Native man’s twisted trail into a court system that doesn’t seem to care

By C.S. Hagen

MOORHEAD – With fingers twisted by acute arthritis, Kevin “NeSe” Shores pushed the lever to propel his wheelchair into the Clay County Courthouse. His free hand clutched a large white banker box filled with documents. Folded in worn leather rested an iPhone, his digital eyes.

A driver and assistant followed, told him when to steer right, when to stop. At times, he had to push him through a doorway.

“I’m literally going into court blind,” Shores, an Anishinaabe, enrolled in White Earth Reservation, said. “In the eyes of the court, I’m considered a vulnerable adult, and to cause me any harm is against the law.”

Since the day he received a compulsory cocktail of shots and vaccinations during Navy boot camp, a rheumatoid variant disease he claims is Gulf War illness has broken and bent his body until he can no longer walk and can no longer see. He served aboard the USS Fox, a guided missile cruiser and one of the first ships to arrive during the Gulf War.

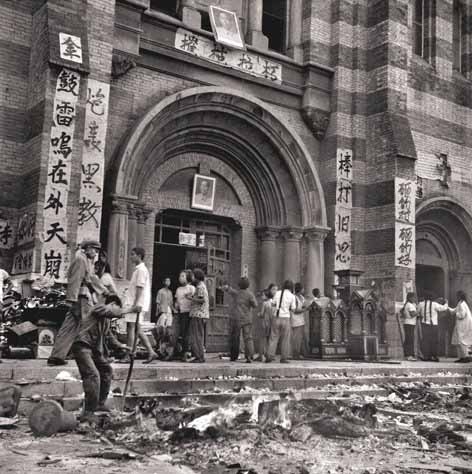

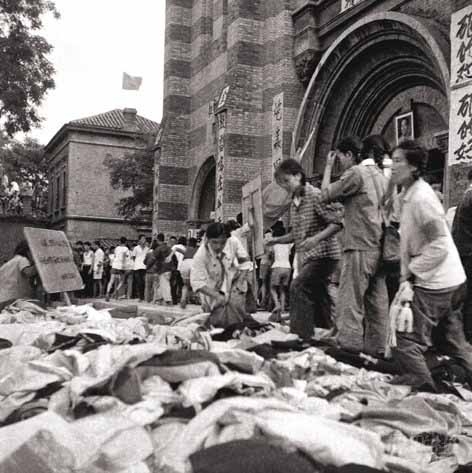

Hands gnarled by an acute arthritic condition, an illness Kevin “NeSe” Shores says is Gulf War Syndrome, he relies on Apps and programs to be able to read – photograph by C.S. Hagen

“As a veteran who is in my wheelchair because I swore to uphold the Constitution, it’s sad that this system that I am allegedly dying for, this slow death, is failing me,” Shores said. “We are in a wrong place as a society. It’s disheartening. I know I’m not the only veteran that is going through this ridiculousness.”

He lost his first marriage due to his symptoms, and a second relationship, a binding ceremony with a Native woman, was recently annulled. Now, he’s defending himself in court for the rights to see his children, and for financial reasons. He says that Clay County Court has failed in notifying him properly, and has ignored his rights under the Americans with Disability Act.

“There is a lot of stress on relationships dealing with this condition,” Shores said. “I’m trying to rectify the situation with the sheriff’s department, and in the meantime I missed a preliminary hearing that I wasn’t aware of.”

Dressed in moccasins, a well-worn black cowboy hat, hair long and cleanly braided, Shores told Seventh Judicial District Judge Steven J. Cahill last week that he was not in court out of his own free will, and because of the court officials’ ineptitude, he missed a court date and lost his parental rights because of it. His computer is six years slow, and he was initially denied using the devices he requires to record.

Kevin “NeSe” Shores and his box of paperwork, none of which he can read due to what he says is Gulf War Syndrome – photograph by C.S. Hagen

“My challenge is I can only go by what I hear,” Shores said. “Since I couldn’t have any of my devices, I had to go back and go through the transcripts, which I had to pay for. I don’t know if you know what it’s like for a blind person to try and search the web. For some reason, I kept missing this one little click spot for the ADA request.”

He can’t afford an attorney, he said, so he prepares everything himself.

“I’m just scrambling just trying to stay afloat.”

During one court visit, he claims a bailiff elbowed him in the face during courtroom drama after he attempted to describe his marriage was a Native binding ceremony, and not a sanctioned marriage.

“How am I to take notes, how am I to prepare for this?” Shores said. “It’s like a domino effect, you have to absolutely stay on top of all of the stuff. Before, I was paying people out of my own pocket for scanning things, but the court is supposed to provide. I am trying to calculate now how much money I spent going back to the original separation.”

All paperwork takes Shores time to scan and listen to.

“As a blind person you cannot serve a blind person papers,” Shores told Judge Cahill in court. This court has trampled on my ADA rights. You have not given me due process of law. My biggest question is why am I here? Why were my children used as leverage when you suspended my rights?”

“Because you were ignoring us, sir,” Cahill said. Cahill was reprimanded in 2006 by the Minnesota Board on Judicial Standards for at least 18 violations of the rules governing the conduct of judges.

“I have not been ignoring you,” Shores said. “I’ve been trying to be compliant.”

After a lengthy tit-for-tat, including Shores asking the judge to recuse himself from the case, Judge Cahill refused the request and ordered the case continued to give Shores more time to prepare. Cahill agreed to order the court to deliver documents to Shores in a manner in which he can scan, but treatments for his illness, and the case, which is against his second “wife,” has left him broke, he said.

“The judge stated that I am more likely going to try to use my disability to get out of court,” Shores said. “And nothing could be further from the truth. The last time I went to court, not only did I get whirly screwed, I had to pay somebody to gather papers, out of my own pocket I had to pay thousands of dollars just to assist me.

“The judge was lying from the get-go that he was well aware of the challenges that I have,” Shores said.

During the years that he did not fall under 100 percent disability, he paid more than $300,000 for care and services, he said. Settlement money for an accident he had in 2000 has been depleted, he said.

Kevin “NeSe” Shores as he exits Clay County Courthouse, is completely blind due to what he says is Gulf War Syndrome – photograph by C.S. Hagen

Gulf War illness

Before Boot Camp, Shores weighed in more than 200 pounds, stood five-feet-eleven-inches, and was the former captain of a local swimming team. The first signs not all was right came shortly after receiving a cocktail of vaccinations. Days later, he was diagnosed with drop foot, a nerve disorder.

“That’s where, I am absolutely sure, I got it,” Shores said.

The military ran the gamut of excuses, Shores said. One explanation was that Middle Eastern sand was too fine for American lungs. They next rational was to blame conditions on mites, then that Saddam Hussein was using biological and chemical weapons, and finally, that they were given experimental inoculations before the war.

A 2008 study by the Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses reports that Gulf War illness is a multisystem condition resulting from service during the 1990-1992 Gulf War, and is the most prominent health issues affecting veterans. The illness affects one fourth of 697,000 U.S. veterans who served. Symptoms include persistent memory and concentration problems, chronic headaches, widespread pain, gastrointestinal problems, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, fibromyalgia, and other abnormalities not explained by well-established diagnoses.

Few veterans have recovered, and until now, there are no effective treatments, the Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses, reported. Two possible causes include the use of pills given to help effects of nerve agents, and the widespread use of pesticides during deployment.

In 1996, Shores accepted his first wheelchair.

In 1998, the same year Congress mandated the Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses to study and advise the federal government, Shores lost sight in his left eye. At the time he was listed as 20 percent disabled, but received little assistance.

Two years later, while riding along Highway 10 at 3.4 miles per hour in his wheelchair from Moorhead to St. Paul to raise awareness about Gulf War illnesses, he was run over by a garbage truck, breaking his femur and elbow and guaranteeing him a hip replacement.

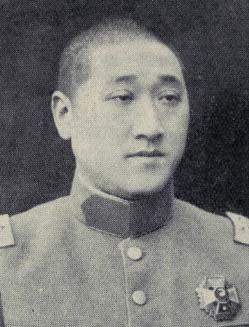

Kevin Shores posing for a picture while aboard the USS Fox in the late 1980s – provided by Kevin Shores

Not until 2005, however, nearly 15 years after Operation Desert Storm, did the Veterans Administration list Shores as 100 percent disabled. Since then, his symptoms have slowly broken his body down. His medications, including addictive synthetic opioids, serve to maintain, not to heal. His spirit , however, remains strong. He has run for the elected position of mayor three times, and has become known as the “megaphone man,” he said. He also does comedy and runs a conspiracy-based Internet radio news show.

“The ‘megaphone man’ because I voice my opinion for the underdogs,” Shores said.

Much like his Indigenous name, “NeSe,” pronounced nay-say, which means someone who speaks truth to power, or is a “maker of great noise, like the thunder,” Shores has never sat still for long, despite his handicaps. He uses an iPhone app as his mobile eyes, and has special scanning equipment at home to help him read.

“I consider myself a traditionalist as much as modern society will allow me,” Shores said. “Your name is your power, you don’t ever share your entire name, except with your mother or father. You only use a syllable of it.”

Because of the secretive and mysterious nature of the Gulf War illness, Shores’ efforts at raising awareness and at conducting research has led him to be labeled as a conspiracy theorist, he said.

“I never really wanted to be a conspiracy theorist, but because of the Gulf War illness, I was thrown into it.”

His online videos are lumped into Bigfoot, aliens, and secret society categories, he said. “Gulf War illness wasn’t talked about, and if you did you were considered crazy. But it’s basically the Agent Orange of 2000.”

The shock from returning to America after three years of service, the inability to find meaningful work, and his slowly deteriorating illness, has left Shores wondering why the country he fought for doesn’t do a little more to help the hundreds of thousands of veterans.

“How do you settle in?” Shores said. “There’s no transition from watching your buddy die one week, to coming to America and listening to a woman complain about choice.”

Shores was supposed to hear back from the Clay County Court’s IT department on Monday, but he didn’t receive a call. He has tried to submit necessary documents online, but keeps receiving errors.

“I have no clue why it wasn’t reading properly, finally I had to ask a person to look over my shoulder and see if I was doing something wrong, and they couldn’t see what I was doing wrong,” Shores said.

“It is absolutely a validation of where we stand in today’s society,” Shores said. “When the entities or individuals that swear an oath and some make the ultimate sacrifice in defending the American way of life in their service to the Armed Forces or other positions of great sacrifice, veterans should not have to continue fighting, not only for their dignity and respect, but for fairness of treatment due to those sacrifices such as disabilities that are a direct result of their service.

“When I joined the military and I said I would die for my country, I didn’t know they would take it literally. For a time I thought I would hate my country for what I am going through, but I love my country. It’s easier to love than to hate, hate just eats you up inside. I just need to survive, to survive, and to go on in this world being the best person I can be.”