By C.S. Hagen

TIENTSIN, CHINA – The sun had set. Mama was braising supper, fresh carp with scallions and cone-shaped corn cakes called sticky bobo, Bangchui’s favorite. Baba, his usual grumpy self, was home from pulling a rickshaw, smelling sweaty, chain-smoking Double Crane cigarettes.

“Bangchui,” Mama said. She gave the giant wok a pull, slopping thickening soy sauce onto the stone oven. Flames burped from the hearth. “Go take a bath. Dinner is almost ready.”

“But…” The twelve-year-old boy’s stomach growled.

“No buts.” Blue smoke hid Baba’s face. “Do as you’re told.”

“Yes, Baba.”

“Should have named you Lazy Worm. You aren’t worthy to carry the Hao family name. Go. Hurry back. The American soldiers always cause havoc on the weekends.”

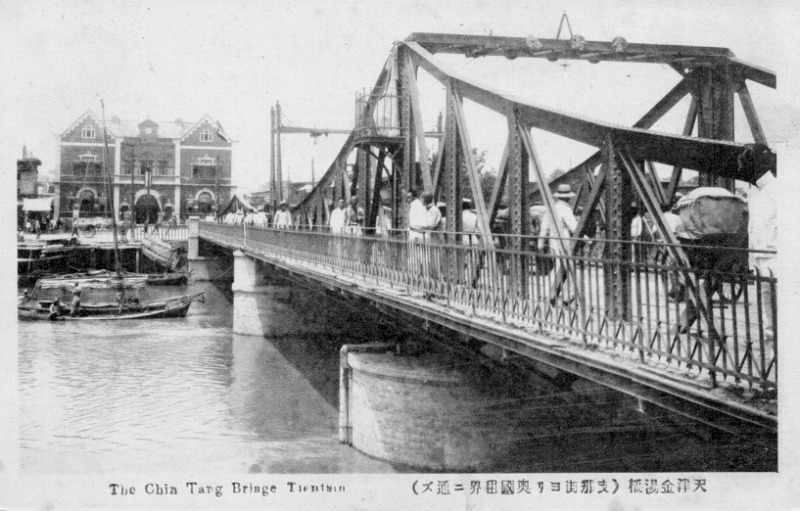

Giving Baba a wide berth, Bangchui closed the rickety front door behind him. The Hai River wasn’t far. He’d spent all afternoon swimming, he didn’t need a bath, and to make matters worse, he was hungry. Despite the lack of streetlights, Bangchui could find his way to the riverbank blindfolded. Perhaps he could catch a water snake or a fat frog to take home and eat, fried with lots of garlic and chives.

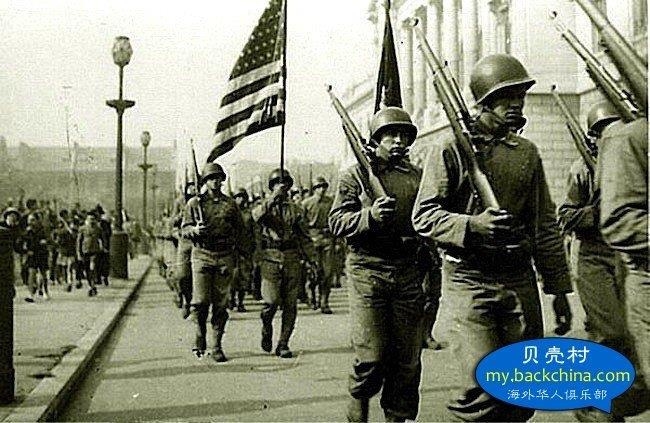

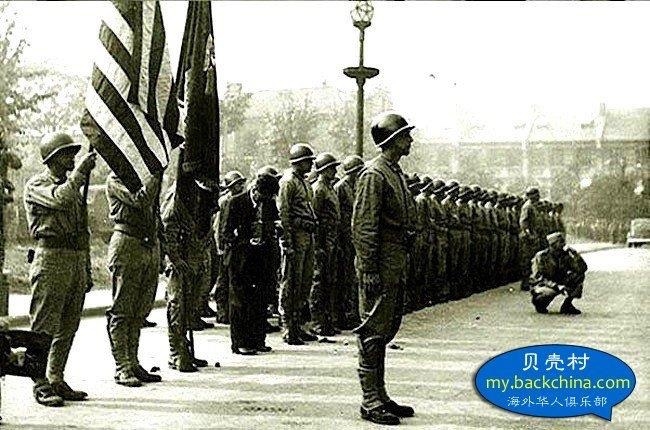

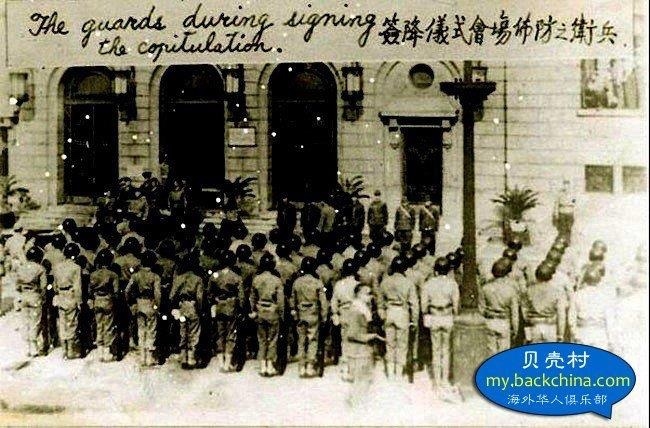

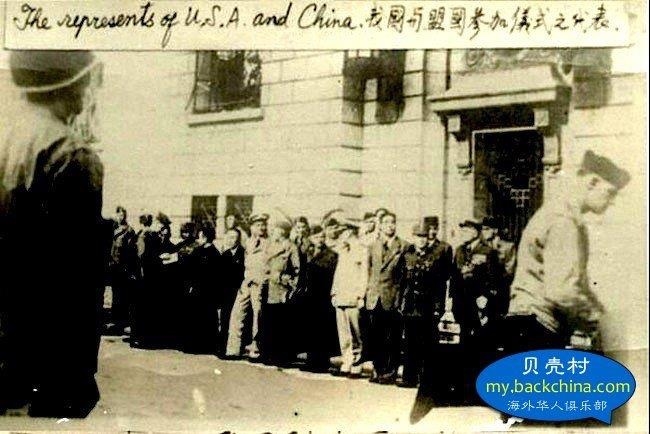

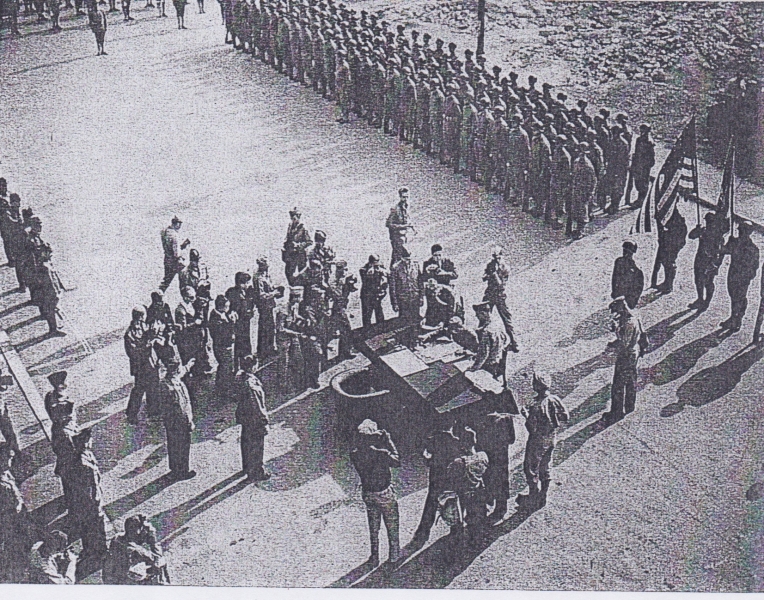

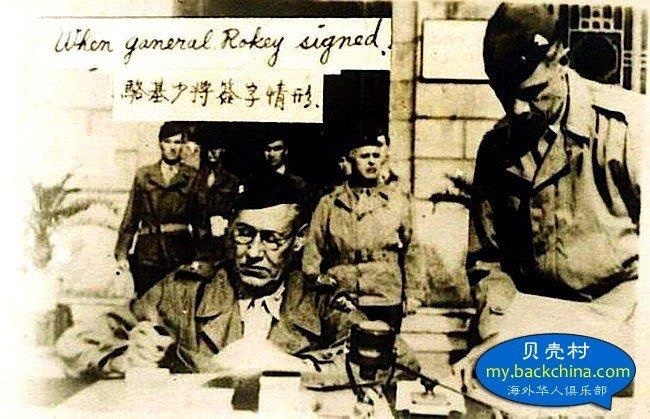

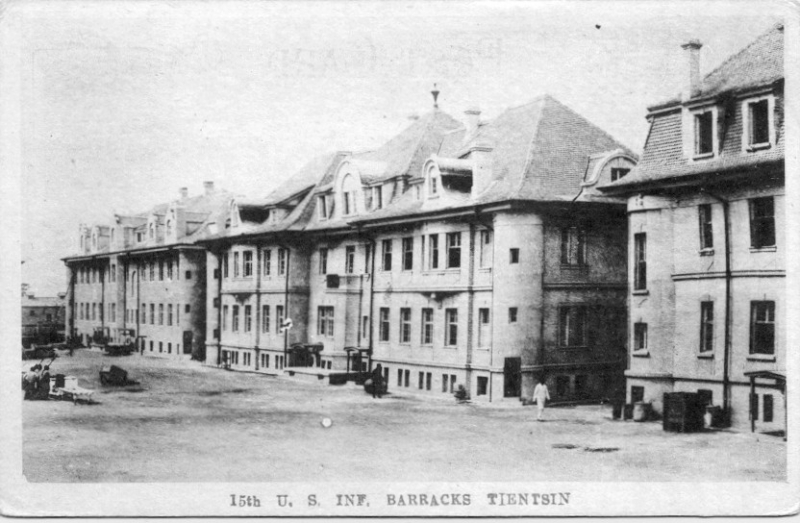

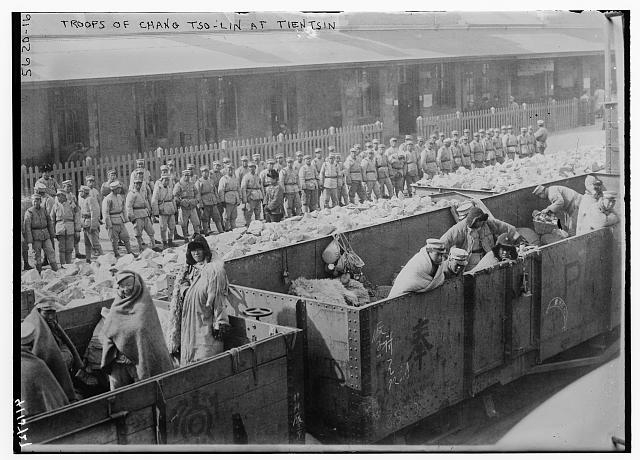

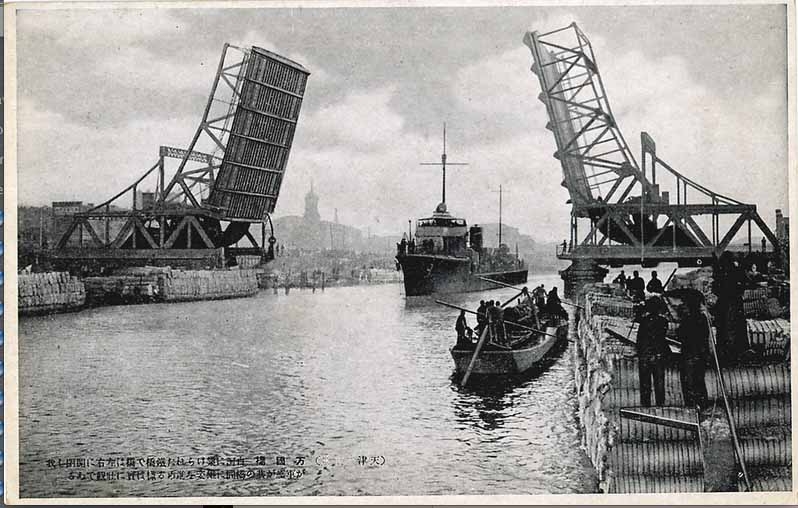

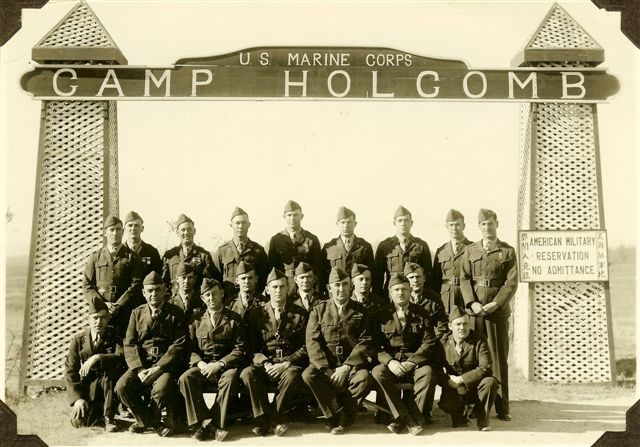

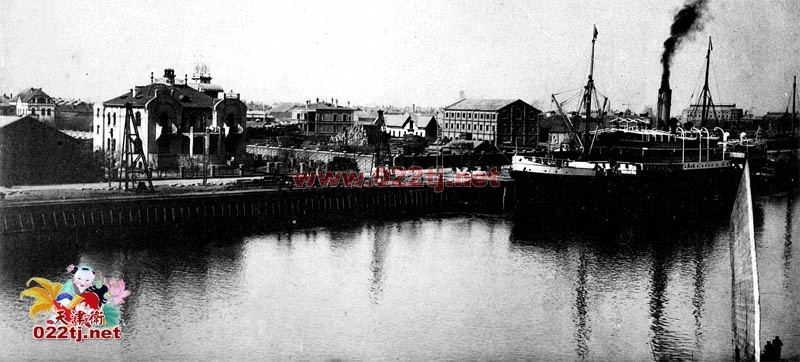

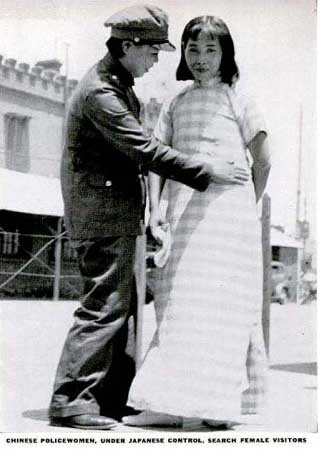

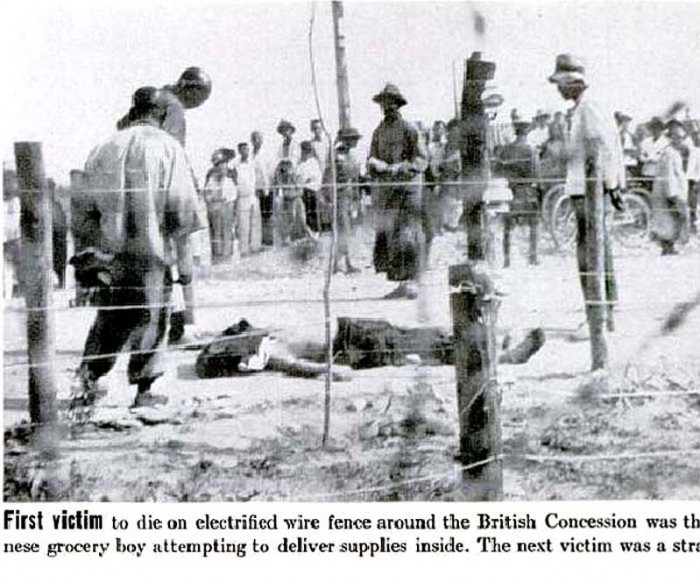

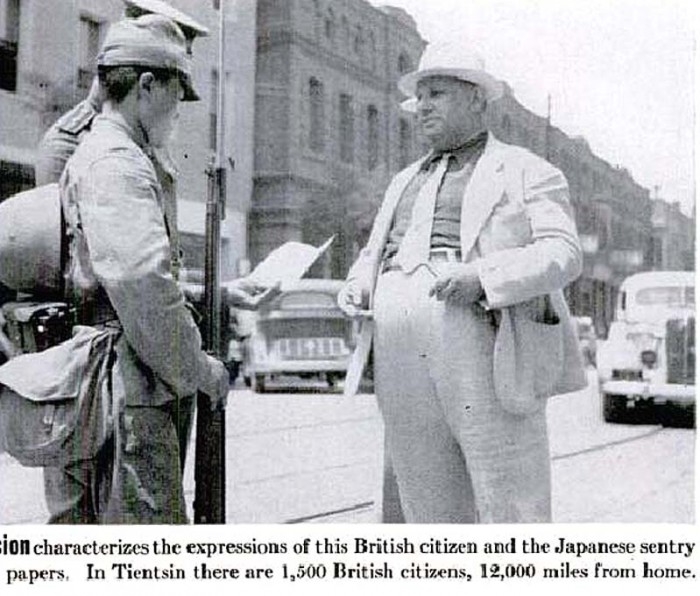

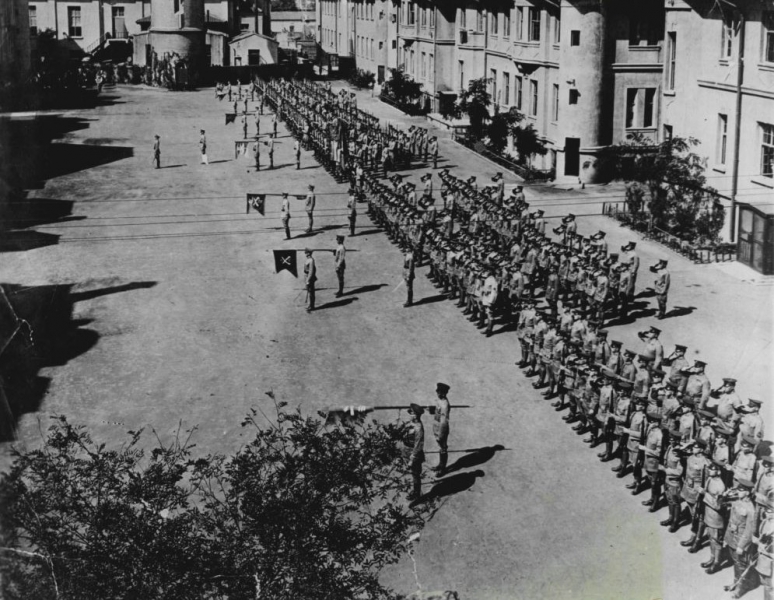

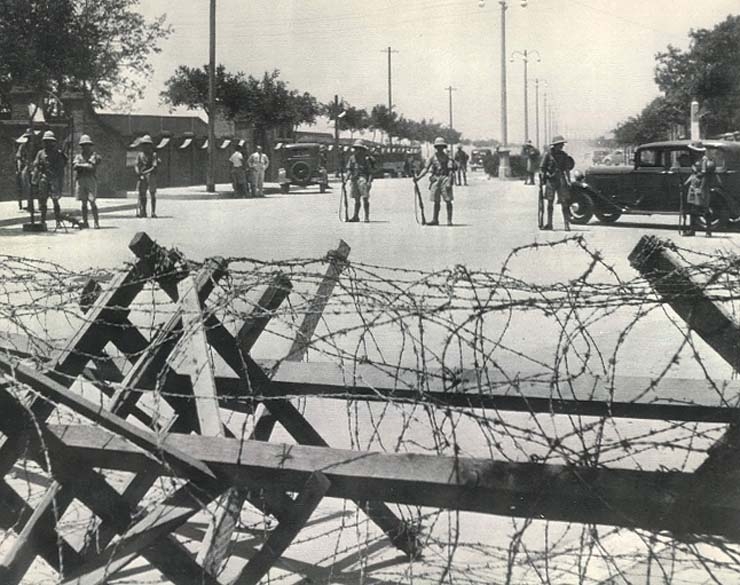

Moonlight painted the Hai River silver, inviting him in. Junks and sampans were silent, bobbing gently. An American gunboat billowed a long smoke trail, heading east toward the ocean. Barely two years since the Japanese surrendered, and the city was swarming once again with foreign soldiers, only these ones resembled monsters from the Monkey King’s Journey to the West. Fiery red hair and burning green eyes, they drove their Jeeps through town with abandon, laughing, and smelling of strange spirits.

Bangchui spat in the ship’s direction. Baba said the Americans were good for Tientsin, but he knew better. Stupid Roundeyes. They couldn’t even speak proper words.

Thick mud oozed between his bare toes. He enjoyed the sensation, and dug deeper, disturbing tadpoles and a frog too small to eat. Not far away, an object bobbed to the surface, winked at him, and then sank.

“What’s this?” Bangchui took a step closer, remembering his clothes. Hurriedly, he stripped and dove naked into the cool waters, his bathtub. Swimming toward where he last saw the object, it resurfaced two meters downstream. He dove, kicking his legs like the mighty Zhang Heng from Water Margin and caught the bundle before it sank too low.

The object was heavy, tied at the top with a string he couldn’t pry apart. He dragged it the river’s edge, and waited for the water to drain. What was inside? Silver? No, silver was too heavy to float. Paper money, yes that was it. Surely some local hooligan had dumped the bundle filled with loot into the river for a quick escape. Or perhaps a communist spy from the Eighth Route Army had lost his cash while fleeing from Kuomintang police. The possibilities were endless.

Making sure no one was watching, he hugged the bundle to his bony chest, and set off toward home. Flat feet smacked the stones loudly, but he was in a hurry. He couldn’t remember one time when Baba had said a kind word to him. Today, his luck had changed. Baba was surely to be impressed.

An elderly couple out for a stroll gave Bangchui pause at the corner to his alley. Squeezing behind a chicken coop, he waited. He could not risk being seen with such a prize. Arms wrapped tightly around the bundle, it felt strangely warm against his bare chest.

Baduum.

It had a heartbeat.

Baduum… baduum… The beats grew louder, faster, pumping into his arms, up to his shoulders and neck. His ears burned. A chicken pecked his bare knee, drawing blood. The old couple shuffled past and then he realized the rhythm came from his own racing heart.

Fingering the bundle, Bangchui suddenly became a huihuir, no, better yet, a Han spy, escaping the Forbidden City with arms full of treasure. He was Li Kui and Guanyu and Liu Bei and Cao Cao, brave heroes from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, all rolled into one. The thought emboldened him. A chicken squawked in protest. He kicked at the cage. The chicken pecked at his toe, missed.

Chuckling, he broke into a run, speeding down the narrow alleyway, and burst into his house. The front door clanged against the earthen wall, showering him with dust from the rafters. Words caught in his throat. All at once the pungent fish aroma, his father’s cigarette smoke, and the oval-eyed, astonished looks from his parents were a breath-taking attack on all his senses. Mission accomplished. Proudly, he hefted the bundle toward the ceiling. “Look what I’ve found.” His voice cracked.

“Bangchui.” Mama nearly shrieked. “Where are your clothes?”

WHEN BANGCHUI RETURNED, clothed, the bundle was resting on the family table. Baba was tugging the string to little avail.

“You’re only making the knot tighter,” Mama said. She brought scissors out from a drawer. “I’m just not sure about these things. Perhaps we shouldn’t open it.” She snipped the first string. “We all know the story about the poor merchant finding a pot of gold along the road.”

A second snip. The bundle loosened, an inch.

“You and your superstitions,” Baba said. “Just cut the strings.”

“The poisonous golden worm, I tell you. Once you let it in the house it might bring you luck, but it comes with a cost, and can only be satisfied with human blood. Best to leave these things where they lay.” She cut the final string.

Baba peeled the bundle’s layers back like a mangosteen’s thick skin. “This is a fine weave.” He fingered the cloth. Bangchui’s heart soared.

Mama’s scream pierced Bangchui’s ears with the nerve-shattering ferocity of a diving Japanese Zero. Suddenly, his skin crawled with Goosebumps. Baba stumbled backward, knocking over a chair, his fingers shaking as he pointed toward the bundle. Bangchui hurried closer for a look. Center table, wrapped in wax cloth, sat a human head.

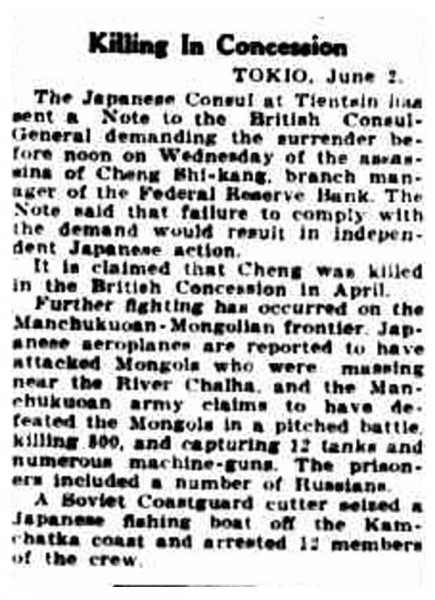

The Case of the Ghost Market Human Head, noted in Tientsin historical documents as one of the “Eight Strange Cases of the Republic,” had begun.

The Restauranteur’s Second Wife

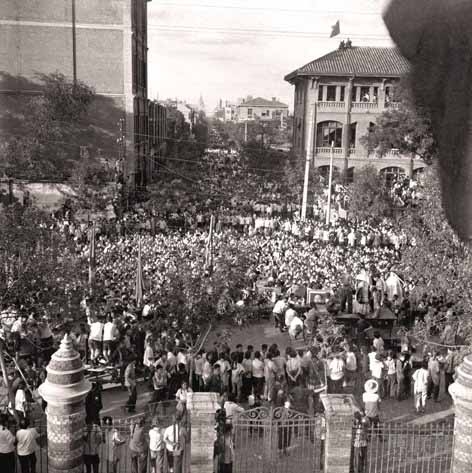

Police Investigator Xia Menghai appraised the crowd surrounding the Hao residence with hesitancy. Another call into the hutongs, third time this week, for his overworked, underpaid, and severely under-appreciated position. Wasn’t easy being a Tientsin police officer anymore. The day before he settled two domestic disputes, broke up an upstart thieving ring, pocketed their scores, and then was ordered into a Nankai University student march protesting the presence of American soldiers in the city.

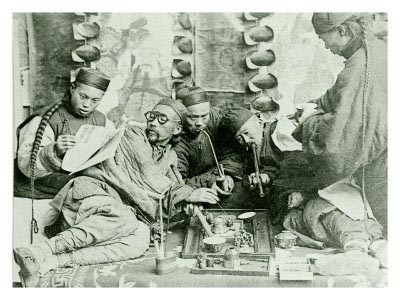

His measly paycheck was hardly enough to feed his wife and two children, not to mention the mistress he kept on the sly lodged in the old French Concession. These days, he couldn’t spend money fast enough to keep up with the inflation. Ends had to be met, however, such was life. He didn’t blink twice when opportunities arose, such as manhandling a plump pimp for petty cash. His favorite, though, was drug smugglers, still shoveling their trade after the Japanese surrender. The call for illegal opium in Tientsin was still as strong, and much more profitable, as it was before the war.

Life was simpler during the war days. Cleaner, somehow. More righteous. If only he was paid enough perhaps he could straighten his ways. Now, he was just another cop, walking his beats, robbing rich and poor to stay one step ahead of his creditors. Investigator Xia sighed. Above it all, however, he was downright bored.

“Inspector, inspector.” A middle-aged man pushed through the crowd and greeted him. Inspector Xia nodded, puffed out his chest, and approached.

“Old Hao, I presume?” Inspector Xia said. “What is all the fuss about?”

“You aren’t going to believe it,” Old Hao said. He was a middle-aged man baring rusty teeth. “Come in, come in, inspector. Please. Have some tea. It’s tasteless as a northwest wind, but it’s wet, and warm.”

“No thank you. State your business. I’m a busy man.”

“Yes, yes, my apologies for bothering a man of your lofty position,” Old Hao said.

Investigator Xia stooped to enter the shack, which reeked of mud and something not unlike sewage. He stifled a cough. Eyes slowly accustomed to the gloom. A one-room apartment. Kitchen. A stone kang doubled as a couch. Hardly room for a family of three. He’d seen it all before, too many times to count. Day-old fish sat uneaten in a wok. Flies swarmed. That was a pity. All Tientsiners, including himself, enjoyed braised fish and sticky corn cakes. Perhaps, these poor people truly did have an emergency after all.

A child, tear tracks across his cheeks, slumped in a far corner. A plain woman, dressed in black pantaloons and a sleeveless shirt, presumably the mother, patted the child’s back none too gently. Old Hao excitedly pointed to a bundle sitting on a small table. The cloth was beyond this family’s means, most likely fine linen.

Without waiting, Inspector Xia peeled back a layer, and jumped.

“What’s the meaning of this?”

“My son…”

“I should have brought backup. Who is responsible? Who is that… that head?”

“Please don’t be angry,” Old Hao said. “I can explain.”

“You better explain, and speak quickly, or you’ll all be wearing shackles.”

“My son was bathing in the river, and he found this head. He brought it home thinking it was treasure. Oh why, couldn’t he have left it alone? No good son of mine. He’s too curious for his own good.”

“Is this true?” Inspector Xia turned his wrath on the son. “What is your name?”

“Bangchui.” The boy wiped snot across his nose.

“Bangchui? What kind of a name is that? Why are you called a wooden hammer?”

Old Hao stepped too close. Inspector Xia held out a hand.

“We named him Bangchui so that he would be passed over by the King of Hell,” Old Hao said.

Inspector Xia had heard of such beliefs. Not prone to superstitions, he gave little credence to the seven hells or any heaven. Some lesser folk, however, believed in bestowing strange names to their children in order for Yan Wangye, the King of Hell, to overlook them.

“Do you have witnesses?” Inspector Xia said.

Bangchui shook his head.

“He’s a good boy,” the boy’s mama said. “Ask the neighbors. He thought he was bringing home a prize.”

Inspector Xia grunted. He’d seen beheadings before, during the Japanese occupation, and while he was fighting the Island Dwarfs in nearby Shantung Province, but not in Tientsin. The boy had sticks for arms. He doubted such a poor family had anything to do with murder. More than likely expected a reward, though.

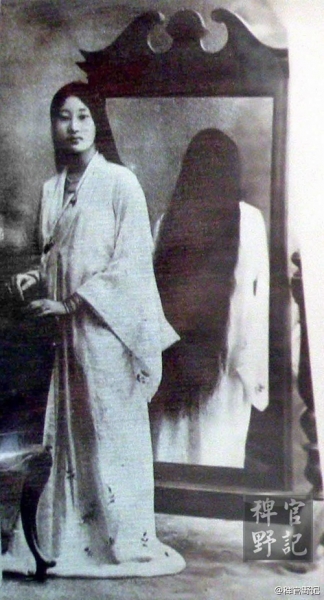

“So who is this woman?” He peeled back a layer, eyeing the head. Young, even pretty, for a severed head. Long, black hair, lips thick as mandarin orange slices.

“We don’t know,” Old Hao said.

“Very well. All of you need to accompany me to the police station.” Mama gasped. “I’m not charging any of you. Yet.” Inspector Xia hefted the head. Heavier than he thought possible. “First, Bangchui, show me where you found it.”

A TRAFFIC POLICE officer identified the severed head. It belonged to Liu Shi, second wife or the er nainai of Wang Jinyuan, the famous Suxiang Zhai restaurant owner. Inspector Xia smelled a family quarrel, but when he arrived at the Wang residence, the house was quiet, tidy. Old Xu, the Wang household manager and his personal wine-meat friend, was finishing up an argument with a watermelon seller, saying the melons weren’t ripe, and had to be taken away.

Old Xu invited him in for tea.

“What can I do to help you, Inspector Xia?” Old Xu smoothed his long shirt across his legs, adjusted wire-rimmed glasses. He was a decent looking man, neither too thin, nor too fat, middle aged, without a wrinkle, and teeth white as ivory. He was a wine-meat friend because they were not close, but had met when the occasion called at Suxiang Zhai for drinks and dinners. He didn’t appear ill at ease with the inspector’s sudden arrival, but then a man of his position hadn’t achieved such success by wearing his emotions on his sleeve. Old Xu signaled for a servant to pour tea.

“How is Wang Jinyuan’s health?” Inspector Xia asked of Wang Jinyuan. The tea was fragrant, perfectly warmed. The servant left the teapot’s spout pointing directly at Old Xu, a mistake, in the olden days, worthy of dismissal.

Old Xu nudged the teapot’s spot toward the wall. “Well enough,” he said. “Does your arrival have something to do with Wang Laoye?”

“Umm, how is his first wife?”

“She is well. Thank you for your consideration. Why do you ask?”

“How about Wang Laoye’s grandmother on his father’s side?”

“She passed away years ago. Really, old friend, what is the reason for all these questions?”

Inspector Xia paused for emphasis. “And how about er nainai, the second wife?”

“She is well, although I haven’t seen her for several days.”

“You haven’t seen her?” Inspector Xia pushed back his chair and stood. “And why is that exactly?”

Old Xu nearly dropped his teacup. “They live in the interior of the compound. I stay here with Zhou Liang and Pang Guang, the runners.” Old Xu pointed out the Ming Dynasty window to where two young men sat idle in the courtyard. “Perhaps she isn’t feeling well.”

The answer made sense, but Inspector Xia wasn’t entirely convinced. Everyone was guilty in his mind until proven innocent. Still, he wasn’t going to get any easy information if he leaned on the suspects too hard without ample reason.

“I have no authority over where or when she goes.” Old Xu said. “Would you like to speak with Wang Laoye?”

The invitation stole some wind from Inspector Xia’s sails. It wasn’t proper for him, a simple police investigator, to barge in on a man of Wang Laoye’s position without evidence. “That wouldn’t be proper. I think it’s best you bring him the news.”

“News?”

Inspector Xia slumped back into the chair. A powerfully sour feeling rose from his gut, stinging his throat, warning him this case wasn’t going to be easy to solve. His teacup was empty. “News, old friend, of the direst kind.”

A Terrible Fright

After Wang Laoye heard the news, he was overcome with grief. And not the faked kind, Old Xu noticed. His boss was genuinely distressed. Old Xu tried to placate, insisting there was no need for him to personally identify the head, but Wang Laoye wouldn’t hear of anything else.

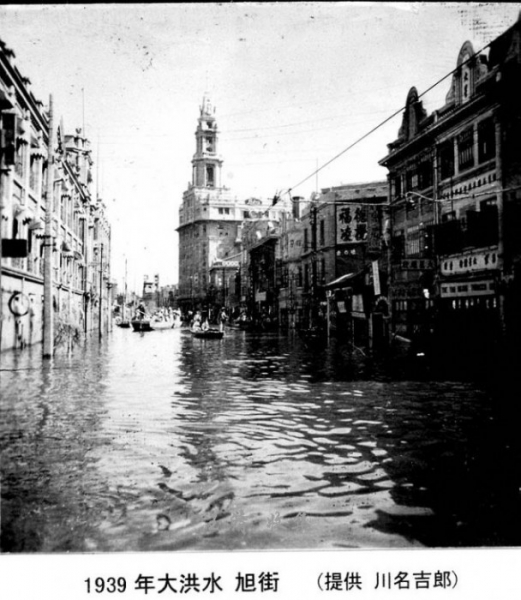

News of the murder swept through Tientsin faster than a Gobi Desert sandstorm, scooping all local news agencies, including the Takung Pao, the largest newspaper company in the area. Poor neighbors gathered around the Wang family’s large estate, nestled into the old city’s north side, begging for an audience. Some wanted to sell their living daughters to replace Liu Shi, the second wife. One woman, approximately Liu Shi’s age – around twenty-two – offered to commit suicide on the spot for a small fee, to be given to her children, so second wife could be buried with a body.

Noble though the requests may be, Old Xu denied them all. Second wife’s head was stored in an old wooden ice chest. Despite police efforts to find her body, two days passed, and then three. The funeral could not wait. Preparations were made, and second wife’s head was buried in a full-sized coffin with ceremony in the Wang family cemetery.

A new commotion stirred in Tientsin one week after the burial. Liu Shi’s body was discovered in a watermelon patch outside the city. The watermelon farmer, Lao Jia, was arrested, and later released for lack of evidence. Inside the Wang family’s mansion, preparations, once again, were made to reunite second wife’s head and her body, but the ordeal called for someone with surgeon-like hands, to sew the pieces together. Lao Xu turned to the local Da Liao, who was actually a teahouse owner, wise man, pharmacist, and brave soul, capable of such a chore.

“In those days the Da Liao was a type of local wise man,” the radio report from FSM Telecommunications Corporation on Dot FM reported. “People turned to the Da Liao anytime they were in trouble, and the Da Liao was expected to have the answers.”

Because second wife’s husband, Wang Laoye, was a pillar in the community, the Da Liao agreed to the gruesome deed. A second funeral procession, including Wang Laoye, Lao Xu, the Wang family runners Zhou Liang and Pang Guang, who were to dig up the grave, attended. Wang Laoye, in his distress, carried the white soul banner, a responsibility usually reserved for a son or daughter, and led the small procession to his second wife’s grave, weeping the entire route.

Second wife’s severed head and body could not be touched by sunlight, moonlight, and starlight; a golden blanket was spread across the grave. Blindly, Da Liao pried open the coffin, inserted a hand, and went no further.

“What is it, Da Liao?” Wang Laoye said.

“Don’t be afraid,” Da Liao said.

“Is her head there?” Wang Laoye pushed his formidable weight forward, short moustache twitching in anticipation. “What are you touching?”

The Wang family runners quailed, and dropped to the ground.

“I am touching a hand,” Da Liao said.

“What?” Wang Loaye pawed at the grave’s side, kicking up dirt like a dog digging a hole.

“Stop.” Da Liao said.

Wang Laoye slumped to his side. The white soul banner lay on the dirt beside him.

Da Liao closed his eyes and reached further inside the coffin. “I have found the hand again, and there is a body. Are you sure you only buried a head?”

“Yes.” Wang Laoye wailed. “How can this be? Has my beloved wife grown a new body?”

“Don’t be silly.” Da Liao withdrew his hand to throw back the blanket.

“No.” Wang Laoye shrieked. “We must wait for morning. I am a Scorpio, anyone who dares move will have to deal with my sting.” Old Xu was confused to what Scorpio meant, and feared his boss was losing his mind. Wang Laoye struggled to his feet, picked up the white soul banner, and began parading around the grave, chanting like a priest.

The Da Liao relented to Wang Laoye’s wishes, sending Lao Xu to bring Tientsin police. The group waited until morning, and in the presence of a grumbling, sleepy-eyed Investigator Xia, threw back the golden cover, revealing a man’s body in Daoist robes meticulously placed beneath second wife’s head. The man had half a purplish birthmark on his neck, and no other injuries besides a missing head.

The sour smell sent onlookers recoiling in disgust. Zhou Liang and Pang Guang fled home.

Ghost Market Delights

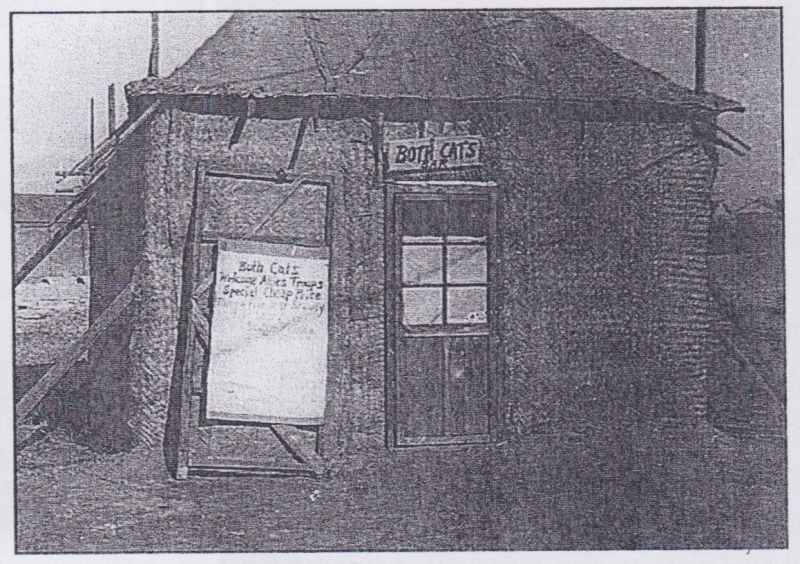

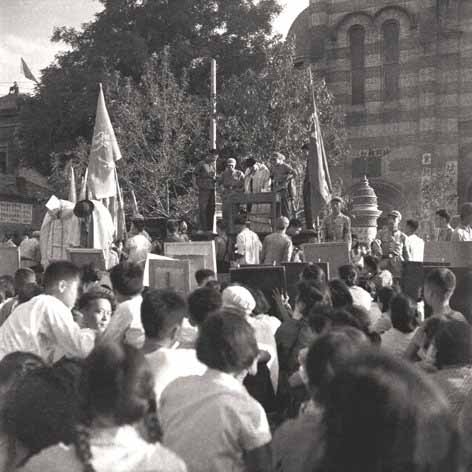

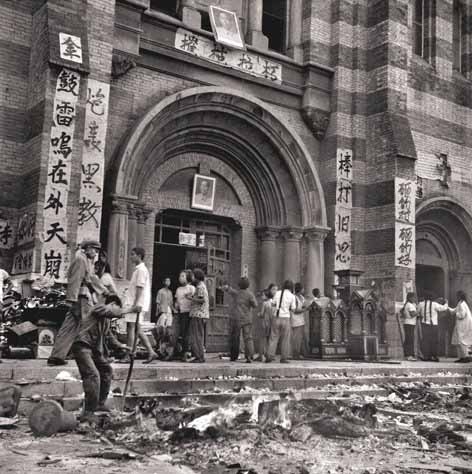

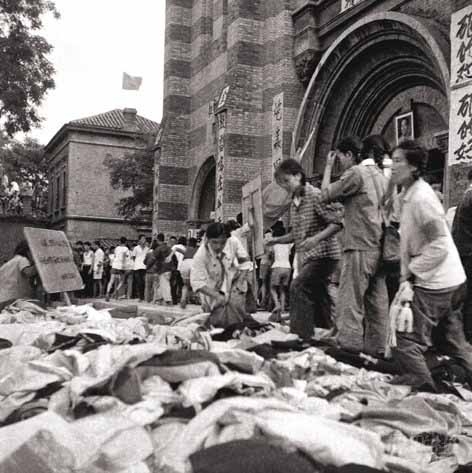

Ghost markets are not named for hauntings or the sudden appearance of apparitions. The name stems from a Chinese idiom, “cold enough to crack a ghost’s teeth,” for they appear silently before the dawn, at the coldest time of day, and vanish with hardly a trace. Merchants lighting pipes and hand-rolled cigarettes from a distance resemble ghost lights, better known as will-o-the-wisps.

Another reason for the chilling name is that a ghost market’s vendors spread their wares on a rug, using the darkness to disguise chipped teacups, torn sweaters, and stolen goods. Their hearts have demons, according to local vernacular, meaning the merchants have ulterior motives, covering up scratch marks on a bicycle with charcoal, or deftly stuffing the wool back into a pair of ripped winter pants. Ghost markets are also places for the poor to sell their meager possessions, and for the less fortunate or curious wanderer to find a trinket or two, the replacement piece for a dish set. Always barter. Never accept a price at face value. Examine the goods closely, and if possible, simply stay home. Thieves, pickpockets, and sometimes murderers, are a ghost market’s specters.

LATE SUMMER, 1947, He Laofu found his usually corner at the Xishi Avenue ghost market in Tientsin’s Nankai District. He spread out his rug. Placed bottles, glass cups, and trinkets in the middle and a stone at each corner. He arrived early, settled into the damp chill by lighting a hand-rolled cigarette. Down the street other early birds arrived, but here, they left each other to themselves. Nobody wanted to know another merchant’s trade.

A faint object not far away attracted He Laofu’s attention. He quietly stepped over and found a bundle wrapped in fine cloth, round, and heavy as a watermelon.

“Who left this here?” He Laofu spoke to himself. “A thief?” The thought dawned on him in the thick darkness. If a thief left such a wonderfully wrapped bundle in the middle of a desolate ghost market area, surely, a prize was inside. He could not open it here. Onlookers would grow envious. He stowed it in his corner, wrapped in a shoddy blanket.

Business was better than usual, and before dawn, he set his prize in the center of his rug, pulled the corners into a second bundle, threw the entire package over his shoulder to go home. He told a neighboring merchant he was sleepy, and that business was too poor to continue. The merchant agreed with a heavy sigh.

He Laofu surprised his wife making the morning fire. “Why are you home so early? Did you make it rich?” His wife said.

“How did you know?” He Laofu placed the mysterious bundle on the table. His wife’s eyes lit up like fireflies in the darkness of their tiny home. “You may have the honors.”

He Laofu’s wife opened the bundle carefully, trying to save the strings. “Oh, finally, our luck has changed. How we must have angered the gods to have led such a poor life so far.”

He Laofu leaned closer, smelling a faintly metallic stench. He wished his wife would hurry, but he kept his lips shut. She had the barbed tongue and quick temper of a Tientsin woman, and he didn’t want a provocation today.

Suddenly, wife screamed. Bile rose in He Laofu’s throat, and he threw himself against the wall. A man’s head, one eye gummed shut, the other opened wide, stared a dagger through his heart.

“Impossible.” He Laofu shouted, and then he fainted.

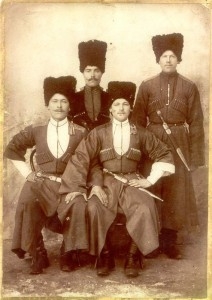

A Huihuir’s Life is the Life to Lead

By 1947, Tientsin’s huihuir, or Dark Drifter societies, pronounced hunhuner, were watered down to a faint shadow of what they had been during the Qing Dynasty. They no longer sported the long queues and flowered wigs. Nor did they carry ax handles and walk the streets dragging one leg. Occasionally, a huihuir wannabe was inspired, perhaps by a father’s stories, to walk into a small shop, slice a meaty thigh chunk away, slap it on the counter and demand free food, but without the numbers the huihuir society once had, individual hooligans had little sway.

Wars, revolutions, and bearing the brunt of too many crimes their members did not commit, dwindled the huihuir down to a laughably petty few.

Broad-shouldered Wang Siwen and his teenaged gang, however, longed for the old days, where huihuir were powerful and a young boy’s name could strike terror into a merchant’s heart.

Wang Siwen called himself Really Big Shrimp. His second in command chose the moniker Bad Luck for Life. Their top general was Hero, more a perpetually-nose-picking-ogre than teenage child. Typically, huihuir came from Tientsin’s poorest areas, including the No Care Zones, and the South Market, or the Nanshi Food Street, but not so for Wang Siwen and his gang. They hailed from wealthy families in Huangjia Park, near the old Concessional area. Wang Siwen and his gang enjoyed reading books, fishing, and other more civilized hobbies. They were known to perform good deeds instead of fighting and causing messes like their predecessors.

“We aren’t creating a name for ourselves,” Bad Luck for Life said. The huihuir gang was lounging in a park. Wang Siwen looked up from the classic Water Margin, cleared his throat.

“What do you mean?”

“We’re always doing good deeds. We haven’t gotten into a fight, well… ever. How are our names supposed to be feared far and wide if we don’t go out and cause a mess?”

Wang Siwen closed his book. “Do you all feel this way?”

Bad Luck for Life, Hero, and the others nodded. Dissension among the ranks was not good, and the boy had made a valid point. By anyone’s account, Wang Siwen’s gang resembled the Red Cross more than bloody huihuirs.

“Very well,” Wang Siwen said. “I propose a quest.”

The boys shifted excitedly. Hero stopped picking his nose.

“A quest for gold and treasure beyond your wildest imaginings,” Wang Siwen said. “All of you, go, now, and don’t return to me until you’ve procured some treasure. Steal anything you can.” Wang Siwen leaned back up against the gazebo’s pillar, reopening his book.

“Aren’t you going too?” Hero said.

“Did Liu Bei, the great king of Shu in the Warring States Period actually go out and fight?”

“Umm…”

“The answer is no. He didn’t. At least not very often, and only when he absolutely had to. My job is here, watching the fort and planning our next move. Now go, leave me be.”

Wang Siwei spent the hours reading until he grew bored, and then played hopping chicken with some neighbor children. At dusk, he returned home, ate his fill of dumplings, and waited under the family’s mulberry tree for his gang to return. Baba rarely ventured outside. The gnarled tree was as secretive a place as any. One by one Wang Siwei’s boys returned, each spreading out their finds as if in tribute to a king. Wang Siwei grunted at a ball of string, some flatbread, a handful of salt, and an orange cat. He cursed when Bad Luck for Life revealed an empty American whiskey bottle, but grew interested when Hero lugged in an oversized bundle.

“I stole this from a dog,” Hero said. The bundle made a squishy noise when he set it down. The general was beaming.

“Well. What is it? Open it up.”

Hero spent an eternity pulling the strings every which way, until it finally came loose.

“Aiya.” Wang Siwei sucked in a sharp breath through his teeth. Hero fell onto his ample bottom. Bad Luck for Life’s whiskey bottle shattered on stone.

In the midst of Wang Siwei’s huihuir gang, grinning through bloodied teeth, sat the bloodied head of a young man, long hair tied into a loose topknot. A purplish birthmark stained his neck and cheek.

“What’s all that racket out there?” Mama called from the house.

“Nothing, Mama.” Wang Siwei said quickly. “We’ll clean it up.”

The youngest huihuir began whimpering. “Hush,” Wang Siwei said. “Crying isn’t going to help anything. Quick, Hero. Cover it up.”

“I’m not touching it.”

“You will if you want to stay a huihuir.”

Hero reluctantly covered the head with the cloth. Wang Siwei strode between his little gangsters, stroking his beardless chin. Suddenly, he had an idea.

“What luck, Hero. You’ve done it.”

“Huh?”

“We’ve a proper quest now. Our job, brave blood brothers, is to find the killer. We will be inscribed as heroes into the annals of this fair city. We will find rank, power, and riches beyond our wildest dreams. No longer will we have to kowtow to…”

“Siwei.” Mama called again from back door. “It’s time for bed.”

“Just a minute, mama.”

“Now, child, or there’ll be no snack.”

Three Heads, Two Bodies, and No Motive

Inspector Xia finished his third fried bread stick and half of his rice congee when a deputy thrust his office door open. Before he could speak, five children entered carrying another bundle.

Congee lost its appeal. He pushed it to the side.

“Another head?” Inspector Xia said.

“What?” A tall, broad shouldered boy bowed. “Wait. How did you know?”

“Bring it here. I suppose you had nothing to do with the murder, correct?”

“Correct, elder brother.”

Inspector paused. Elder Brother was a term used in gangs and the old huihuir societies. These boys wore fine Zhongshan shirts, their teeth were clean, and hair washed to a shine.

“You simply stumbled onto the head?”

“Correct, again, elder brother.”

“I took it from a dog.” A stout teenager with a finger in his nose said.

“Did you now? And just where did this take place?”

“Near the river, not far from Xishi Avenue.”

“The ghost market, yes. As I thought. Very well.”

Wang Siwei set the bundle on his desk, and then introduced his gang with exaggerated pomp, swearing he would do anything needed to find the killer.

Inspector Xia puzzled over the teenagers’ nicknames, but he’d seen too much strangeness since the case began to ask the names’ significance. The room flooded with curious police officers, and he flipped the bundle open.

The room filled with a pregnant silence.

“Hello, Mister Chu,” a young police officer said.

“You know this man?” Inspector Xia said.

“Surname is Chu. Forgot his name. He’s a frequent caller at my favorite brothel. Another Luzu Temple monk.”

“Are you sure?”

The young officer pointed. “Sure as that birthmark is shaped like a spoon. Hope that helps.”

“Yes… well, I’m not sure. Yet. I need to think. Go find out where he lived.”

The police officers filed out, taking the head. Wang Siwei and his gang remained. All smiles.

“Listen, I may need your help after all. Do you think you can locate two runners from the Wang family residence?”

“The Wangs that own the shoe store on Victoria Road?” Wang Siwei said.

“No. The owners of the Suxiang Zhai restaurant. You know of it? Good. I am looking for two boys, Zhou Liang and Pang Guang.”

“Are they the murderers?” Wang Siwei said.

“I just want to speak to them.”

The nose-picking boy withdrew a finger. “I know Pang Guang.” Hero said. “We went to school together. He lives in Hong Qiao District. He’s getting married soon.”

“Very good to know. Go and keep an eye on his house. Report back to me anything you see or hear.”

“Yes, sir.” Wang Siwei said in English, saluting with his left hand.

The boys left, leaving Inspector Xia staring at his half-finished congee. So far, second wife had been reunited with her body. Mister Chu was identified and put back together. The remaining head belonged to a Daoist monk surnamed Shan. Lao Xu had helped him identify the monk, who had frequented the Wang family house on many occasions. What was the connection? Who was the killer? Was it one person, or were there more? He had interviewed Lao Xu, and the big boss himself, more than once. Second wife, Liu Shi, had frequently left with Shan to visit Luzu Temple where Shan lived with another monk named Ren Likui. The two had been roommates. Had second wife broken her marriage vows with Shan? Nothing seemed amiss during the interview, but Ren Likui admitted his friend had been missing for nearly a week.

Other police officers had been searching for the Wang family runners since the day after their disappearance. What was he missing? Police investigation entry level taught relatives, or friends commit most murders, had to be someone close to the deceased. His blood began to boil. Never, in his policing days, had he ever felt driven to solve a case. Usually, the shackles were placed upon the first, and easiest, suspect he could find. Never mattered until now.

Inspector Xia slammed a palm on his desk. Congee spilled. He needed to have another talk with Ren Likui. The first visit had been brief, and the Daoist too calm, too poised. His answers short, albeit courteous. Almost as if he was ready for him.

Ren Likui

The Daoist monk opened the door to his shack at Number 7 Xinyili. His former pearly complexion had darkened. Once perfectly combed hair was ragged. Dark bags sagged under his eyes. Inspector Xia didn’t miss the momentary surprise on the monk’s sage like face.

“Sorry to disturb you,” Inspector Xia said. He was tired of running in circles, and decided on a more direct, disturbing approach. Bending the rules was his specialty, and if it didn’t work, no one would be the wiser.

“You look tired.”

“I haven’t been sleeping well.”

“Guilty conscience?”

“Would you care for some tea? It’s from the Yellow Mountains. Good for …”

“No. Thank you. I’ll come straight to the point. I hear you and Liu Shi, you remember her? Wang Jinyuan’s second wife? Good. Anyway, I hear the two of you were lovers.”

Ren Likui quailed. “Lovers? Where did you hear such a lie?”

“A bird told me. Is it true?”

“No. No. No. I’m afraid that’s not quite possible.”

“Don’t lie to me anymore.”

“I’m not lying.”

“I think you are.”

“If you must know, I prefer a different type of company.”

“What do you mean?”

“I prefer the company of a warm-hearted soul, and not a snake, like Liu Shi.”

“Meaning?”

“I like men, Inspector Xia. That is no crime.”

“It’s not.” Inspector Xia surveyed the tiny room Ren Likui and Shan had shared. One large bed, crooked, and a simple washbasin. Books, scrolls, writing brushes were scattered across a table. Two chairs. Winter robes hung from a wall. No kitchen. They must take their meals in the temple. The ground was laid with bricks.

“We found Shan’s head this morning.”

Ren Likui stifled a sob.

“You loved him?”

“With all my heart.” Ren Likui sat on his bed. An opposing bed leg rose off the ground.

Inspector Xia kneeled, peering under the bed. Bricks bulged upward, strange for an old dwelling. Typically, after decades of use, the bricks compacted, or sunk. He had never seen bricks rise.

“Appears you have a floor problem.”

“Yes, yes. You see how I live. Wu liang tian zun.” A Daoist mantra for praising the gods.

“I think it’s time you tell me the truth, Ren Likui.”

“What do you mean? I’ve told you everything I know. Liu Shi came to the temple to burn incense. I gave instruction about her proper path. That’s all.”

“And yet you call her a snake. Why is that, I wonder? I knew about Shan and second wife’s affair all along.” Inspector Xia didn’t know.

Ren Likui pulled a worried face from his hands. “You did?”

“Yes, and I know much more.”

“I will say nothing. Not unless you produce Shan’s body.”

“Do you mean the body you have hidden under your bed?”

Ren Likui sobbed.

“She tried to seduce me first.” The Daoist monk became a sniveling mess. “But then, she turned on my dear friend. As the saying goes, for a woman to chase a man is like the wind slipping through yarn. My Shan resisted, at first, and I’d like to think it was for my sake, but we were not to be.” He sighed toward the ceiling. “Wine is a poison to the gut, fornication is a steel knife to the bones.”

“Go on.” Inspector Xia’s heart was racing. He coughed into his fist to hide his excitement.

“She wanted Shan to flee Tientsin with her, but he would not think of it. So she found another man, Chu, I believe his name was.”

“Was?”

“Shan lured him to the temple and killed him in a fit of jealousy when he found out she was having an affair with him.”

“Yes, so I’ve heard. Continue.” Inspector Xia bit the inside of a finger.

“She had the heart of a snake. Stole my Shan from me. One day, after the period of clouds and rains were over, Shan came back to me. Distressed.” Ren Likui smoothed the bed’s frayed quilt. “He began telling me everything. How she was trying to squeeze flour from a bullfrog by threatening to tell everyone about their affair. I… he was so vulnerable. I couldn’t help myself.”

“And then?”

“It’s all a blur. At night, demons find me. They torment me. I keep seeing it over, and over again… If I could only sleep.”

“See what?”

“My Shan. When I came to, he was dead. It was as if I could not control my own hands. I cut off his head, wrapped it carefully in wax cloth, and in my finest linen, and… then it was stolen in the night.”

The confession was as expected as a Tientsin summer rain, and the words drenched him head to foot, in exhilaration.

“Why cut off his head?”

“So Liu Shi could never find him. Even in the spirit world.”

“I see.” Inspector Xia had victory at his fingertips. The case was all but solved. What proof was needed when a signed confession was thrown into your lap? In his ecstasy, he stood, pointed an accusing finger. “So your friend Shan first killed Chu in a jealous rage, and then turned on second wife before she could…”

Ren Likui interrupted. “What are you talking about? My Shan had nothing to do with second wife’s death.”

An Inch of Ashes

Shan’s body was discovered in a tub buried beneath Ren Likui’s bed. Ren Likui was found guilty in Zhihli Province Supreme Court for Shan’s murder, and met his gods, and demons, before a firing squad.

In former years, Inspector Xia would have been satisfied that two-thirds of the murderous case was solved, but second wife’s murderer was still not discovered. The Wangs, being an influential family, pressured him and his boss to find the culprit. Summer chilled. Winter arrived with hardly a mention of autumn.

Wang Siwei and his merry huihuir were good to their promise, and found the Wang family runners. Zhou Liang was discovered dead at home from a knife wound. Pang Guang nearly asphyxiated from coal dust fumes in his home on the night before he was to marry. He revived, and implicated himself in the love affair between second wife and Shan, but not with her murder. No more information was forthcoming from little Bangchui, or his family, nor could Inspector Xia learn anything new from He Laofu, and his wife. The watermelon seller was investigated again, but Investigator Xia found no solid proof connecting him to second wife’s murder. At best, he had inadvertently carried her body to his fields, dumping her under a pile of melons. But who placed the body into his cart? Old Xu? Wang Laoye? He could not connect the dots.

SOME LOCAL STORIES say Ren Likui was also convicted of second wife’s murder. Other Tientsin legends say culprits much closer to home were involved. All sources for this true story admit second wife’s love affairs were not as secret as she thought they were.

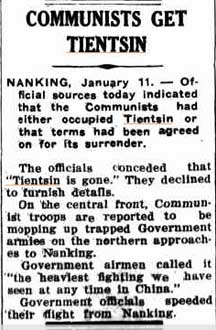

Before the first snow, 1947, two years before Mao’s communist forces swept across China, forcing the Kuomintang to Taiwan, Old Xu was reportedly seen in the Xishi Avenue ghost market, late at night. Solemnly, he stacked paper money into a pile, weeping as he struck match after match, before lighting a small blaze. According to city legends, the paper money smoke flew straight and narrow, all the way to the heavens, and he confessed, as he added the last of the spirit money, that it was Wang Jinyuan’s first wife who ordered him to murder second wife. He also begged the heavens’ forgiveness for murdering Zhou Liang before he could confess to his assistance in hiding second wife’s body, under Old Xu’s direct orders.

After the fire dwindled to ashes, a sudden north wind swept through the ghost market, filling Old Xu’s mouth and throat with ash and hot coals, choking him to death.

This story is based from true accounts from the Ghost Market Human Head case, considered one of the “Eight Strange Cases of the Republic,” according to a radio report from FSM Telecommunications Corporation on Dot FM, records from the Tianjin Museum Archives, story databases Writing Collections and Docin, online directory Tianya, and the Elderly Culture Exchange Report. Most conversations, and some personality traits, including descriptions in this story are imagined, but the facts, the characters involved, the locations, and the harrowing murders, unbelievable as they may seem, are nonfiction.