enemies and even fewer friends.

Bird’s eye view of Tientsin withGordon Hall standing proud center – top – with Victoria Park spread out in foreground, Victoria Road on right, Astor Hotel on far right. Gordon Hall, built in 1890 in commemoration of General Charles Gordon, was torn down due to damage after the 1976 Tangshan Earthquake. Date of picture unknown – online sources

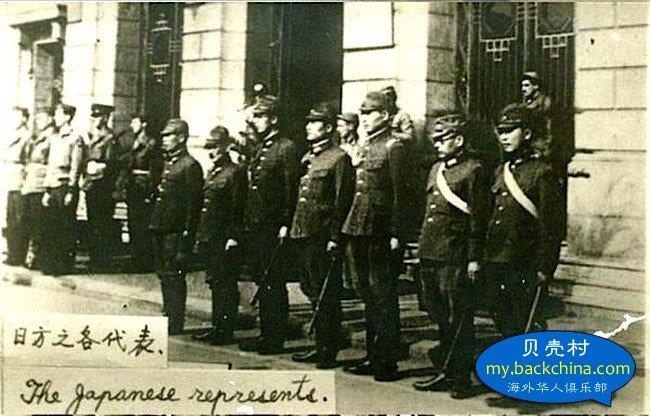

To avoid bloodshed, ammunition was confiscated, according to Power. His thirty-seven-member-group in charge of defending the British Bund had no bullets. On December 8, 1941, which due to the international time difference was the same day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the “Island Dwarfs” – a Chinese derogatory term for Japanese soldiers – also poured into Tientsin’s British Concession.

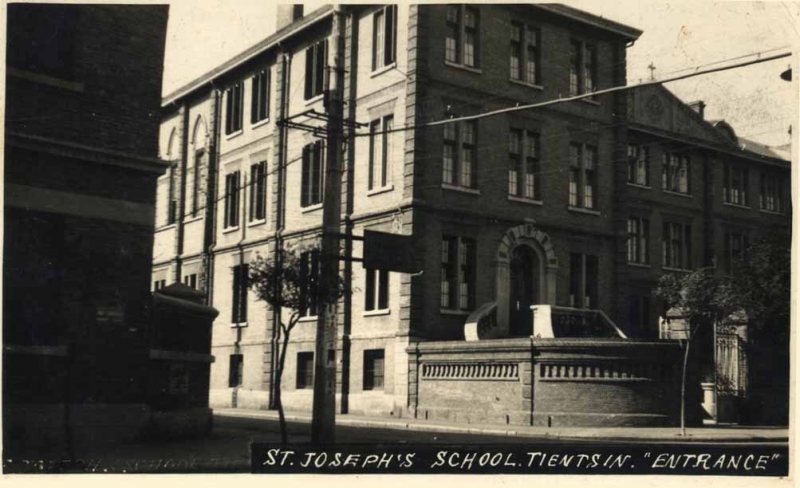

Anne Knüppe-de Jongh was twelve-years-old and a student at St. Joseph’s High School in Tientsin’s French Concession when she was “arrested” by Japanese soldiers.

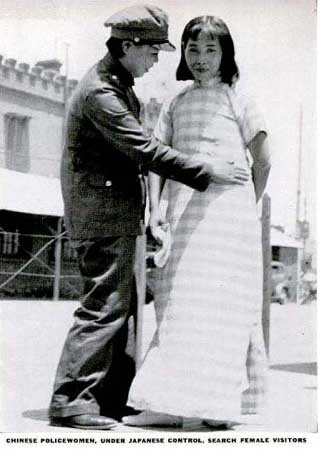

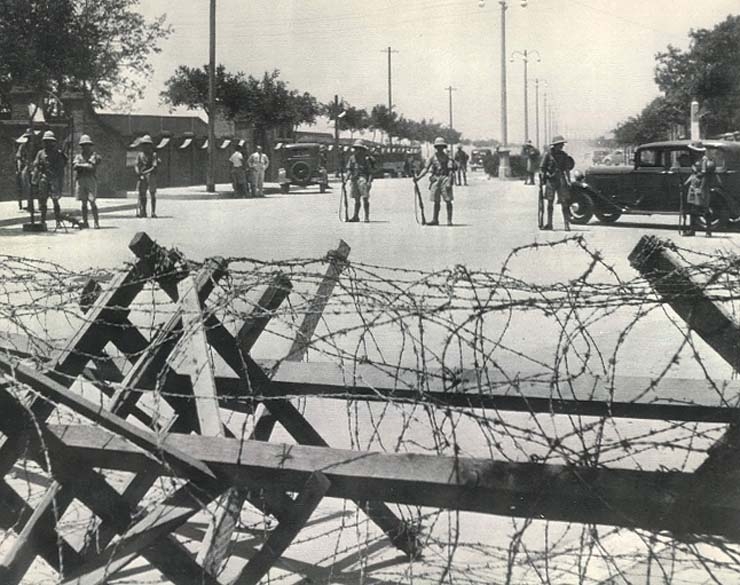

For fifteen months following Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, she lived in fear with her parents and siblings in Tientsin. Being a Dutch citizen, she was forced to wear the identifying red armband. Barbed wire barricades and Japanese soldiers pointing Arisaka rifles separated the concessional areas, making usual routes to school and favorite parks difficult to travel.

“My parents were very troubled,” Knüppe-de Jongh said. “They dreaded an internment.” Her father was a manager for the Holland-China Trading Co.

Before the war began however, her life was filled with pleasant memories, of fancy dress parties, pond skating in winter, playgrounds and horse racing. Every five years her family would travel by sea or by the Siberian Railway home to Europe, and her summers in China were spent vacationing at Peitaiho (Beidaihe). The life her parents provided was of a style no one thought could end, and when the good life was taken, it shattered with the ferocity of a Gobi sand storm.

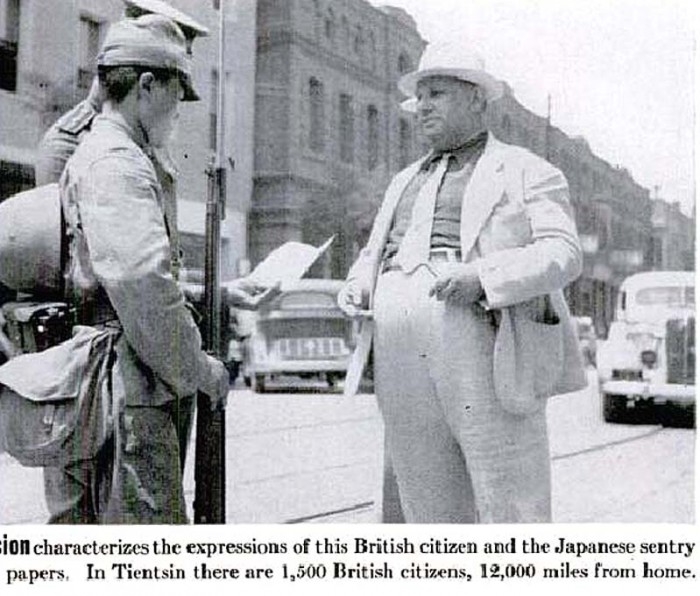

Japanese guard – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

“Just could not get out of the house facing a Japanese machine gun,” Ron Bridge, an Englishman, said. Bridge was born into the British Concession at Tientsin. His family’s history in China dates to 1885, when his grandfather Albert Henry Bridge acted as an interpreter during the post Boxer Uprising negotiations in 1900. “Movement was restricted with night curfew, but one could walk about with a red armband in Tientsin.” His father and uncle were directors of Pottinger & Co., among other projects a real estate company established in the late nineteenth century. Being bilingual he knew the red armband was also a symbol of bravery, or “elite,” which “really got up the Japanese noses,” he said.

Mary Previte, who is now an American and a noted speaker on life as a child during World War II in China, was from Chefoo, known today as Yantai. With warring armies separating her and her siblings from her parents, she was taken from school along with nearly three hundred other classmates and interned at Chefoo before being sent to the Courtyard of the Happy Way in Weihsien, now Weifang, Shandong Province. In Weihsien, she said, all internees were required to wear cloth badges with a prisoner number. She did not see her parents until after the Japanese surrender and spoke of her experiences at the Sixtieth Anniversary celebration of the Weihsien Concentration Camp on August 17, 2005.

“They brought a Shinto priest to the ball field of our school,” Previte said. “He conducted a ceremony that said our school now belonged to the Great Emperor of Japan. They pasted paper seals on the furniture, seals on the pianos, seals on the equipment – Japanese writing that said all this now belonged to the Great Emperor of Japan. Then they put seals on us – armbands.

“We belonged to the Emperor, too.”

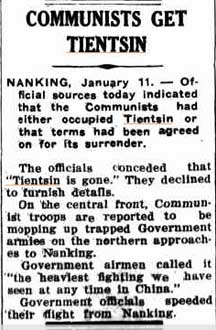

The noose tightened. Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere began with blitzkrieg speed at Pearl Harbor, simultaneously spreading south over Asia’s islands and west across China’s provinces. Tientsin’s foreign residents were named “enemies of Japan” and were issued letters from Japanese authorities stating they would soon be relocated to Civil Internment Centers, where “every comfort of Western culture will be yours.”

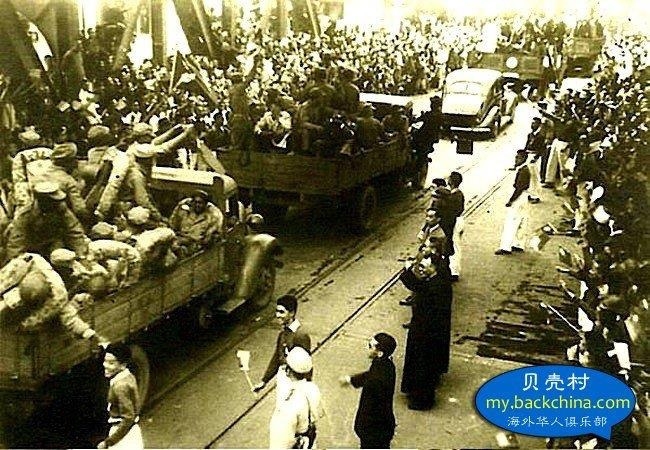

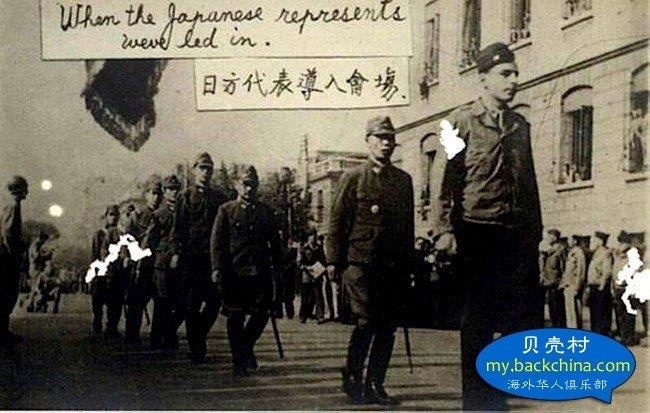

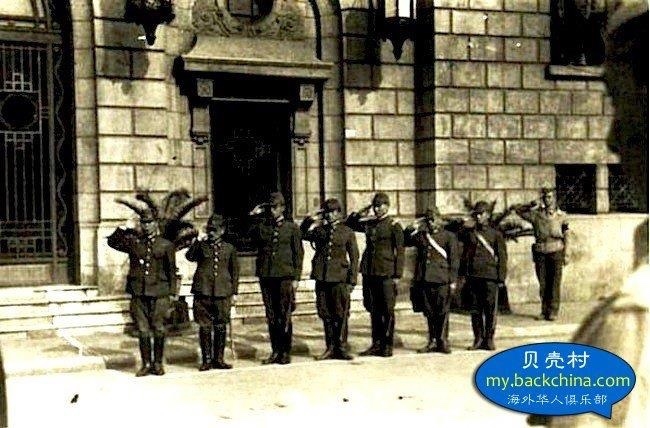

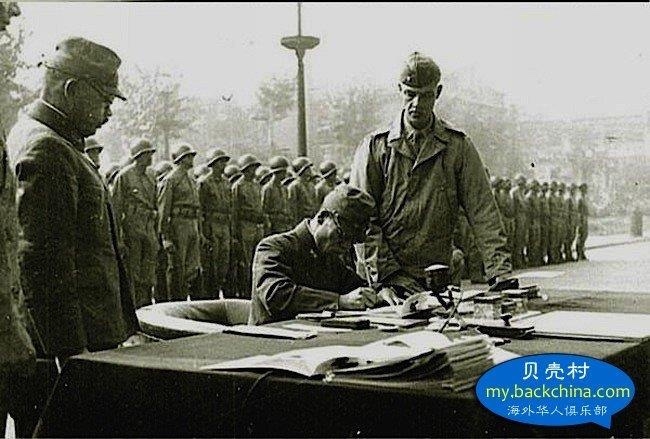

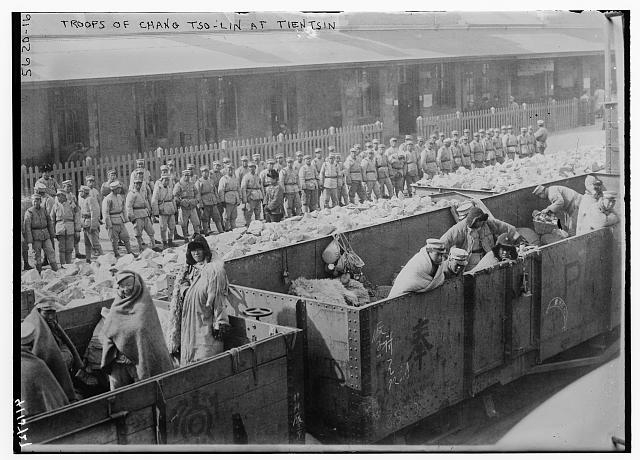

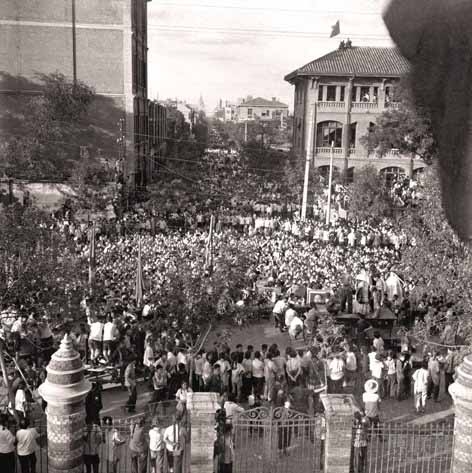

By March 1943, the enemies of Japan, which included Great Britain, Australia, Greece, the Dutch, Norwegian, Spanish, Danish, the United States and more, were paraded from places such as Victoria Park and the Volunteer Headquarters down Victoria Road to Tientsin’s East Train Station.

Bridge was only a boy of nine years when he became an enemy of Japan and was sent to the Courtyard of the Happy Way. His walk from home to Tientsin’s East Train Station was pushing a baby buggy stuffed with food tins with his baby brother perched precariously on the top.

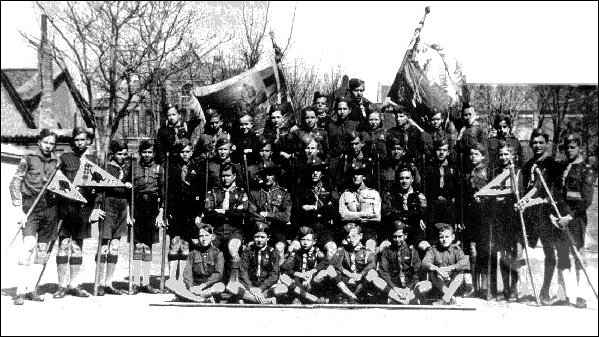

A handful of the children of Weihsien around the time of incarceration

“Among those being jostled about by the arrogant Japanese were agents for large American oil, auto, and tobacco companies, British shipping magnates, and representative of banks of all nations, who traded in the Far East for a century,” Pamela Masters wrote in her autobiography The Mushroom Years. Although Masters was not born in Tientsin, her family had lived and worked in China for three generations, and frequently made trips to the troubled metropolis.

Everyone, Masters wrote, from the youngest infant to the oldest shipping magnate, wore the “demeaning” red arm band, with the character 英 (ying), the symbol for England, which ironically also means hero, emblazoned for all to see.

Despite the incessant turmoil in Tientsin before World War II, not one local Tientsiner cheered the foreign exodus while they were marched at gunpoint to the train station. Third class carriages waited to transport all enemies of Japan to concentration camps, known as “civil assembly centers.” Masters remembered her family’s coolie servant, named Jung-ya, running up and offering to carry their heavy suitcases.

“They [Master’s parents] smiled their thanks, and without thinking, handed their suitcases over to him. A soldier rushed up out of nowhere and hit Jung-ya across the head with his rifle butt. As he fell to the ground, the guard snatched the two cases from his unresisting hands and shoved them at Mother and Dad, shouting and waving his rifle and stamping his foot.

“The message was clear to all who witnessed the incident.”

Most of Tientsin’s foreign enemies, including other foreigners from Peking and Chefoo, were sent to Weihsien’s Courtyard of the Happy Way.

Before the Japanese takeover of Tientsin’s concessions, Power was entrained to Shanghai along with consular staff and high end company officers and their families for repatriation on the prisoner exchange ship Kamakura Maruwas, but he landed in Shanghai’s Pootung Camp, a tobacco godown, or warehouse, before being herded to the Lunghua Civil Assembly Center. He was later transferred north to Weihsien, where he was reunited with his family and 1,540 other internees.

While en route to his first prison, Power walked the “White Man’s ultimate humiliation” along the wide esplanades of the Far East’s banking capital. Japanese strategists declared themselves saviors of China for ridding the cities of “Roundeyes,” and Japanese soldiers fully expected the Chinese to ridicule the Western prisoners along the way.

Not one Chinese uttered a single insult, Power wrote. Despite repeated attempts to banish the foreigner from their country, Chinese onlookers were strangely quiet.

“No insults thrown, no jeers, no catcalls. A sea of silent poker faces saw us onto the waiting tender.”

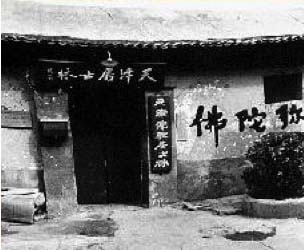

Courtyard of the Happy Way as it around the time of World War II – China Daily

WEIHSIEN, CHINA – Great Britain’s Asian colonies fell like dominoes, spurring a sense of failure in some colonialist men, overturning their self-image of the dynamic, colonial, indefatigable male. According to one account written by Bernice Archer called The Internment of Western Civilians Under the Japanese 1941-1945, many Western men at the onslaught of World War II were demoralized.

“There we were literally reduced to our bare selves. We no longer had about us the aura of our offices, our clerks and tambies, our cars and comfortable homes and servants. All the trappings of our Western civilizations had been ruthlessly shorn from us. We were prisoners and nothing more.”

Women prisoners, according to Archer, were expected to share the same corporate and patriotic loyalties as their husbands. When they married a colonial man, they married his job as well, and were expected to play their designated roles no matter the costs. Chins up, shoulders back, “be calm and carry on,” even while walking straight into internment.

Courtyard of the Happy Way 樂道院 (le dao yuan) – picture and corresponding map – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

“This was a prison.”

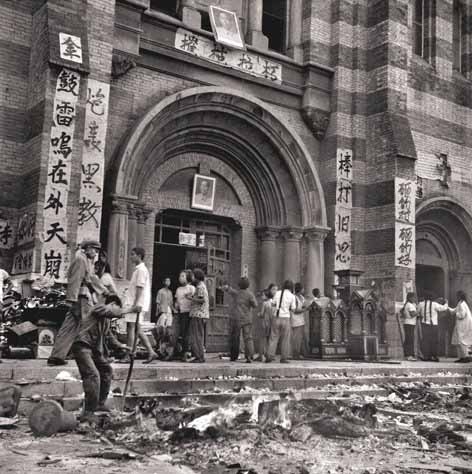

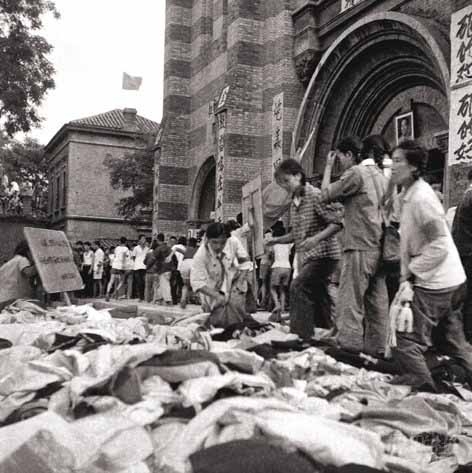

Tientsin’s foreigners were crammed into trains, herded south through war torn fields, then marched into a grey brick walled prison – the Courtyard of the Happy Way – lined up on an athletic field next to a church for roll call.

Through the eyes and diary of David Treadup, a former internee, John Hersey wrote in his book The Call: “I was listless, tired, downhearted, in pain, but that wall roused me. My buttocks prickled at the sight of it. It was as if I were in an old wooden house and waked up from a deep sleep smelling smoke. This was the usual eight-foot gray brick mission compound wall, familiar to me as an often seen boundary of refuge for foreigners, setting the limits of a peaceful sanctuary form the Chinese universe roundabout – except that now there was a difference: guard turrets had been erected at the corners of the wall. This was no refuge. This was a prison.”

Out of the twelve Japanese internment camps holding foreigners in Mainland China, the Weihsien Civil Assembly Center was one of the largest. The internment camp was originally built by American Protestant missionaries in 1924, and requisitioned by Japanese military and consular officials as a camp to hold foreign enemies in 1943. The prison’s commandant was Mister Izu; the prison’s captain was known by children as “King Kong,” who passed on most of his duties to his aide, a wiry and obnoxious man nicknamed “Gold Tooth.” The Courtyard of the Happy Way became a propaganda showpiece, Japan’s idyllic centerfold, featuring electrified wire and an encircling stone wall, manned gun towers, rows of cells for internees to live, coal-burning kitchens, eighteen Chinese-styled squatty potties and forty Western-styled toilets, all of which drained into cesspools.

“This place, they knew and could see, was a former missionary compound,” Hersey wrote. “Now all was drab and befouled. Most of the passageways were cluttered with all sorts of furniture and trash thrown out from the buildings, presumably by uncaring bivouacs of Japanese troops and, later, by quartermasters in hasty preparations to receive these internees.”

The Japanese had not made any arrangements for a hospital, but they were proud of the fine job internees created out of rubble. They photographed Weihsien, according to internees, and sent the pictures across the world as propaganda showing how well they were treating the prisoners.

Most internees worked diligently at their assigned tasks, some rose before dawn to stoke kitchen fires; Catholic nuns volunteered for latrine duties. Management fell to the internees, as the Japanese wanted little to do with their prisoners.

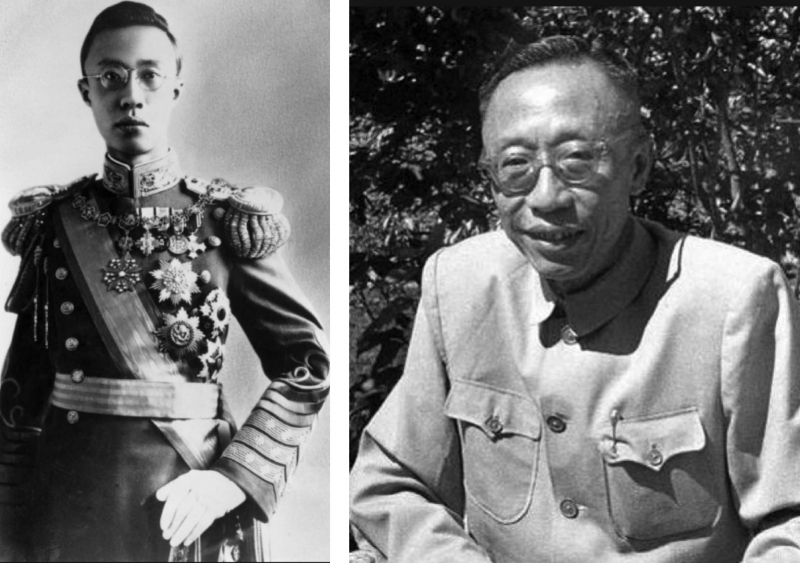

Canadian citizen Angela Cox Elliott was born in the Courtyard of the Happy Way, and although too young to remember many details, she returned in 2005 to visit her birthplace for the first time since 1945. Her father, George Edward Cox, was the prison camp’s tinsmith and a friend of the Power’s family. Before incarceration he was a graduate of Tientsin’s St. Louis College and a secretary at Credit Foncier de l’Extreme Orient. He also served with Power in the Tientsin Volunteer Defense Corps. Elliott’s mother, Philomena Splingaerd, half Chinese, half Belgian, was one of many granddaughters of Paul Splingaerd, the “Belgian Mandarin,” who was knighted by Belgian’s King Leopold II and raised to the ninth level of Mandarin by the Qing Imperial Court.

Elliott was born in the camp’s hospital, which had already been ransacked for supplies before the internees arrived. Leftover hospital equipment was pieced together. Doctors learned to improvise. Requests for supplies were never fully granted; medicines trickled in at a snail’s pace.

Elliott remembers Japanese guards treating her kindly, as they did most children.

“The Jap soldiers may not have been that kind to other children, but I looked somewhat Japanese or Asian,” Elliott said. “They more or less left people alone. My ma said that a Japanese soldier used to come by and liked to play with me, probably reminded him of his kids as I am so Asian looking.”

Many adults, however, were not treated with such kindness. According to an “I Remember” post in Weihsien-Paintings, a new father was beaten for the name he chose to give his newborn son.

“At Weihsien whilst his wife was actually giving birth to their child, Japanese guards barged right into the delivery room and demanded the name of the child to transmit to Tokyo. [He] replied that until the child was born he couldn’t tell whether it was a boy or a girl. He told them that if it was a boy, he would name him Arthur in honor of General MacArthur. This enraged the guards and they beat him in front of my eyes. They beat him three times.”

Local Chinese farmers were also frequently beaten or tortured, sometimes shot for minor offenses.

The camp was approximately 49,000 square meters, and held at one time or another more than 2,250 internees. It also held an assembly hall, formerly a church, used by all denominations, a small baseball field, which was used to play softball after too many balls sailed over the wall, a large bell by Block 23, which was off limits to internees. Cobbled lanes were given names, such as “Lovers Lane” and “Tin Pan Alley.”

Roll call was mandated one to two times a day, according to some former internees.

Clean water was one of the camp’s most significant problems.

“Water was a problem at Weihsien,” Bridge said. “The wells were often within ten yards of the cesspits.” His family, including two adults and two children, were initially given one room, twelve feet by eight feet, in which to live. Communal meals consisted of vegetable scraps, potatoes, turnips, soybeans, millet and Indian corn, and rarely rice.

Food was scarce, especially toward the end of the war. “Of course there was that horrible hungry feeling, that had to be covered by kaoliang [sorghum] porridges and thin soups,” Knüppe-de Jongh said. Her family had arranged with a Swiss friend to be sent parcels several times a year, which included smoked bacon, lard, egg powder and other food products. “I remember my mother baking a kind of omelet from egg powder with chips of bacon and it tasted really delicious, in my memory.” Her brother, Paul, who was also born three months after arriving at the camp, was undernourished, weak and small for his age.

Meals consisted mainly of sorghum breakfasts, thin turnip soups with precious little meat called S.O.S. or “same old soup” for lunch. Occasionally horse meat was on the menu. Vegetables and eggs were worth their weight in gold when the black market ran unhindered, but obtained only with money or by trade. The internees’ savior was bread, baked daily by George Wallis and his kitchen crew, which kept starvation from becomming acute.

“I remember the Menu Board on which the cooks used their creative writing skills to describe the coming meal in the most exotic terms,” said a former inmate in the “I Remember” section of Weihsien-Paintings website. “You would think that you were in the grandest hotel in the land. What was actually served was bread porridge for breakfast, watery stew in the middle of the day, and whatever was left over for the evening meal.”

Weevils and crushed eggshells became important sources of protein and calcium. Ted Pearson, who was seven-years-old when he was imprisoned, had lived at Villa Jeanne d’Arc, off Racecourse Road on the way to Tientsin’s Country Club. “The camp committee decided that to prevent rickets the children should get powdered eggshells, one tablespoon for each child. All eggshells were saved for this purpose. I know I never got rickets.”

The Japanese guards through children’s eyes were not seen as objects of hate, but of ridicule. Janette Ley Pander, who formerly lived at the Belgian Bank on Victoria Road in Tientsin, was four when she arrived at the camp. “We were very ‘lucky’ in Weihsien to have been held in Northern China-Japanese Territory, and kept by consular police as well as the military. In my memory King Kong Bushido was a laugh, a kind of bogey man. Of course the Japanese were our captors and we felt that very well, but many were very kind in a personal way. After all, we were all stuck in the middle of nowhere with the Chinese civil war surrounding us. I only felt the danger of our situation through my parents’ angst.”

With approximately 2,500 internees waiting lines became inevitable. There were lines for the toilets, chow lines and lines for lukewarm showers. The winters were bone-rattling cold; summers were hot and humid. Every capable person was assigned chores. A discipline committee headed in part by former Tientsin Municipal Police Chief Inspector P.J. Lawless and Ted McLaren was organized, and punishments were unique to the environment. Once, according to Hersey, Treadup was sentenced to make two circles of the camp wearing a sign saying “I Am a Thief” around his neck after stealing a piece of meat.

“The Morning Water Queue” drawing at Weihsien by William A. Smith, an OSS officer – special courtesy and thanks to the family of William A. Smith, Weihsien-Paintings and the OSS Museum Collection

In the Courtyard of the Happy Way, trading taipans lived next to hooligans, former prostitutes and drug addicts alongside Catholics and Protestants. Single men and women had their own dormitories; families were put into thirteen feet by eight feet cells. Hersey offers a unique description of Treadup’s roommates in the single men’s dormitory.

“A potbellied retired sergeant of the U.S. Fifteenth Infantry Regiment in Tientsin, a bully by nature and training; he had lived a shady life in the French Concession there, some said as a middleman in sales of smuggled curios.

Food distribution at Weihsien – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

“An Englishman with startling mustaches like porcupine quills, a grand personage high up in Kailan Mining, owner in Tientsin of the great racehorse Kettledrum, which had won the Tientsin Champion Stakes five straight years.

“An American derelict, formerly a Socony engineer, whose “better years,” he told everyone, had been in the Bahrein oil fields in the Persian Gulf, now a lank, gaunt sausage of a man suffering agonizing cramps and sweats in forced withdrawal from his beloved paikar, [lao bai gar] the fiery Chinese liquor.

“A muscular American Negro dance instructor from the Voytenko Dancing School in Tientsin.

“A Eurasian, half Belgian and half Chinese, a salesman of cameras in a Tientsin store, who looked and acted like a ravishingly beautiful woman.

“A Pentecostal missionary, a bachelor with rattling dry bones under leathery dry skin, a kindly but rather repugnant man, with little dark velvety bags like bat bellies under his eyes, who groaned and babbled hair-raising fragments of sermons in his sleep ― bringing loud roars for silence from the sergeant and the dancer.

“An English executive of Whiteaway Laidlaw, the largest department store in the British Concession, a sensible, direct, practical, unemotional man, an observer of rules and a mediator in all storms in the room.

“The former chief steward of the posh Tientsin Club, who still wore the black coat, double-breasted gray waistcoat, and striped trousers of his Club uniform, all of which he somehow kept impeccably clean, a straight-backed figure, honorable and correct, yet also mischievous, a fountain of laughter, a man, as David soon wrote, “too good to be true.”

“A mean little Australian errand runner for the Customs Service, with a fake limp, who told a new lie every day about imaginary past glories ― as the pilot of a smuggling plane, as a photographer of nude women, as a big-time Shanghai gambler ― reduced now to a finicky, sneaky, sniveling complainer, scornful of Americans whatever their station but embarrassingly obsequious to upper-class Englishmen.”

Helen Burton, a North Dakota native, reading the letter notifying her of her brother’s death, taken by Life Magazine

One woman at Weihsien, Helen Burton, a North Dakota native, had been the proprietor of the Camels Bell curios and candy shop in Peking before incarceration. At the Courtyard of the Happy Way she started a bartering shack, called the White Elephant’s Bell, for goods to be exchanged, including one instance of a luxurious fur coat for jam. Months with no sugar can have a depreciating effect on luxury goods. She was a socialite, always keeping busy, adopted four Chinese girls before imprisonment, and never married. A photograph of Burton reading a letter about the death of her brother for the first time was featured in Life Magazine after liberation.

Surprisingly, according to all Weihsien survivors, few incidents occurred between the internees.

Suicide attempts, however, were not uncommon.

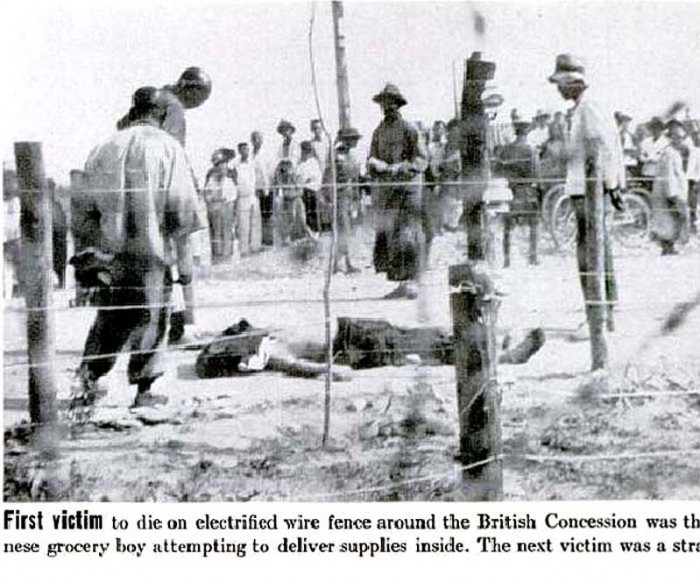

“Looking back on all the attempted suicides, there seemed to be a common denominator: each person had, at some time, been a “somebody” in a once exciting world,” wrote Masters, who admits in her book she once came close to grabbing the electric wire surrounding the camp, which would have killed her. A Catholic priest rescued her. One Chefoo schoolboy however, was killed by accidentally touching the wire.

“The woman who swallowed the box of match heads had been a famous fashion model in the States back in the thirties. She was still very beautiful, with a doting husband – and no children, as she didn’t want to ruin her figure. She was living in the past and couldn’t stand the anonymity of being just another lost soul in the prison camp.

“The girl who slashed her wrists was also extremely beautiful. Her mother had been the most famous madame in Peking, and she the toast of the nightlife of that cosmopolitan city.”

One of the most mind-boggling events during the war years at the prison was when the American Red Cross sent a shipment of foodstuffs to the camp, which the Japanese allowed. A handful of American missionaries, however, became indignant when they discovered the packages were to be handed out to each internee, saying the packages were from America and therefore meant for Americans only.

“Afraid of an uprising, the Commandant took immediate control and had all the parcels locked up until he got instructions from Tokyo. While we waited for them, the camp that had once been tolerant of all the different nationals became bitterly divided.”

Even after Tokyo’s instructions to distribute one Red Cross package to each internee, regardless of nationality, the American missionary family, fat and slovenly and known as the Hattons in Masters’ book, threw themselves upon the parcels and wailed, “We want our due!”

Other missionaries, such as 1924 Olympic champion Eric Liddell were invaluable to the internees’ moral. Liddell who was born in Tientsin is said by some Chinese to be

Eric Liddell, before the war, at right – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

China’s first Olympic gold medalist, but was most famously known as the athlete who refused to run on Sunday. He was a soft-spoken, bald, Scottish missionary, who never talked about his past successes in sports, both track and rugby, and wore a permanent smile. He lived in Block 23, Room 8 at the Courtyard of the Happy Way, and according to Power was the most respected man in camp. Liddell also taught mathematics, gave sermons and was known for his sense of humor. His running shoes, shortly before his death due to a brain tumor, were given away to fellow inmate Stephen A. Metcalf who helped Liddell with the camp’s recreation committee.

“During the following years it was my privilege to help Eric in his work on the recreation committee,” Metcalf wrote in his story about Liddell entitled Eric Liddel A Man Who Could Forgive. He repaired the prison’s obsolete sporting equipment with thin sticks of Chinese black glue made from horse hoofs.

“He was always so enthusiastic and never thought of it as a sacrifice to tear up his sheets to bind up old bats and hockey sticks etc. Even some of his trophies were sold on the black market to help the suffering. As the years passed, we were all suffering in one way or another, and the tremendous workload he took on himself began to take its toll.

Eric Liddell’s room – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

“About three weeks before Eric began to succumb to the brain tumor he came up to me with his pair of dilapidated running shoes. They were all patched and sewn up with string. In a shy and almost offhand manner, he said, ‘Steve, I see your shoes are worn out and it is now midwinter. Perhaps you will be able to get a few weeks of wear out of these.’ Then, with a knowing nod, he pressed them into my hand.”

Months later, due to necessity, Metcalf traded the shoes for a pair of US Army boots.

According to an “I Remember” report in the Weihsien-Paintings website, a young internee at the time remembered Liddell’s burial service.

“I remember that grey winter day, when a bedraggled procession of children in threadbare, outgrown overcoats followed the coffin of our beloved “Uncle Eric” to the small camp graveyard. Our legs were bear in the bitter cold; our woolen stockings were the first things to wear out, and trousers were not part of our wardrobe in those days… As we followed the pallbearers on the frozen ground, one of them, my brother Norman Cliff, the cheap coffin creaked and groaned: would it hold together until they reached the grave? It did, and no one else knew of their distress.”

Eric Liddell’s grave – courtesy of Weihsien-paintings

Tientsin native, Yu Wenji, now eighty-six-years old, was Liddell’s ball boy when he played tennis before incarceration, the China Daily reported on August 12, 2012. Yu attended Liddell’s English classes and also Liddell’s sermons at Tientsin’s All Saint’s Church.

“He had the chance to leave for Canada with his pregnant wife and two children, but he refused to leave his brothers in church behind. I guess that must have been a tough decision for him,” Yu said.

Yu wept openly, he said, when he heard the Chariots of Fire theme song during the London Olympics in 2012, and has spent fifteen years writing a biography of Liddell. “I watched the movie three times in a row when I first got the videotape,” he said. “He always leaned back his head when crossing the finishing line. That scene is still vivid in my mind.”

When asked about his goals for his book on Eric Liddell, Yu, who is almost blind, said his memories of that time will never fade.

“I don’t want fame or money, I am eighty-six,” Yu said. “I just want to show that Liddell is a good example of someone who can erase misunderstanding between China and Western countries.”

Liddell, along with at least thirty-one other Weihsien internees, died and was buried in the Courtyard of the Happy Way. A Japanese soldier, according to the China Daily, secretly preserved Liddell’s death certificate when he was ordered to destroy all evidence. Despite the city’s recent renovations, a red marble memorial stone in memory of Liddell still remains inside the Courtyard of the Happy Way.

Escape

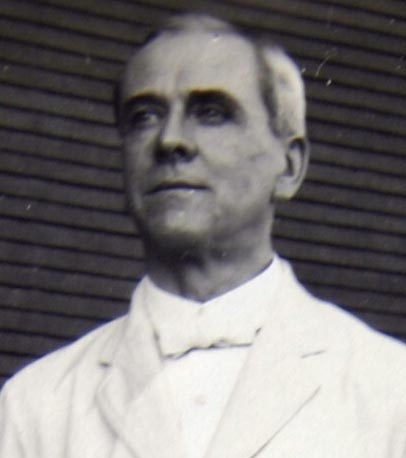

Laurance Tipton in 1988 – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

Laurance Tipton, a British businessman, distributed cigarettes by camel caravan to China’s northwest before his incarceration at the Courtyard of the Happy Way. He wrote a book entitled Chinese Escapade, published in 1949, about the loss of his business, which took him to Peking, Tientsin, Mongolia and elsewhere, his escape from prison and the months he spent fighting alongside Chinese guerillas.

Tipton was a kitchen fire stoker during his time at the Courtyard of the Happy Way.

“For the first few weeks it was exhausting work but one gradually got used to it. I first worked in the Peking kitchen as general help and then graduated to the butchery, where the maggot-ridden carcasses and the myriads of flies which laid eggs on the meat faster than one could wipe them off were rather more than I could stomach.”

Internees, Tipton wrote, saw little of Mister Izu, the camp’s commandant, or his staff, as management was left mostly in the hands of a foreign committee. Complaints and requests were passed through the committee and to the commandant.

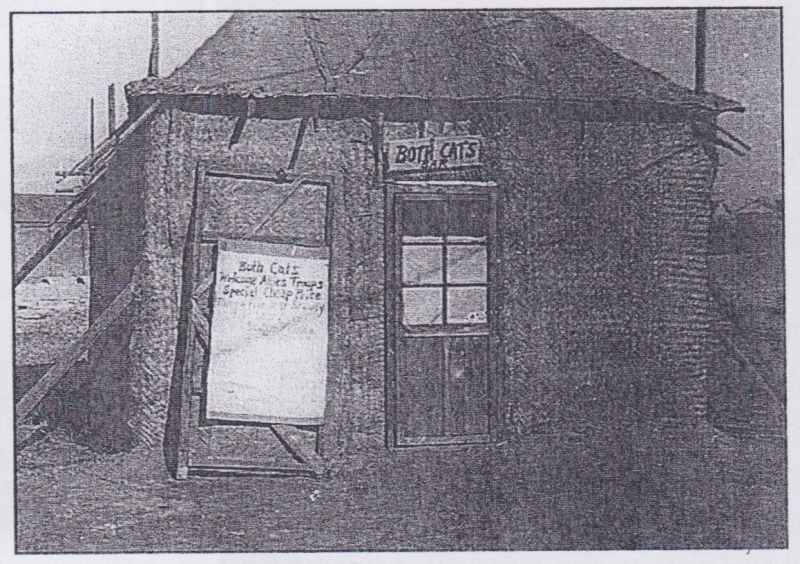

A black market with local Chinese on the other side of the prison wall began two weeks after his arrival. “The Catholic Fathers were the first to operate on a large and well-organized scale,” Tipton wrote. “It was merely a matter of finding a convenient spot out of the sentry’s view, a few words of hasty bargaining, throwing a rope and hauling up a basket of fresh country eggs.”

Outside, regular bootlegging gangs were organized: the Hans, the Chaos and the Wangs. “In the dead of night they would send a representative over. Greased and clad only in a G-string, he would slip in, take the orders, “shroff” over the accounts, receive payment and quietly disappear. Transactions were made through a drainage hole along the wall.

In the thirty-third year of the Republic of China, a letter written by Wang Yu-min, of the Fourth Mobile Column of the Shantung-Kiangsu War Area, was snuck into the prison.

“My division is able to rescue you, snatching you from the tiger’s mouth…” a part of the letter said. “We can well imagine that your life in Hades must reach the limits of inhuman cruelty.”

With continued correspondence, an escape plan formed. Tipton asked Arthur Hummel to accompany. On June 8, 1943, around 8:30 at night, Tipton and Hummel waited until the changing of the guards, scaled a guard tower and dropped over the side of the wall. They hid in a graveyard fifty yards away.

“A pause to collect our breath, and we made another dash which took us out of range of the searchlights, and, taking our bearings from the camp, we headed directly north over ploughed fields, through wheat crops, stumbling over ditches and sunken roads until we reached the stream that flowed north of the camp. Wading across this, we headed in the direction of the cemetery.”

Members of the Fourth Mobile Column of the Shantung-Kiangsu War Area found them, and after saying the password “Friends,” unrolled a triangular white cloth that said ‘Welcome the British and American Representative! Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!’

Tipton and Hummel spent the next two years fighting alongside the guerillas, informed Western military authorities of the camp’s troubles, and returned to the camp as internees after liberation.

Internees were spared repercussions when the committee promised the commandant not to attempt escapes again if the commandant provided an X-ray machine from a nearby city.

Entertainment

Not everything at the Courtyard of the Happy Way was dismal. Many children who survived look back on their incarceration with fond memories. Boredom, to adolescents, was an enemy more incipient than their Japanese guards.

Internee Earl West formed a jazz band. He had been a Tientsin musical star before incarceration, playing at a nightclub called the Little Club, according to Power. The band, comprised of black musicians, performed most Friday nights inside one of the prison’s kitchens.

“What a boon those dances were for the romantically inclined, especially among the shy!” Power wrote. “Many a couple’s relationship started at a dance, some leading to marriage.”

“I certainly enjoyed the dances in Kitchen Number 1,” Knüppe-de Jongh said. “We had some fine bands. I did more watching with my friends than really dancing, I’m afraid, being thirteen or fourteen years old, but I had fun there and occasionally I had a younger partner to dance with – but it was all very exciting for a teenager.”

Brigadier Len Stranks formed the Salvation Army Band, which played at sporting events and church services and on occasion the outlawed Star Spangled Banner.

Mclaren, of the discipline committee, built a secret radio the Japanese never found. He was also privy to Tipton and Hummel’s escape, and organized an ‘underground police’ force of reliable, able-bodied internees, ready to take control of the camp if the opportunity arose.

The black market over the compound’s wall was kept alive for the duration of the war, despite Japanese intentions of either controlling or stopping the secret trades. At least two Chinese farmers were killed by firing squad when caught. Internees heard the rifle shots.

A Trappist monk named Father Scanlan had a foolproof method for receiving eggs undetected. His order lifted the strict rules against speaking so the monks would be able to work with internees. From a far corner of the wall he pried loose a few bricks and would pull eggs through the hole, in trade with a Chinese farmer. If a guard happened along, two Trappist monks down the line would begin a Gregorian chant and Father Scanlan would quickly cover the eggs with his long monk’s robe, squatting protectively like a mother hen. After four months he was caught, according to Langdon Gilkey in his book Shantung Compound, when a guard lifted his robe and discovered 150 eggs. Although Japanese guards held the bushy-bearded monks to some degree of respect, egg laying was not among their “holy powers.”

“Father Darby [Scanlon, name changed in Gilkey’s book] was whisked off to the guardhouse,” Gilkey wrote. “The first trial of camp life began. The camp awaited the outcome of the trial with bated breath; we were all fearful that the charming Trappist might be shot or at best tortured. For two days, the chief of police reviewed all the evidence on the charge of black marketeering, which was, to say the least, conclusive.”

The commandant sentenced Father Scanlon to one and a half months of solitary confinement.

“The Japanese looked baffled when the camp greeted this news with a howl of delight, and shook their heads wonderingly as the little Trappist monk was led off to his new cell joyously singing.”

Drawing made by a Weihsien internee of the black market – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

Throughout the duration of imprisonment there were others not of the cloth and not accustomed to long months of silence who were caught and also sentenced to solitary confinement. During these times dozens of internees volunteered their own private stashes of food and endangered their own lives to sneak carefully-hoarded provisions into the lonely prisoners. Such as the case of Peter Fox, who rang the prison bell in celebration after hearing the good news of Nazi Germany’s surrender over the homemade radio. The entire camp went joyfully without rations for a week before he turned himself in.

Some vices continued, such as trading for Chinese “bai gar” liquor, and at least one Russian woman opened her bed as a brothel in trade for food or money.

During the warmer months the recreation committee, led by Eric Liddell, held softball matches and track events.

“The ball games were a big part of our lives and we had a girls team and we played against the younger boys,” Chefoo School student Maida Campbell Harris said. “We hung out at all the ball games and for myself I think I was in an adolescent dream world rather than being aware of the danger around us.”

Many young internees learned new card games or played marbles, hopscotch and jump rope, while the more adventurous young held rat, bedbug and fly catching contests. According to an “I Remember” report in the Weihsien-Paintings website, a young boy and a Chefoo School student named James H. Taylor III won the fly catching contest with a count of 3,500 neatly counted flies in a bottle.

“The winner got a rat’s skull,” Pearson said. “The rat’s skull was amazing as the lower fangs curled right over it’s head. I remember it clearly.” Besides softball games and dances, he remembers drawing classes and plays that his father acted in, such as Androcles and the Lion. There were also ballet shows, oratorios such as as Handel’s Messiah, mostly led by a man named Percy Gleed, and Tchiakowsky’s Swan Lake. Catholic children had their first communions inside the camp. Brave young boys made daring trips into the “out of bounds” Japanese area to steal coal and sugar from under their captors’ noses. Pearson’s first crush fell on a young girl named Henrietta, whose mother fried cheese sandwiches when they had the makings. “It was like manna from heaven,” Pearson said.

B — is for BRITISH:

James H. Taylor, III, wears the armband required for prisoners of the Japanese in Chefoo (now called Yantai), Shandong Province, China. Immediately after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, the Japanese commandeered the Chefoo School and its students and immediately required that when any “enemy alien” left the school campus he must wear an armband that included a large black letter to indicate his or her nationality — B or British, A for American, etc. Taylor was a 12-year-old student when the Japanese took over the Chefoo School. – courtesy of Mary Previte

School continued for most of the prison’s children. Few left the camp behind in their studies. Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, Cub Scouts and Brownies clubs also were formed. Although limited to short hikes, children practiced Morse Code, knot tying. They made various badges like hiking badges, singing badges and naturalist badges. When children turned fifteen, they were allowed to work.

“I turned fifteen in June 1945 and that was when you got a camp job,” Harris said. “Believe it or not I was very keen to have a job. Mine was washing dishes. I worked at Kitchen Two. It was the summer of 1945 and two or three of us had a bowl of water on a table outside – I don’t think there was any soap in it and we had a kind of dish mop and people lined up to have their dishes washed in greasy water. I was so proud of having a job. I guess it was like a fifteen-year-old getting a job at McDonalds today.”

Like most teenagers, Harris became interested in boys.

“I know I was getting very interested in boys like my classmates were and we always knew when the boys we liked were on pumping duty,” Harris said. “We liked the Weihsien boys rather than the Chefoo ones and the Chefoo boys liked the Weihsien girls. I remember we would walk around the camp hoping to see the boy you liked.” She found an English boyfriend, Harris said, who left for England after liberation. “We wrote to each other for a while. His parents were Tientsin business people.”

Clothing shredded, but the internees learned to mend. “Since we men have been reduced to the level of Chinese farmers and coolies, we go, as they do, with our bare backs to the sun, and some wear nothing but underwear briefs,” Hersey wrote. “I have joined the brown race. The women wear the most abbreviated ‘sports suits,’ cut to modern bathing suit patterns, and sometimes even more spare. Female beauty (and, alas, ugliness) is being evidenced, in some cases flaunted. Some of the missionary women, who have been most strict in their speech in the past, have suddenly become startlingly immodest in their dress. Is one supposed to look away, or not?”

During the cold Shandong Province winter months, much of the internees’ spare time was spent trying to stay warm in bed and making coal balls, part coal dust from their Japanese guards, part clay and a small amount of water. “We younger girls made a game of carrying the coal buckets,” wrote Previte. “In a long human chain – girl, bucket, girl, bucket, girl, bucket, girl – we hauled the coal dust from the Japanese quarters back to our dormitory, chanting all the way, ‘Many hands make light work.’”

Non-denominational church services were held on Sundays, and although the Protestants wanted to convert the Catholics, and vice versa, anyone was welcome to attend.

Another “I Remember” post in the Weihsien-Paintings website said, “I believe that is why I look back on Weihsien with joy – I believe it molded me and the adults who kept us entertained beautifully and we did not feel like we lacked – we all ate the glop so what difference did it make? I didn’t feel needy or forlorn because there were so many people building us up and keeping us going.”

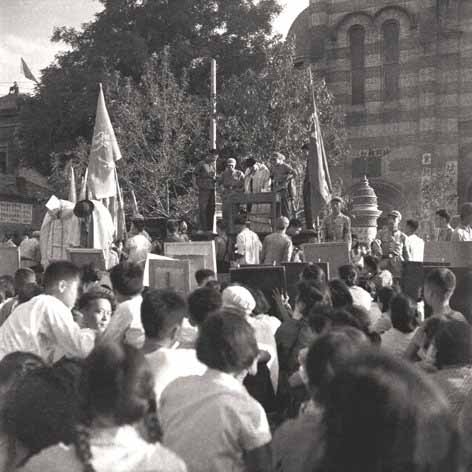

Liberation Day – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

Allied parachute drop over Block 23 of the Courtyard of the Happy Way – special courtesy and thanks to the family of William A. Smith, Weihsien-Paintings and the OSS Museum Collections

Liberation

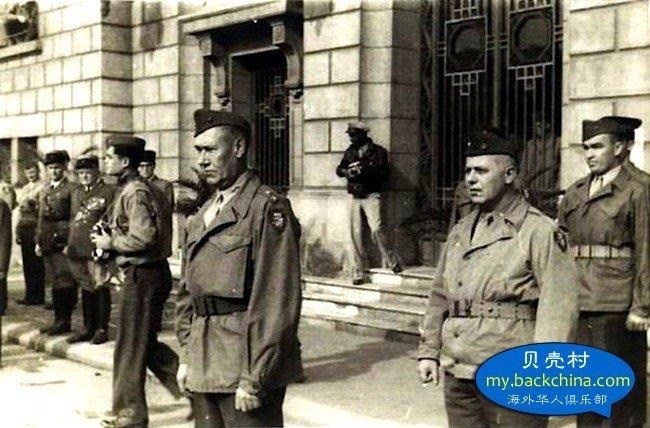

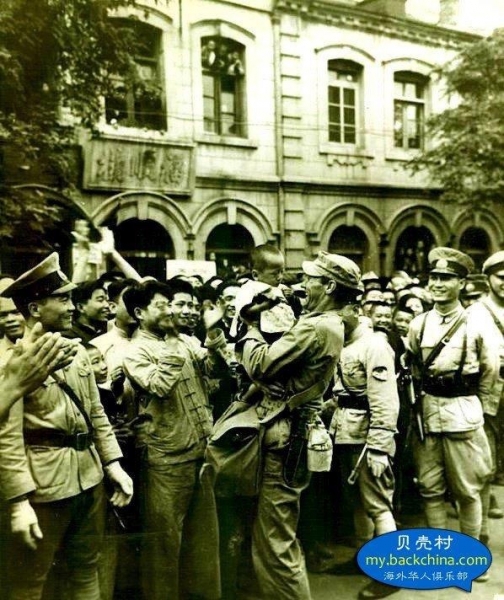

On August 17, 1945, eleven days after atomic “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” devastated Japanese cities, members of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) called the “Duck Team” parachuted into camp. The seven-man team did not know what they were jumping into, or if the Japanese guards were prepared to surrender, but they knew that the Japanese Military Authority had issued orders for all foreign POWs and civilian internees to be exterminated.

According to Doc 2701, Exhibit “O” of the Nara War Crimes Tribunal, the Japanese Army had a policy in place to liquidate all prisoners, by gas, or rifle, or any other available means.

Few commandants, if any, complied. Some defeated officers chose seppuku, ritual suicide, instead. Before Japan’s official surrender the Weihsien guards took to drinking too much saki, and could be heard late into the night singing and wailing their misery at the moon, for no one else cared to listen.

Harris remembered whispers that their lives were about to end. “Mrs Graham our neighbour in Block 57 said we were all being taken out to be shot and it was pretty scary when all the search lights were on and the guards were pushing us around as they were trying to count us. The story was that instead of anyone missing, they counted extras.”

Older internees, such as Power, remembers that just before liberation stress was beginning to show.

James Taylor and Mary Taylor Previte find their names engraved in marble on the monument wall. – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

“A lot of people are getting on edge, some are close to cracking, one for sure has already cracked. He or she is an ax-wielding maniac who has taken to decapitating cats.”

Power kept himself on an even keel for most of his imprisonment, but toward the end of the war his cabin fever got the best of him. He threw a curse at a Japanese sergeant while he was taking roll call.

“Wo tsao ni mama!” Desmond wrote he said.

“He saw me, but I dashed down to my place in the stairwell. Not knowing who the culprit was, he grabbed hold of David Clark, the fifteen-year-old ward of Reverend Simms-Lee and began throttling him. I had no alternative but to present myself as the perpetrator. To this day I can see Bushingdi’s toothy snarl, I can feel the vice like grip on my neck, and I can smell the nap of his black uniform. I was lucky the war was nearly over. My punishment was only several slaps to the face.” The sergeant was nicknamed Bushingdi, meaning “not good” in Chinese, because he was always waving his finger and telling everyone “bu xing, bu xing,” or “no can do.”

Masters was standing in the breakfast chow line when she heard a distant purring noise.

“There was a hush in the chow line as the hum of the plane got louder. It struck me that the sound was different; not the funny, tinny drone of Japanese Zeros and Judys, or the rattling-roar of their bombers, but a strong, steady comforting sound that seemed to push up against the heavens and reverberate back down to earth. I knew instinctively this was one of ours!”

Picture taken by American liberators (William Arthur Smith) end of August or beginning of September 1945. Anne Knüppe-de Jongh is the third on Left, holding brother Frans, looking over camp wall – courtesy Anne Knüppe-de Jongh, and the family of William A. Smith and the OSS Museum Collection

A B-24 Liberator roared over the camp before ejecting OSS officers Major Stanley Staiger, Ensign Jim Moore, Sergeant Tadash Nagaki, Technician Fifth Grade Peter Orlich and Technician Fourth Grade Raymond Hanchulak. Interpreter Edward Wong and US Army First Lieutenant James Hannon also made the jump. With wild jubilation, internees stormed the gateway to the Courtyard of the Happy Way. Japanese soldiers made no effort to resist. Their war was over.

The Salvation Army band struck up America’s national anthem, which they had practiced secretly in pieces. A teenager in the band crumpled to the ground, weeping. American soldiers entered the camp passing out spearmint gum, which the internees chewed then passed from mouth to mouth.

“It was beautiful to watch,” Pearson said. “A clear summer day and the chutes came out like steps in a flight of stairs. Evenly spaced. We burst the gates. Being summer, all I had on were shorts, pass-downs from my brother… no shirt, no shoes, no hat and pretty dirty to boot. I was small and fast and curious. I ran through the gates and headed off to where I saw the chute one of seven had come down. He had landed in a field of cut kaoliang so the stubble was pretty rough even on my calloused bare feet. I came to this soldier who had a buzz cut, had his eyeglasses taped to his temple and was wearing a khaki uniform. When he saw me he had one hand on his sidearm holster and he pointed to his shirt and slowly rotated around. I saw that his shirt had been printed over with Chinese and perhaps Japanese writing. So I said to him, in my very, very British English accent, “Sorry sir, I don’t read Chinese.” At which he relaxed and asked me if the others had landed safely. I told him that he was the only person I had seen. He asked me where the camp was and I started to take him in that direction and then the adults came along and took over.”

“I remember tailing these gorgeous liberators around,” Previte said. “My heart went flip-flop over every one of them. I wanted to touch their skin, to sit on their laps. We begged for souvenirs, begged for their autographs, their insignia, their buttons, pieces of parachute. We cut off chunks of their hair. We begged them to sing the songs of America. They taught us You are my sunshine. Sixty years later, I can sing it still.” Much later in life, Previte spent years tracking each living member of the rescue team down to personally thank them.

Harris remembered babysitting Elliott on liberation day. “She was about two and we were in the same 57 Block, and she had been born in camp. She was very cute and smart and I just loved her and all that liberation day I carried her everywhere including being at the gate to meet our heroes.

“I was so thrilled to meet her at the sixtieth celebrations in Weihsien [2005]. She wondered why I was babysitting while we were being liberated but I know I loved doing it and her mother was probably wondering and worrying what happened to Angela.”

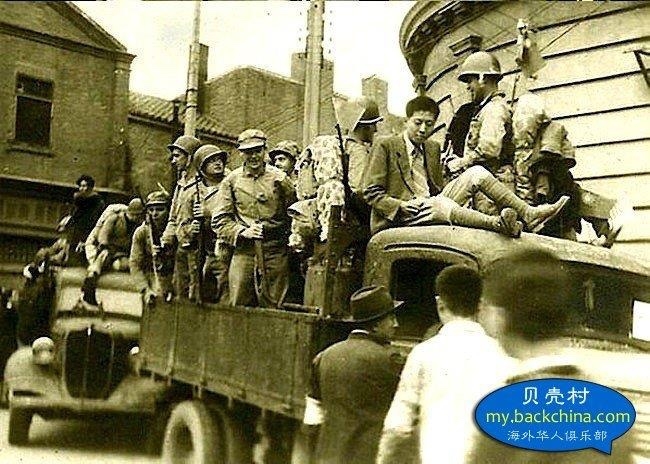

Heavily laden B-29s ruled the skies after liberation, replacing Japanese “Sallys.” Much needed supplies were dropped by parachute into camp, sometimes landing on buildings but injuring no one. Chocolate, hot cocoa, tinned corned beef, raisins, powdered milk, canned peaches, were on the menus while internees waited in some cases months for evacuation. Immediately following Victory Over Japan Day, new perils arose. The civil war between communists and Nationalists renewed with fury, making travel by land unsafe, depending on which side controlled the railroads. No more roll calls were needed, however, and American OSS officers wired the camp with loud speakers, blasting news and songs like Oh, What a Beautiful Morning! and This is the Army, Mrs. Jones.

Some internees found more than their freedom during incarceration. Treadup, according to Hersey, began questioning his own religious upbringing and discovered the busier he became, “the more time he had to do things.” Months before liberation Treadup found a kind of freedom within the strict confines of the Courtyard of the Happy Way.

“Stripped down, all of them, to their most primitive conditions of value… there is a huge hollow place, yet at the same time I am joyous and feel free.

“I am waking up from a sleep.”

Most internees could not return immediately to their homes, due to the ensuing civil war. Some eventually flew for the first time on military airplanes back to Tientsin to find their homes gutted. By 1949, most had been forced out or left willingly, and those that stayed found life increasingly difficult in communist China.

Mary Previte and siblings on September 10, 1945 eating a meal shortly after being flown from Weihsien – “When the plane touched down in Sian [Xian], the men at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) base served us ice cream and cake and showed us a Humphrey Bogart movie . I think it was “Casablanca.” Kathleen and I slept that night in an officer’s tent – unaccompanied by bedbugs. The next night – 9/11 – we were home. We hadn’t seen our parents for 5 1/2 years.” – courtesy of Weihsien-Paintings

Leopold Pander wasn’t two years old when he was “arrested” in Tientsin. His only crime was that he had round eyes, and held a Belgian passport. His memory is naturally vague before his family’s arrest, but he remembers the day of liberation as a recurring nightmare.

“World War II was over,” Leopold said. “I had this nightmare that came back to me, night after night — always the same dream and just before I wake up, I see myself bare footed, almost naked in the middle of a light brown dirty slope, surrounded by big dark grey stones, under a blue sky without clouds and the sun shining bright. People running all over the place. Collective hysteria. I don’t understand what is going on. I am completely panicked. Somebody picks me up — that is when I wake up.”

The recurring dream was a riddle, which took Leopold many years to solve. When he did, he realized it was the hot summer day US paratroopers liberated the camp. For many years after his freedom he didn’t talk about his experiences. “We never spoke about Weihsien, as if it never existed.”

His internment, although he was only a toddler during those years, affected him in a myriad of ways, he said. He prefers silence, never leaves a plate of food unfinished.

“I could stand in the middle of nowhere, stare at a treetop or anything else and not noticing the “time” passing by. My mind would drift away. I could sleep awake. Who can explain that? It still happens to me now.”

The word Weihsien came back to him only fourteen years ago, after retirement. He purchased a computer and learned how the Internet worked and began researching his history. At first he haunted chats pertaining to the Weihsien experience, slowly opening up after finding Father Hanquet, who told him countless stories of the Courtyard of the Happy Way. Not long after he started his own website, www.weihsien-paintings.org, which is a moving collection of memories, pictures and stories of the Weihsien internees.

When Leopold left Weihsien on October 19, 1945 on the back of a lorry, his father told him to have a good last look because he would never see the place again. “Then on the plane back to Tientsin, a C47, quite a bumpy voyage, I was sick. The GIs laughed at me and one nice guy gave me a little stuffed puppy. Gosh. I can’t forget that. My parents left the toy puppy in Tientsin when we left for Shanghai.”

Janette Ley Pander, who is Leopold’s sister, remembers one of her first meals after returning to her family’s empty apartment on the upper floors of the Belgian Bank.

“Being back in Tientsin wasn’t easy at all, we were helped by French friends who had declared themselves ‘Vichyists.’ I had my first real meal at their house: plates, knives, forks, spoons to the right, napkins. Some kind of crinkly green stuff (salad) bathed in oil – uneatable – rabbit meat. What’s a rabbit? I found out and pushed my plate away.”

All of her family’s belongings were gone, and they had no one to blame. “So we, as so many others, started our life all over again.”

Today, the Chinese Government recognizes to some degree what Western citizens gave up during their imprisonment. According to a recent article in the China Daily, a newly constructed 20-meter sculpture commemorates the hardships both foreigners and the Chinese faced during the Japanese occupation at the Courtyard of the Happy Way. “The base is covered by carved Chinese characters that spell the names, ages, professions and nationalities of 2,008 people – 327 of them children – from more than thirty countries,” the article written by He Na and Ju Chuanjiang said.

Although the Japanese government has never acknowledged their crimes during World War II, many former internees found forgiveness is possible and have made return trips back to the prison, parts of which, minus the wall and guard towers, remain to this day. Another reunion of Weihsien survivors is being planned for next year in China, to commemorate the liberation’s 70th anniversary.

“War and hate and violence never open the way to peace,” Previte said in the China Daily article. “Weihsien shaped me. I will carry Weihsien in my heart forever.”

Leopold Pander’s father’s armband – the character “bai” meaning white, or the symbol for Belgium – courtesy Weihsien-Paintings