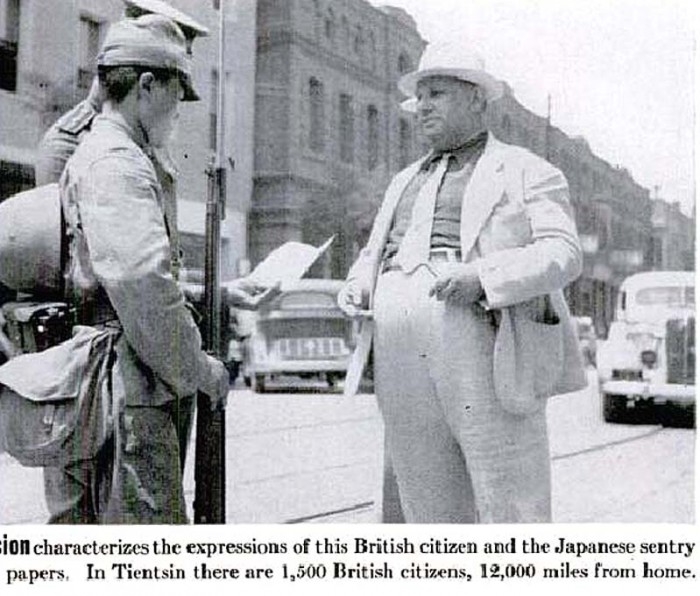

This is the eighth story in the “Tientsin at War” series, taken from the unusual case of a Russian-born British citizen and her bloody struggle through Tientsin’s land of “broken moons,” the world of prostitution. Her story is unique, yet in some respects not atypical of Tientsin’s pre-war streetwalkers and “long threes,” who were an integral and yet unwanted part of the city’s society.

This is the eighth story in the “Tientsin at War” series, taken from the unusual case of a Russian-born British citizen and her bloody struggle through Tientsin’s land of “broken moons,” the world of prostitution. Her story is unique, yet in some respects not atypical of Tientsin’s pre-war streetwalkers and “long threes,” who were an integral and yet unwanted part of the city’s society.

By C.S. Hagen

TIENTSIN, CHINA – Two days after Easter 1930, Katherine Hadley slunk back to her dreary one-room apartment in a wretched section of the old German Concession. Jobless. Nearly stateless. Hopeless. Tears had not dried from her cheeks. Her knockoff purse held the leftovers of her final paycheck – five Mexican dollars. Last night’s vodka claimed the rest.

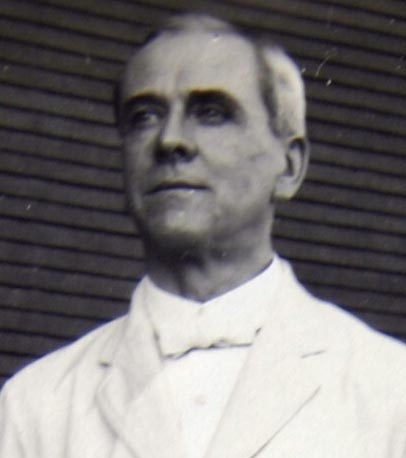

Katherine Hadley – courtesy Daily Sketch

Standing alone at the corner of 72 Woodrow Wilson Road, now South Jiefang Road, her shame returned.

She should turn around. Beg for forgiveness. Promise anything to have them take her back. She’d only sampled the respectable life, but like a pinch of Sichuan peppers the taste burned her tongue. Left her wanting more.

The good life was over, and it was all his fault. Good for nothing ublyudok. Calling her ex-lover a bastard had a calming effect, but made her incredibly thirsty. She needed liquid courage. Alexander Prokoptchik was a gorilla of a man, mean and moody. He surely had a bottle or two lying around, after all, Easter week, a Russian time for celebration, had just started.

Hadley’s real Russian name was Yekaterina Khadlei, but she was commonly known as Tolpige, possibly Tolpyga, meaning “silver carp” in Russian. Tientsin consular and court records cannot claim Hadley had murder on her mind when she found her old room empty of man and drink. Prokoptchik, her ex-lover and mawang, or pimp, was not in.

She checked with her neighbors, asking first if they had seen him. They had not since early morning, and they invited her in for some vodka.

Hadley accepted, taking the first step toward becoming the only woman sentenced to death by English courts in China. Through the efforts of hundreds of admirers and death penalty opponents her sentence, which would not occur until 1934, was commuted to life-imprisonment on the eve of British Minister to China Sir Miles Lampson’s retirement, earning her a one-way trip around the world to London’s Holloway Prison where, according to consular reports, she was to remain for the duration of her natural life.

The Murderess

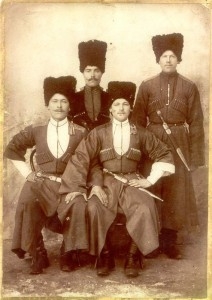

Tientsin and the international press painted a grim picture of Hadley. She spoke Russian and broken English, liked brightly colored dresses and stylish hats. At times, she also wore a smile, cold as a seasoned Cossack’s, and yet wept openly to incur public sympathy when the need arose.

Little is known about her early life, except that she was driven from her motherland by Bolsheviks, and spent an unknown amount of time in Harbin. She procured British citizenship after marrying an English sea captain in 1919, who according to official record, committed suicide shortly after their wedding, when she was twenty-one years old.

According to her own testimony Hadley found easy money in the world’s oldest trade after her husband’s death, working in Tientsin cabarets and houses of ill repute for nearly eleven years. Like many prostitutes of that time, she discovered alcohol helped her nerves, lowered her inhibitions and most importantly, made her forget. Vodka came cheap in Tientsin, less than one US dollar a bottle, and the drink quickly became a curse that would haunt her the rest of her life.

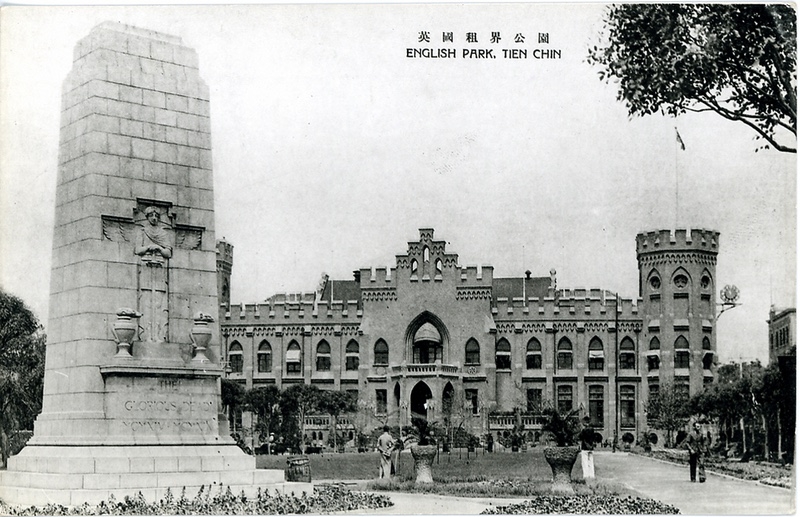

In 1930, however, Hadley’s life took a fleeting upward turn. She landed a respectable position in a well-to-do house working as a nanny for the Watson family’s only child. Usually, Tientsin’s foreigners hired Chinese amahs for the position, but the Watsons preferred a Western woman. She lived comfortably with her employers for a time; meals and salaries were punctual. No need to haggle price or demand pay up front; salaries came at the end of the week. She went on outings to Victoria Park, perhaps even took a summer trip to Peitaiho [Beidaihe], which was one of the favored vacation spots for Tientsin’s foreigners. For the first time in her life, Hadley found respect.

She kept a photograph of the child with her at all times – proof – that she no longer sold her body for a living. Sadly, her dream job didn’t last long. The Watson family was sketchy on the details as to why she was dismissed, but according to Tientsin Consulate records Mister Watson told police he and his wife agreed only that they could not keep her.

Had she made advances on Mister Watson? Did Mister Watson take advantage of her poor state? Did she show up for work drunk? Or was she fired for a simpler reason? Did Mrs. Watson discover her secret past? Or did a jealous paramour leak her real identity to her employers? The reasons why she left the family’s employ are not known, and most likely will never see the light of day.

What is known is that Hadley could never escape her past, nor could she evade Prokoptchik’s seedy intentions, who according to some reports wanted Hadley to live with him, and work for him. He stalked her, pestering her to return to their dismal apartment at 72 Woodrow Wilson Road.

Although Hadley admitted in court she had known Prokoptchik for nearly three years, and had lived with him for nine months, her job as a nanny kept her safe from his intentions. The day after Easter, in 1930, a traditional time for rejoicing, Hadley was fired. She returned to the Woodrow Wilson Road apartment seeking Prokoptchik. When he could not be found she sought solace with a neighbor, Ann Petrovna Urshevitz, known for the sake of convenience in consular reports as Mrs. Karpoff. Ushevitz lived “in sin” with Vasili Karpoff as a couple, but were not married.

She was having trouble with her mistress, Hadley said, and also mentioned a row with Prokoptchik, officially employed as a newsvendor from the day before.

“While accused was sitting and telling us her troubles we offered her a drink of ordinary vodka,” said Ushevitz, according to Tientsin court records. They drank a bottle of vodka and two beers. Hadley paid a dollar for Karpoff to go down to the local yanghang, or foreign goods store, to purchase the drinks.

Halfway through the drinks Hadley flashed the picture of the Watson’s child. She cried, and complained again that Prokoptchik was hounding her. Shortly after, Prokoptchik arrived, heavily drunk. He hid no secrets of his feelings for Hadley.

“’You are mine Katerina’, and he kissed her,” Karpoff reported Prokoptchik said. A knife-sharpener by trade, Karpoff lived in a one-room apartment next to the public toilet. “I offered him a chair but he said he was too tried and was going to have a sleep.”

Urshevitz’s story was the same, but more detailed. “Alexander arrived and kissed her twice and said ‘You are mine,’ then he said ‘I am going home to sleep’ and left the room. His room is next to ours but for the lavatory. When Alexander left the room he did not say anything to the accused but she left immediately after him. Accused was happy and laughing. Deceased was in a bad mood: he was heavily drunk.”

When Prokoptchik staggered out, Hadley followed, intimating the man’s control over her and her intentions. Ushevitz started to clean up the mess left behind, saying in court records all of the alcohol was finished. She left the apartment to carry out the trash and on returning found Hadley standing wearily in Prokoptchik’s doorway. Blood was on her hands and dress.

“She said ‘I have struck Alexander.’ I looked past her and saw him lying on the bed and his shirt was covered with blood and a pool of blood on the floor.”

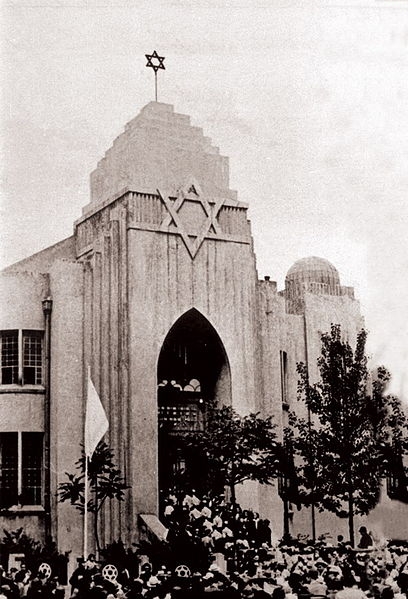

After Mrs. Hadley admitted to striking Alexander, she called for help from a nearby constable named Chang Kuo-pi, of the Special Area Police. He arrested Hadley, and because she had no identification on her, he took her to the Chinese police station. Tientsin provided a shady haven for thousands of stateless White Russian and Jewish immigrants during the 1930s.

Prokoptchik wasn’t dead yet. Hadley stabbed him in the center of his armpit, severing a vital artery with a kitchen knife. A crowd gathered. An American Marine named Robert Hubert Seelos wandered in and attempted to give first aid.

“I took off my cap, belt and coat, rolled up my sleeves and started to try and find the wound: it was under the left armpit,” Seelos, a Marine aboard the U.S.S. Tulsa, said. “The Russian was lying in a pool of blood.”

Seelos cut away the man’s clothes with a second greasy knife.

“I tried to stop the flow of blood by putting a cloth around his chest just below the wound tightly. The blood started to clot and did not flow freely.”

The room, Seelos said, was stuffy and had a foul odor. Bottles and leftover meals were scattered about the room. After doing everything he had been trained to do, a Russian doctor named Peter Michael Sokoloff entered the room. Within two minutes the doctor realized nothing could be done for the wounded man.

“The Marine was pouring water over his [Prokoptchik] chest out of a kettle: I do not know why he was doing this,” Sokoloff said. “I told him to stand aside and tried to find the actual wound under the left armpit right in the middle of the armpit. There was no blood flowing from the wound. It was dry around the wound, which indicated all the blood had come out and the heart was not beating on account of the loss of blood. I noticed two or three faint breaths. I realized that he was dying and no help could be given.”

The Russian, according to Seelos, said three final words, which no one understood. After he died Seelos straightened the man’s legs across the bed and pulled a sheet over his face.

“If the wound had been attended to, that is, if someone had pressed the artery without a doubt this man’s life could have been saved,” Sokoloff said. Alcohol, however, thinned Prokoptchik’s blood and hastened his death.

At the Chinese police station, Hadley became uncontrollable.

Yang Heng-chuan, of the Special Area Police noted in court that he had seen Hadley before, the day of the murder. She was wearing a light yellow dress, and he saw blood on her sleeve and on her right hand.

“She was brought to the station by a policeman: she was drunk and speaking wildly and excitedly,” Yang said. “There was blood and smeared blood, as if she had tried to wipe it off, on her right hand.”

Strangely, Mrs. Watson, Hadley’s former employer, vouched for her British citizenship, saying Hadley was nurse to her child and that, owing to certain troubles, mostly drink, she had left her employment on the previous day, and had not been seen since. Being a British citizen procured certain rights stateless refugees did not have, one of which was to be tried in an English court. She was handed over to the British Municipal Police.

Being without means to solicit a personal attorney, Percy Horace Braund Kent, barrister at law of Kent & Mounsey in Tientsin, agreed to defend Hadley. After pleading not guilty, Kent’s first move was to plead the case down to manslaughter.

Denied.

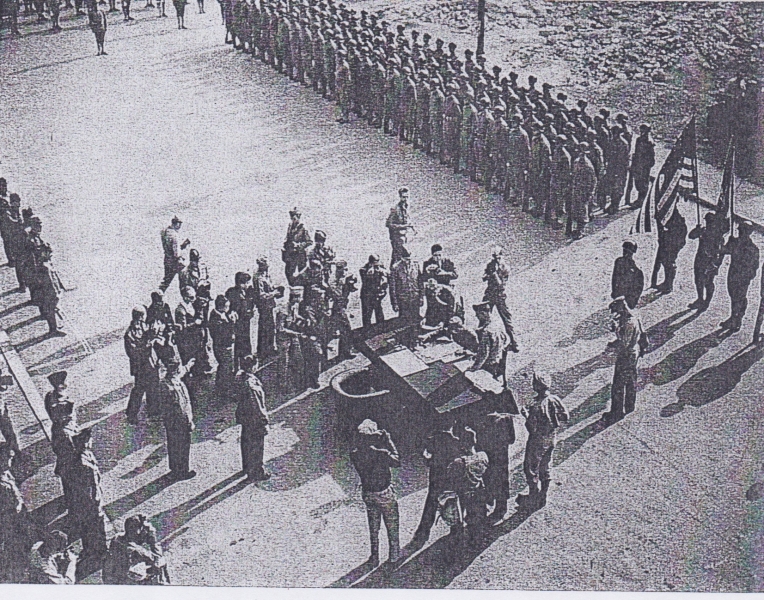

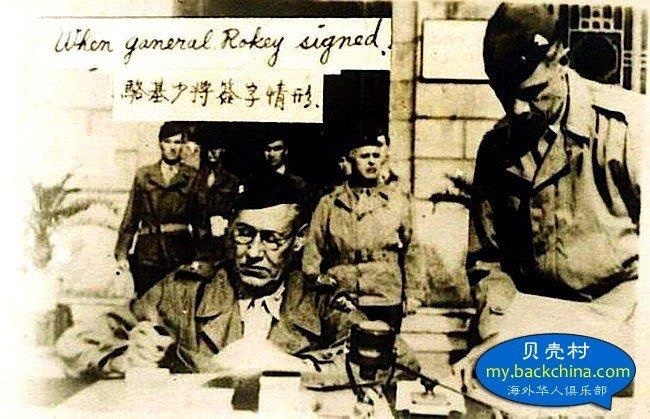

Hadley’s trial for murder began at 10 a.m. on Monday, June 16, 1930.

The wound that killed Prokoptchik was classified as a heavy wound threatening the loss of life but not necessarily under the category of “mortal woundings.” Death was due to a complete loss of blood. The wound was less than five centimeters wide and not less than four centimeters deep.

Witnesses took the stand.

Chief Inspector P.J. Lawless of British Municipal Police took photographs of the murder weapon and checked for fingerprints. The knife, Lawless said, was smudged with blood, but no fingerprints could be retrieved.

John William Hawksley Grice, a medical practitioner, examined blood splatters and determined that the deceased was most likely sitting up in bed when he was stabbed.

G.A. Herbert of the Consulate General’s office found a photograph of a small girl with the glass broken. Broken glass found on the floor fitted into the frame, which was also littered with rubbish, and two knives, one bloody, the other greasy. A third, unstained knife was found in an open basket. Herbert found no reason to believe a struggle had taken place inside the room.

Tientsin’s Consular Court allowed a confession made by Hadley to Michael Joseph Joffe to be entered as evidence against her. “I saw Mrs. Hadley sitting in the police station,” Joffe, a fur merchant, said. “She was heavily drunk. I said ‘You have killed that man, what have you done?” She said ‘I know it and confirm it. I killed him because he wanted to kill me so I took the knife away from him and stabbed him.’”

Prokoptchik was painted as a large man, forty-four years old, standing taller than six feet, with thick shoulders and gangly arms. He was also moody, seemingly tired of life and had sought assistance for delirium tremors. He sold newspapers for a living, but was considered unsavory, rumored to be a pimp, perhaps a small time drug runner as well. No one vouched for his character after his death.

“Why did you kill him?” V. Priestwood, of the Crown Advocate’s Office said.

“We were both drunk, we quarreled and I kill him with a knife quite unknowingly,” Hadley spoke English with a heavy Slavic accent. “I do not know how I did it.”

“What were you quarreling about?”

“I don’t know as I was drunk, and even I did not know how I stabbed him… He said if I was not his lover I would be no one else’s and I repeated that I was going and I was not a child.

“I think he might have done this to frighten me.”

Hadley later mentioned that she had told Prokoptchik she was leaving him, and was going to return to Harbin.

“Mrs. Hadley was in a comfortable position in an English family,” wrote Herbert to consular officials. “Was she not being pressed and pressed by her lover to leave this home and join his filthy hovel? Was she not sick to death of his pestering and so stabbed him in a moment of utter hopelessness as to the position?”

“You must bear in mind, gentlemen, that the charge the Crown brings against this woman in the dock is murder, said Judge A.G.N. Ogden in his summoning up of the case. “They charge her that she did on the 22nd day of April of this year at Tientsin murder a Russian called Alexander… Murder may be defined as ‘When a person of sound memory and discretion unlawfully killeth any reasonable creature in being, and under the King’s peace, with malice aforethought, either express or implied.’”

Ogden further went on to reveal that the people involved in the murder either as witnesses or perpetrators, were hardly better than the society’s dregs.

“I don’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings – you must remember these people are not of the highest education,” Ogden said to the jury. “She cannot remember anything. She never touched the knife. Does not remember being taken by a policeman to the station.”

On June 18, 1930, an impartial jury found Hadley innocent of the murder.

“It may interest you to hear that Mrs. Hadley met Dr. Grice after the trial and told him that she thought she had been very lucky,” Lancelot Giles of the consul-general’s office wrote on June 24th to the Crown Advocate’s office. “Grice’s reply was in the affirmative.”

Two years later Hadley was a suspect in a similar murder in Hankow, although she was never charged. She later moved to Shanghai and into the arms of another lover, and her second official victim. Before moving to Shanghai, Hadley was under treatment for incipient insanity in Tientsin, according to a letter from Consul Allan Archer.

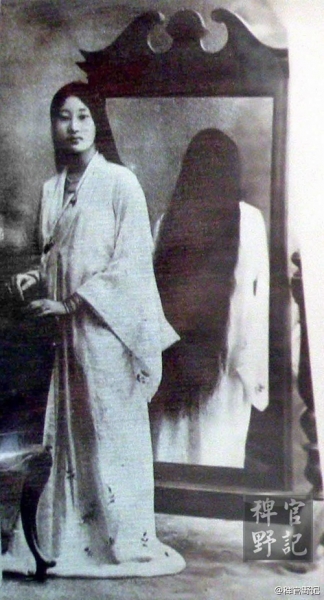

A haunting picture of a Tientsin courtesan, notice upper right hand corner – online sources

Tientsin’s Land of Broken Moons

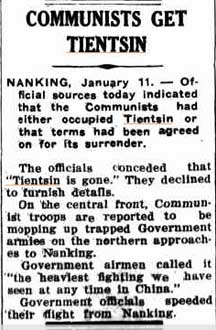

In most Western lands, areas for prostitution are known as red-light districts. The color changes in Amsterdam to blue while in China, yellow is the hue of illicit sex. Prostitution was legal in Tientsin before 1949, and although communists attempted to stamp out the trade and teach former streetwalkers and flophouse girls a trade, turning tricks never truly vanished and is visible, once again, in modern Tientsin.

Their world was known by many names, sometimes called the “bitter sea” or lands of “wind and dust,” or “broken moons.” Working girls who were usually sold or kidnapped and forced into the trade were called “damaged flowers” and when old enough, the road to success lay in competing to the top of local tabloid popularity lists and become a zhuangyuan, or a master of their trade.

Modern day prostitutes are a far cry from the painted courtesans at the turn of the twentieth century. Such courtesans, who weren’t always prostitutes by the strictest definition of the word, were virtually unobtainable.

“Courtesans are the main personages in the brothel,” wrote Gail Hershatter in her book Dangerous Pleasures. “They must be skilled enough to attract guests, gentle and bewitching, and solicitous at entertaining.” Many houses, or brothels, fought over popular courtesans, and they were regarded as “money trees.”

They rode on the shoulders of their boy servants, dressed in the finest silks with bejeweled fingers. To procure a courtesan was nearly impossible for most men, and was considered foolhardy, like “raising golden carp in a jar; they are just good to look at, not to eat.”

Today, such Eastern allure is gone. Classless karaoke girls eager for quick money have replaced the sing-song girls, who once trained their adolescent lives in the entertainment arts, including those of the bedchamber.

Before liberation there were five types of prostitutes in Tientsin. The changsan, or the “long three,” stood at the top of the hierarchy after popular demand for “quick fixes” shrunk the ancient courtesan community. Their nickname was derived from the mahjong domino with two groups of three dots. They charged three Chinese dollars a drink and three more to spend the night, according to Hershatter.

Next came the ersan, meaning “two-threes,” and the yaoer, or “one-twos,” also named after domino patterns. One Chinese dollar included watermelon seeds; two dollars bought drinking companionship. The taiji, or the “stage pheasants” worked in tax-paying brothels known as “salt pork shops,” they sang in sing-song parlors and teahouses, and they charged customers a flat fee of three dollars to spend the night.

Near the bottom of the hierarchy came the yeji, or “wild pheasants.” These girls were tenacious and considered dangerous, charging one Chinese dollar for a “one cannon blast-isms.”

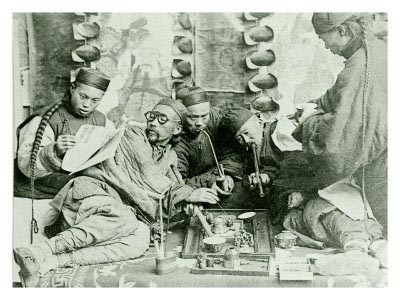

Second to the bottom, not including the aged prostitutes and those working in “flower smoke rooms” or opium dens, were the Chinese girl guides, who charged by the hour and were colloquially known as “sleeping phrase books” or more commonly in recent times as “long-haired dictionaries.” After World War II they became known as Jeep girls, and could be frequently seen riding in US military jeeps en route to a meal at the Astor Hotel.

Although many women were sold into the trade, many also learned to accept they had nowhere else to go. Few initially accepted offers of help. “Why should we eat bean sprouts when in our homes [brothels] servants address us as ‘Miss?’” was one common ideology amongst Tientsin’s broken moon society. When they got noticeably sick, there were painful injections of salvarsan, known by its nickname 606, before penicillin was invented.

Costs of living in China was low, but most of the “respectably” employed could not keep up monetarily with the ever changing times. Labour Cabinet Minister Tom Shaw wrote to consular officials in 1925 that women and children were extensively employed in industrial jobs they were not physically fitted for; their work hours were long, and many had to travel long distances. Foreign and Chinese employers exploited their employees, squeezing thousands into early graves. Entire villages were poisoned through the mining of cinnabar, coal and salt, creating little wonder why many women, sometimes even men, who were known as yazi or “ducks,” chose prostitution to survive.

Most prostitutes had their pimps, known as mawang. White ants, bai mayi, were the traffickers, who usually tricked or kidnapped young girls into the trade, and always sold for a profit.

Customers were known as dry, wet and beloved. Dry customers could spend time and money, but could not afford sexual relations; wet customers bought sexual relations but could not compare to a beloved, which naturally included both sexual and emotional bonds. One of Tientsin’s “baddest girls” included Lin Daiyu, birth name Jin Bao, who became a prostitute at age seven and was known in Tientsin as Xiao Jinling, or “Small Golden Bell.” Although Lin contacted syphilis in Tientsin, she was later cured, hid her pockmarks with thick makeup and became one of China’s most infamous and charismatic courtesans who never stopped seeking a “fatter wallet.”

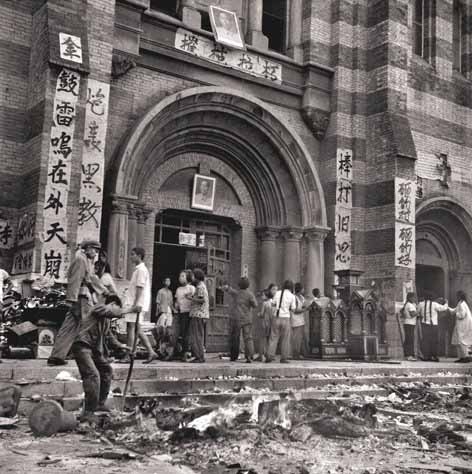

A typical scene inside a high class “salt pork shop” – online sources

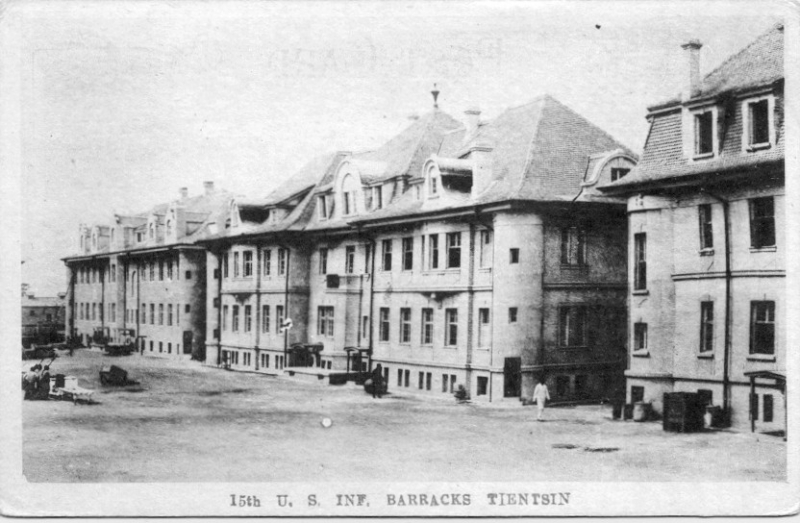

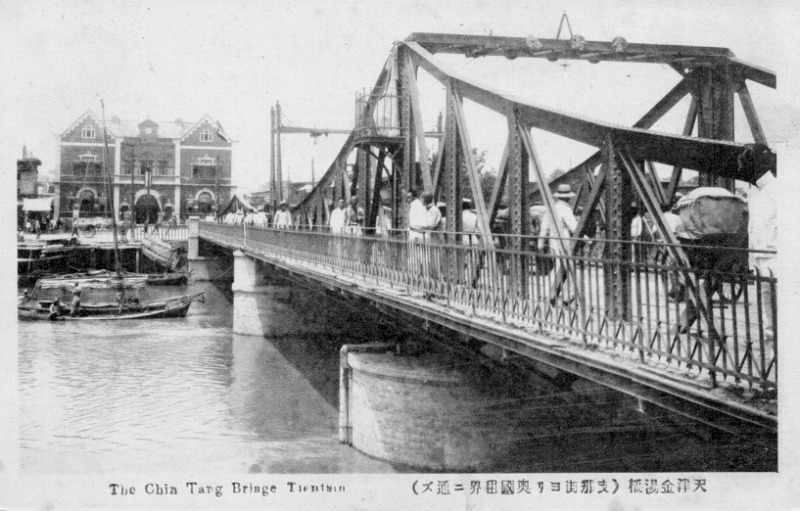

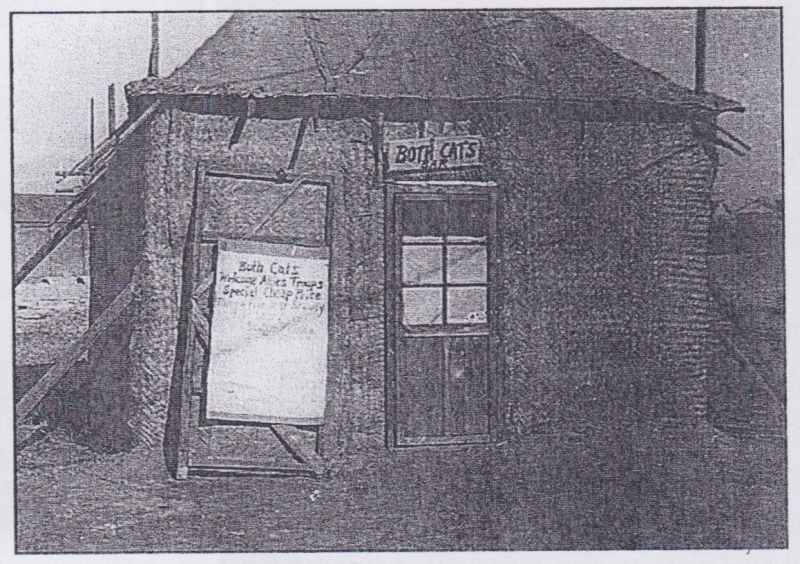

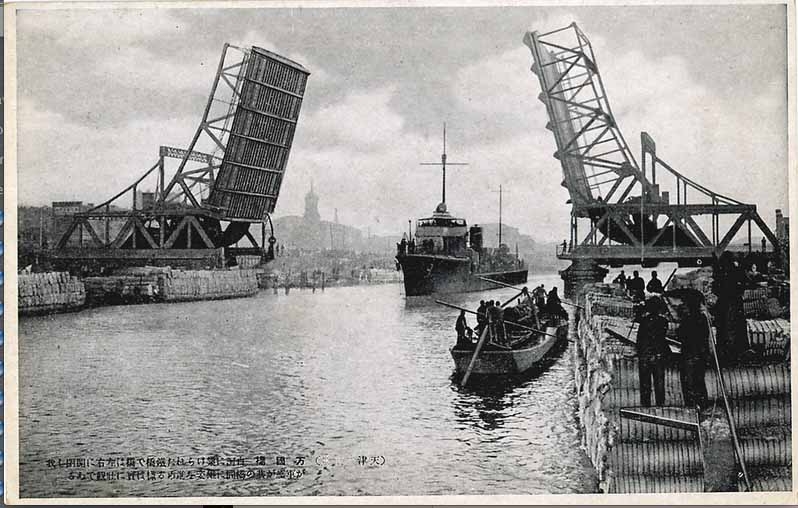

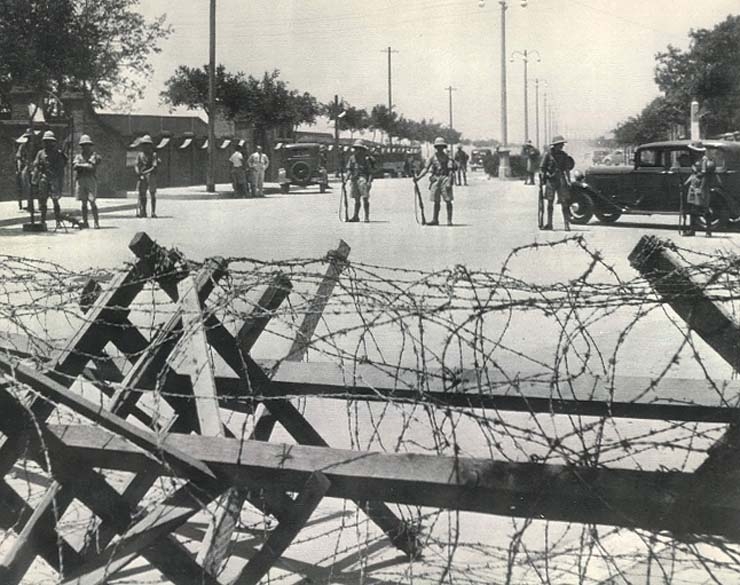

Originally, Tientsin’s brothel areas were outside the north gate of the walled Native City just to the side of one of the city’s largest markets, near present day Food Street shipinjie. Outside the Native City’s West Gate was an area for older prostitutes who served the working class. They were “Charming women of middle age, incarnations of hell, and it is rather hard for them to attract people,” Hershatter wrote. Another area was the Purple Bamboo Grove area, near the old American barracks known as the Muckloo by foreign soldiers. Tientsin’s worst brothels were in qian dezhuang, a sanbuguan at the southwest corner of the city. Here, the better brothels were known as old mother halls, and although they were polite and attentive to mill hands, they lacked the funds for treating diseases.

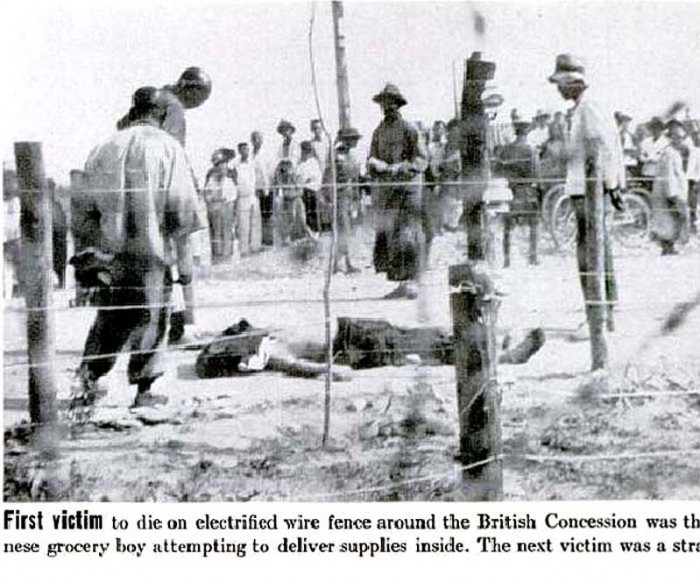

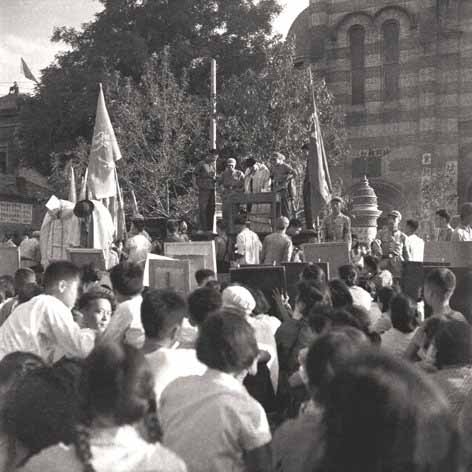

Sanbuguan – 三不管 – A “No Care Zone,” literally translated to mean Three Who Cares and sometimes referred to with a more lengthy description as ‘beyond the control of the three foreign powers,’ (Chinese, Japanese and Western), were boisterous places, filled with cheap theaters, teahouses, brothels, vaudeville halls, devil’s markets, scrap hoarders and dubious drug shops known as yanghangs. The most famous No Care Zone was at the southern edge of the old city of Tianjin, near the Japanese garrison at Haiguansi. Another No Care Zone surrounded Nanshi Food Street, which was infamous for houses of ill repute, opium dens and bandits.

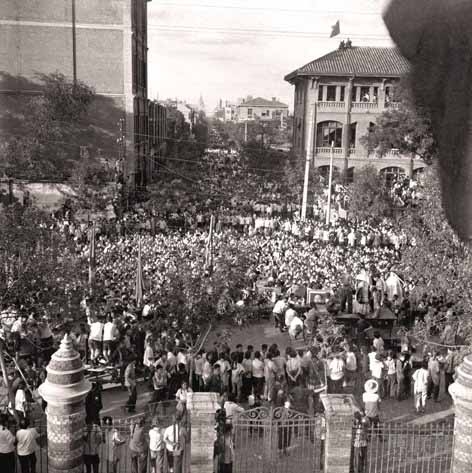

Nanshi No Care Zone – Tianjin Archives Museum

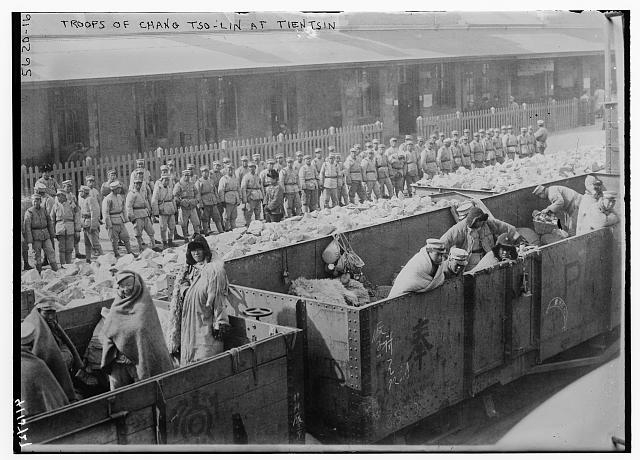

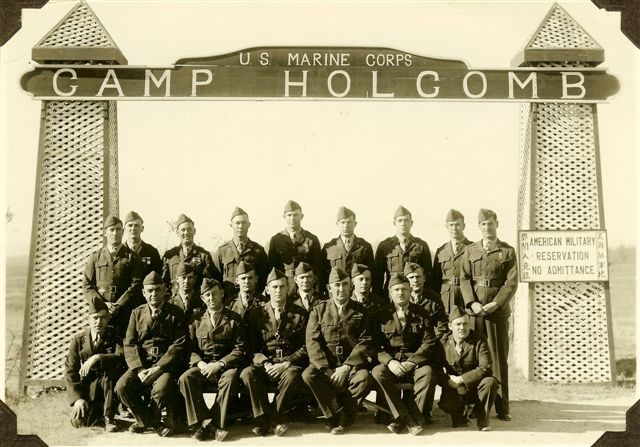

Among the most popular brothels for Tientsin’s soldiers and expatriates were the Muckloo brothels.

“Tientsin was a ready source of women of all nationalities,” reported Alfred Emile Cornebis in his book The United States 15th Infantry Regiment in China, 1912-1938. “A number of brothels… specialized in White Russian women who had escaped the Soviet Union… Many prostitutes lived in the “legendary” street called Muckloo, or Mucklu… not far from the American Compound. Inside the Muckloo were better-known prostitutes such as “Lizzie,” “Peepsight,” and the most famous of Tientsin’s prostitutes “Dutch Annie.”

A modern day teahouse with stage – typical of the old days – where prostitutes would perform dances, sing songs or tell stories all the while being wined and dined by their patrons – photo by C.S. Hagen

Chinese brothels were divided into high-class establishments called “big shops” and the less expensive places, which could be found in the winding hutongs.

The frequent cry still heard today of “lai kele!” or “receive the guest” was the typical welcome heard in any brothel.

Another book written by Hershatter called The Workers of Tianjin, 1900 – 1949, gives a glimpse of business inside a brothel.

“Whenever a guest arrives, a male servant welcomes him, asks him to have a seat, and then lifts up the screen and calls loudly, “receive the guest!” As soon as he sees the fabled beauty enters the room in a leisurely fashion, her hair ornaments moving as she passes by, his eyes are riveted upon her. He may pick a prostitute, and she will open the cigarette box for him and prepare some tea. This is called “having a seat,” and costs half the price of spending the night. If for some reason the guest says that she doesn’t meet his fancy, and leaves, it is called “hitting the chaff lamp” (da kang deng).

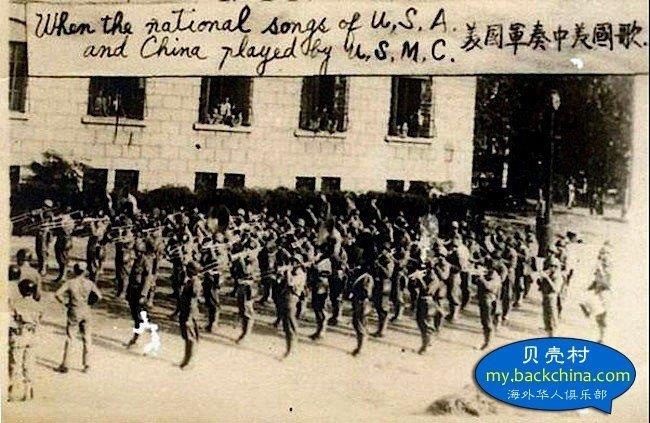

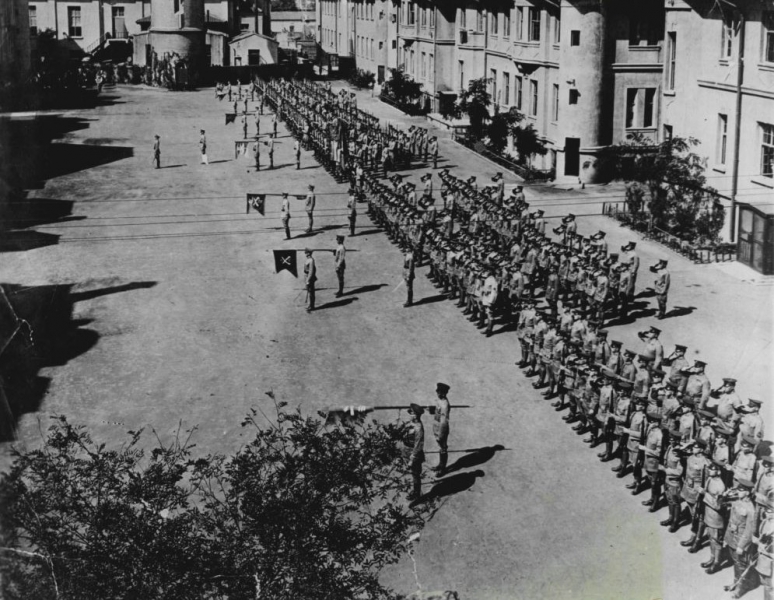

A US Marine in Tientsin – online sources

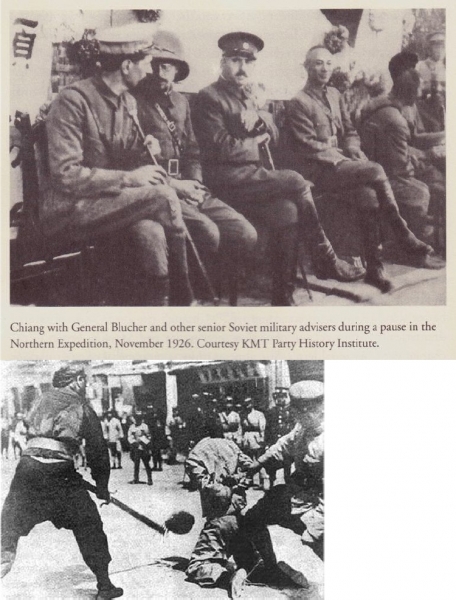

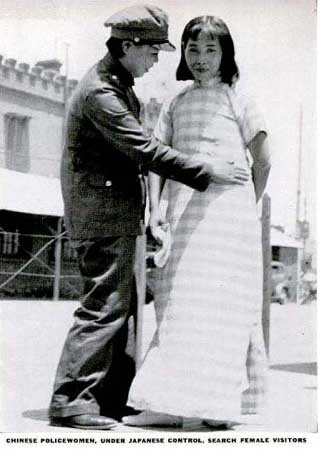

According to 1920s survey by Nationalist Bureau of Social Affairs, Tientsin had 571 brothels, in which 2,910 workers were local Tientsiners. The rest came from Japan, Korea, Guangdong Province, Russia, Poland, United States and other Western countries, and worked mostly out of the Muckloo area, which was also near the British Bund along the Hai River. A perfect escape for US Marines.

“The regiment’s high command was perennially up against two hard faces of Army life in China: their soldiers’ propensity to excessive drinking and their cohabiting with the natives,” Cornebis reported. “There was also concern of drug abuse, and these soldiers were known as “snow birds” but this never became a major problem.”

“Up the pole” referred to being “on the wagon” and mottos like “When intoxication is a bliss ‘tis folly to be sober,” were common. A military sentence for alcohol abuse was one month’s hard labor and two-thirds loss of pay for US Marines.

Colonel Newell of the US Marines frequently told his men to be wary. “You have come to a country where the 18th Amendment is not known and where the temptation to lead a sordid life is in every corner. A man can ruin himself physically in a few weeks.”

Soldiers in Tientsin were recognized to have a venereal disease level at three times the Army’s average, and despite the general ambivalence Chinese prostitutes had toward venereal diseases, soldiers continued to find “sleeping phrase books,” according to Cornebis.

Although the Nationalist Party regulated the trade, prostitutes were categorized into one of the five grades, the largest of which was the third-grade, prostitutes who earned from one to four mao or 40 cents a day, while the fifth grade made from seven fen or cents, known simply as cash, to three mao a day, Hershatter reported from a Tientsin guidebook.

The 18th Amendment is the only amendment to be repealed from the US Constitution. This unpopular amendment banned the sale and drinking of alcohol in the United States, taking effect in 1919, and was a huge failure.

“Third class brothels are more poisonous than those of the first or second class. Lower still are the local prostitutes who live in filthy places. Laborers congregate there. For three mao they are permitted to spend the night… People who come in contact with them immediately contract syphilis, injure their health, and kill themselves… Further, there is a secret kind of secret prostitute who is especially dangerous. Those in this group do not have a fixed address. They come from other places, and use the cover of prostitution to practice their tricks. People who fall into their clutches at minimum will lose their money, and in more serious cases their lives may be in danger. New arrivals in Tianjin, please be kind enough to avoid this pitfall.”

Katherine Hadley fell into this transitory category of streetwalker. With no fixed address, she bounced from one brothel or cabaret to the next, somehow making ends meet. When her first victim, Prokoptchik, tried to pressure her into working for him, she killed him.

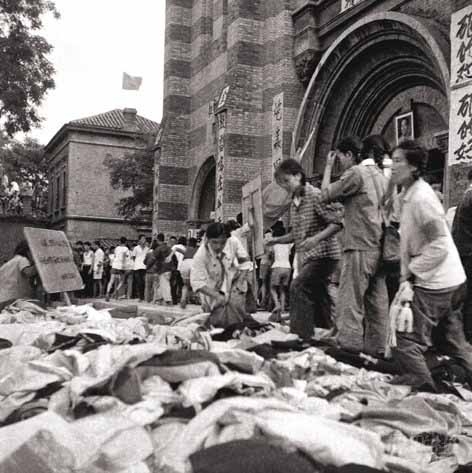

As times progressed, so did attire and Tientsin’s broken moon society. Instead of meeting at teahouses and salt pork shops, more and more prostitutes frequented places such as the French Club or the Blue Fan, which catered more toward foreign customers – online sources

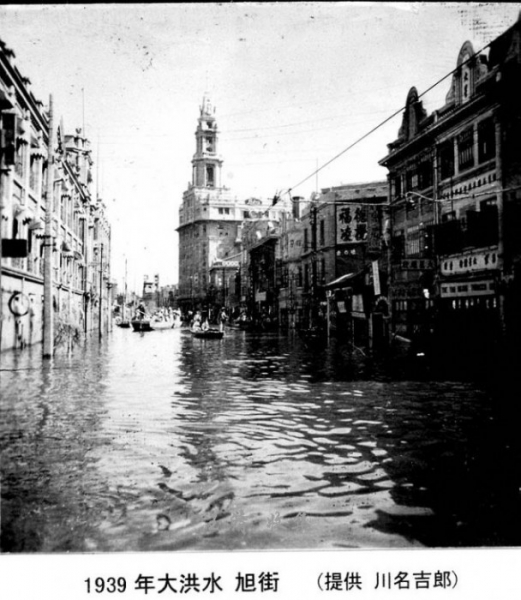

Shanghai 1934

Shanghai’s summers are wet and oppressive, stifling as a ship’s boiler room even when the sun goes down. August is one of the Yangtze basin’s hottest months, a time when there is little escape from tempers spurred by late summer heat.

Efim Rivkin and his wife, Rosa, were trying to cool off on their balcony when they both spied through a window a couple sitting at a dining room table opposite them of Muirhead Road.

“We could see her through the window of the house opposite,” said Mister Rivkin, a barber, in his testimony at the Shanghai Supreme Court. “There were two people in the room – there was a man. They were sitting on chairs. The woman was waving her hand and breaking the crockery. She was holding a knife.”

Rosa said a one-sided argument took place. The man, a Captain Walter Clifford Youngs, sat quietly smoking a cigarette while the woman, Hadley, broke crockery with a knife.

Youngs coolly smoked, but said nothing.

“Then she stabbed him in the upper part of his body,” Rosa said. “He rose a little from the chair and fell down. The woman sat down on another chair and rested her head on her arms. Then after two or three minutes – she got up and went round the table to a chair where a jacket was hanging. She took out something from a pocket of the jacket. It was hanging from the chair on which the man had been sitting. I could not tell what she took out

“When the police arrived she was lying on the bed.”

Michael Koretsky, a neighbor, ran for the police. They soon arrived and Officer Gleb Dubrovsky, who was also an interpreter, entered through the house’s French window and found a man half sitting against the wall. Blood was pouring from the right side of his neck and he covered in blood. “He was still breathing,” Koretsky said. “He was covered in blood.”

While en route to Shanghai’s General Hospital Youngs was still alive. He was quiet, however, while Hadley was talking excitedly and trying to get out.

“In the operating room she was still talking and trying to get up from the table,” Koretsky said. “I was trying to keep her down. She took hold of my arm and said: ‘Did I kill him?’ I did not reply. She then said: ‘If I didn’t kill him, I will kill him ten times over.’ I patted her shoulder and told her to keep quiet.”

Youngs died of a neck wound on August 16, 1933. Hadley was treated for a small cut to her left breast, but doctors never revealed if the wound was self inflicted or was caused by other means.

While in the hospital Hadley asked repeatedly for Eliza Robinson of the Foreign Women’s Home, a shelter for foreign prostitutes and drug addicts. She had called Robinson, known as the Matron, earlier that night.

“It’s Katherine speaking,” the Matron said Katherine told her on the telephone. “Miss Robinson all that you have said has been perfectly true. I made a big mistake in leaving the home.” She said that Captain Youngs had come home much the worse for drink and started to abuse her. He had threatened to tell me what kind of a woman she was. She could not stand it any longer so she left the house. She said she would not come back that night. She would go and see what condition he was in and if things were not all right she would return to the home in the morning. She was not excited – I had no difficulty in hearing her speech.”

But prosecutors in the Shanghai Supreme Court didn’t fall for the Matron’s defense of her one-time ward or Hadley’s heart broken account of her life.

“I was in the kitchen preparing for supper,” Hadley said in court. “And saw the vodka. I was so annoyed that I returned to the kitchen. I brought the food. I sat in front of him. He said I did not know how to cook. I said I would go back to the Cottage. Then he pushed me and called me a bloody whore. I left the house and telephoned Miss Robinson. I went to a Chinese shop and got a bottle of vodka. I drank it.” As she didn’t want to go home, she went to another friend’s house, but saw his wife was standing outside with her friend. “I returned to the Chinese shop and got another bottle of vodka. I don’t remember anything after that until I woke up in Wayside Police Station.”

Both bottles of vodka she did not pay for. “I drank the vodka because I was annoyed – not to get my courage up.”

The Matron later vouched for Hadley’s traumatic life in a letter to Chinese Minister Lampson, pleading to spare her life. “As one who was in close contact with her, and knew her as few did, I wish to testify to her good influence over the other inmates of the Home, where her cheerful submission to discipline and general helpfulness were strongly marked. Katherine Hadley had done her best to secure honest work, but had been pursued by Captain Youngs’ attentions; the sapping of her moral and physical nature by vice and drink, coupled with her defective education and low mentality, wore down her resistance.

When Hadley was at the Foreign Women’s Home, which according to Prostitution and Sexuality in Shanghai: A Social History, 1849-1949 by Christian Henriot, was one of two homes in Shanghai that received foreign prostitutes and also worked with “repentant girls,” Hadley suffered from mental disturbances, headaches, for which she was given bromide three times a day. Toward the end of her stay she had a slight attack of pleurisy, a lung condition, and was bedridden for a week.

“The case is one of a naturally kind and happy woman, of defective education, addicted to drink at periods of mental excitement, carried away by the treatment of a man who had persisted in re-entering her life, till the cumulative effect of excessive remorse, indignation at her treatment, accentuated by the mental excitement already referred to drove her to excessive drink, and then to commit a crime of which she has no recollection whatsoever.”

“I am thirty six [years old],” Katherine said in court. “[I] came to China in 1917. Met Youngs in 1924. He asked me to live with him as his mistress. He said he would marry me. I went with him in 1924. I stayed with him a couple of months.” She went to Hankow in 1925, after Youngs started drinking, and worked in a cabaret. “He wrote asking me to return to him. I asked him to send me money. I borrowed money and came to Shanghai.”

She worked brothels and cabarets in Dalian, known then as Dairen, and at Chefoo and Tientsin, never mentioning the murder charge to court officials.

First page of the petition for Hadley stay of execution, spearheaded by “the Matron” and the British Women’s Association, whose membership consisted of more than 1,000 British women – Shanghai Consulate records

“This year I met Youngs again. I was then in a house of ill fame. He asked me to live with him and I refused. In the house I was drunk night and day. I went to the Foreign Women’s Home and saw Miss Robinson. She took me in – on April 14th I wrote to Youngs and told him where I was. He came one day and asked to take me out. He asked me to live with him and I refused. I said I would much rather stay in the Cottage.”

She called Youngs a “wolf man,” who never failed to hunt her out and force her back to the terrible existence she had begun with him.

And then she said she willingly saw him on Wednesdays and Sundays. “He said he would marry me by American law and make a will in my favour. On July 26th I left the Cottage and we took a room in Newham Terrace.”

According to an October 26, 1933 story in the The Straits Times, Youngs, 54, was a British “gypsy,” and had a reputation of being a reckless soldier of fortune. He arrived in China in 1914, working at Jardine, Matheson and Co., the China Merchants Steam Navigation Co., and for Major Chancey P. Holscomb aboard the steam launch Silver Start, which operated between Shanghai and small islands. He was a gunrunner, a drug smuggler and although he possessed a British passport he had the tough, wiry complexion of a nomad.

After all the witnesses had been called and H.A. Reeks conducted her defense, dependent mainly on the premise she remembered nothing, the jury deliberated for seventy-two minutes before reaching a verdict.

Guilty. But the jury strongly recommended leniency.

Judge Penrhyn Grant Jones then passed the death sentence on October 18, 1933. “Katherine Hadley, the jury has very rightly and properly found you guilty of the terrible case of murder. You have brutally and wantonly taken the life of a fellow creature, and for this the law of England justly claims your own life as forfeit. I find no reason whatsoever why you should not pay the extreme penalty.”

Wearing a bright blue knitted dress, black coat and brown hat, Hadley stoically received the sentence. “Although she received the sentence calmly, she collapsed during the hearing yesterday, and sobbed bitterly as she related the story of a life of misery with a lover whom she characterized as ‘a wolf man,’” The Straits Times reported. “Hitherto no woman has been executed in China by order of a British Court.”

She was sent to the Amoy Road Gaol, one of the British Empire’s worst prisons in the 1930s, to await death by hanging.

The Matron, who was in charge of the Foreign Women’s Home, didn’t give up on her former ward. She rallied friends and opponents of the death penalty to sign petitions, beseeching Lampson for mercy.

Katherine Hadley en route to Holloway Prison. In this photo her knit cap is pulled low over her forehead, and she appears to be fighting back tears while wrenching a pair of gloves. – courtesy of the Daily Sketch and Douglas Clark

“I cannot believe that Katherine Hadley deliberately killed Captain Youngs for although she did not love him she said he had always been good to her and spoke of him in most friendly terms,” the Matron said.

Hadley also changed her tune, saying that her English wasn’t as fluent as she once thought and wanted a retrial. While at the Ward Road Gaol she began showing signs of insanity, reported A.G. Mossop, chairman of the 1934 Visiting Committee for British Prisoners to consular officials. Hadley was sent to the Municipal Council’s Mental Hospital twice, where she improved, but relapsed upon return due to the poor conditions within the Ward Road Jail.

“The Council’s medical officers reported that in their view continued confinement either in the gaol or in the mental hospital at Shanghai was not conducive to the prisoner’s recovery and that sooner or later definite insanity would manifest itself if adequate psychological treatment was not provided,” Mossop wrote.

All 5,607 prisoners in the Ward Road Gaol wore leg irons, W.P. Lambe, an acting chairman for the 1935 Visiting Committee for British Prisoners reported. The warden walked the halls with a baton. Suicide rates within the prison were seven times higher than in other British penal institutions.

Four months after her death sentence and on the eve of his departure from China only hours before the final deadline to commute Hadley’s sentence, Lampson ordered Hadley’s reprieve of execution, according to consular records. “Now therefore I, Miles Wedderburn Lampson, His Majesty’s Minister in China, in virtue of the powers conferred on me by the said Article of the said Order-in-Council, do direct that the sentence of death passed upon the aforesaid Katherine Hadley be commuted to one of imprisonment for life.”

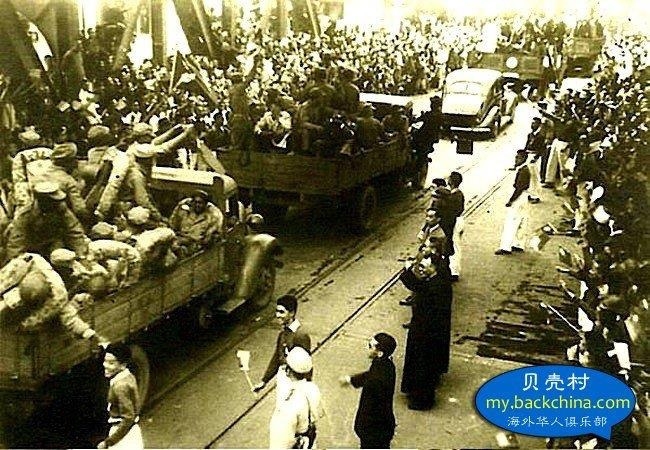

Ten months later on November 8, 1935, and in accordance with the Colonial Prisoners’ Removal Act of 1884, The Times and the Ogden Standard-Examiner reported Hadley was shipped to England, a country to which she belonged but had never seen.

“A journey across the world to serve a life sentence in prison has been the strange experience of Mrs. Katherine Hadley, a Russian-born British citizen,” The Times reported.

She disappeared behind the thick rock walls of London’s Holloway Prison, and was never heard from again.

Gates of Holloway Prison, London

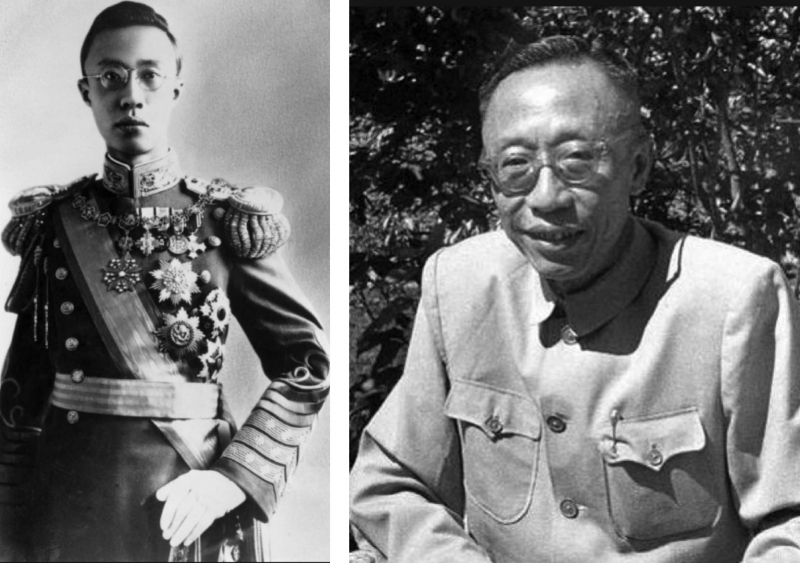

![]() This is the second article in the “Tientsin at War” series, written to remember a mysterious Manchurian spy, presumed dead in 1947. She was officially executed as a traitor to China by the Kuomintang, but recent evidence suggests that she evaded the final bullet and lived until 1978. She was a dreamer, a warrior, a bisexual that charmed her way into the inner workings of her many enemies. Called the Human Devil by the Kuomintang, she was a hailed a heroine by the Japanese. Pour yourself a cup of coffee, sit back, and enter a world of sexual predators, espionage, murder and betrayal.

This is the second article in the “Tientsin at War” series, written to remember a mysterious Manchurian spy, presumed dead in 1947. She was officially executed as a traitor to China by the Kuomintang, but recent evidence suggests that she evaded the final bullet and lived until 1978. She was a dreamer, a warrior, a bisexual that charmed her way into the inner workings of her many enemies. Called the Human Devil by the Kuomintang, she was a hailed a heroine by the Japanese. Pour yourself a cup of coffee, sit back, and enter a world of sexual predators, espionage, murder and betrayal.