By C.S. Hagen

TIENTSIN, CHINA – Ligu and Chungu never lingered at market, like other girls their age, hoping to get noticed. When the Zhang sisters grew hungry, they tightened their clothes. Too poor to have their feet bound, they contended themselves with helping mama embroider lotus shoes and trinkets for copper pennies. During a time of near anarchy, as the Qing Dynasty succumbed to Sun Yat-sen’s Republic in 1911, Tientsin’s streets teemed with gangsters, prostitutes, foreign merchants, and revolutionaries, but the Zhang sisters held true to their family’s Confucian values, keeping the “door wind” (门风), or bad reputation, at bay.

The Zhang sisters, Ligu (丽姑), the eldest, and Chungu (春姑), stayed home, as virtuous young girls under the Confucian order. They adhered to the “four virtues,” practicing proper speech and jealously guarding their chastity; they worked diligently, and strived for modesty. Their family was among Tientsin’s poorest classes living in the Heping hutongs, but they didn’t complain even when their father, a rickshaw puller, couldn’t earn enough to put rice on the table.

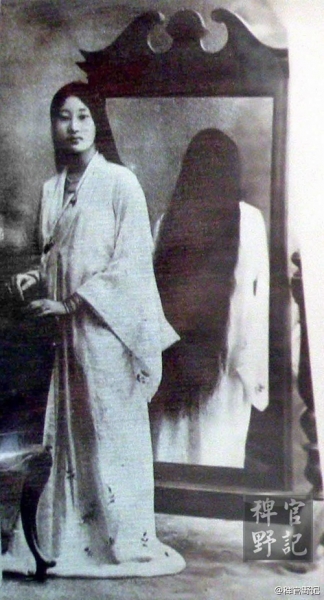

Innocent of the prostitutes and gangsters around them, the Zhang sisters blossomed into young teenagers, catching the eye of a local wealthy mawang, or pimp, Dai Fuyou (戴富有). Dai was more than a pimp, however; he was a “white ant,” a trafficker of young girls sold, tricked, or kidnapped then forced into the prostitution trade, known in Tientsin as the Land of Broken Moons.

Dai schemed. He plotted how to tempt the Zhang sisters into his “wolf’s lair,” according to a November 20, 2013 documentary broadcasted by China Central Television Network (CCTV12), and didn’t find an opening until baba, Zhang Shaoting (张绍庭), lost his rickshaw.

And then Dai set his trap.

The Twin Paragon Sisters (双烈女案) case is documented in part through an unnatural death records book dating to the Ming Dynasty. The book is thick, revealing more than 36,000 women who met grisly ends in attempts to keep their chastity, and reads, according to CCTV12, like a “King of Hell’s Death List.”

The Zhang sisters’ case is also known as one of Tientsin’s “Eight Strange Cases of the Republic.”

Baba

Every time Zhang Shaoting found a little fortune, disaster followed. Much like Old Testament Job. The two men could have been bosom buddies.

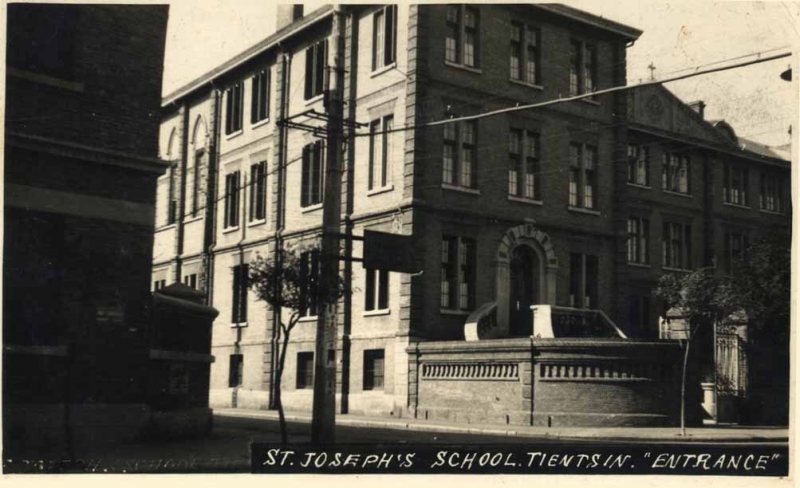

In the late 1890s, Zhang, at 19-years-old, fled his hometown of Nanpi in Hebei Province and took refuge in Tientsin’s Old Xikai District, a 4,000-acre strip west of the old “Celestial City” under French control. (Present day Xikai Catholic Church, Isetan, and Binjiang Road area). He found gainful employment in a ceramics shop, worked hard, and won the shopkeeper’s daughter’s hand in marriage. He was a cautious fellow, submissive, sometimes talkative, according to Nanpi Government reports. Being raised as a devout Buddhist, he was careful to protect his family’s “door wind.”

When Ligu was one-years-old, the first disaster struck.

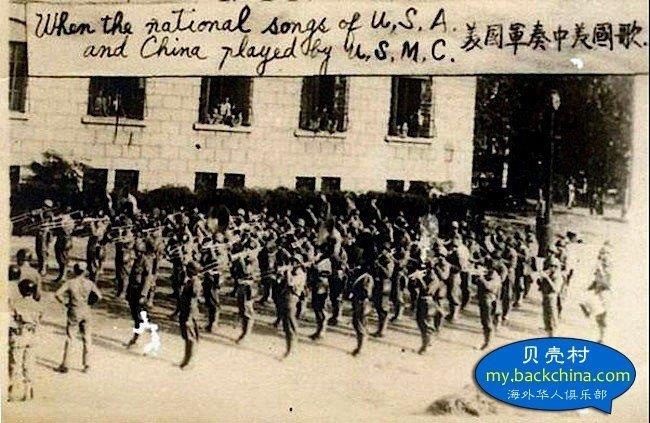

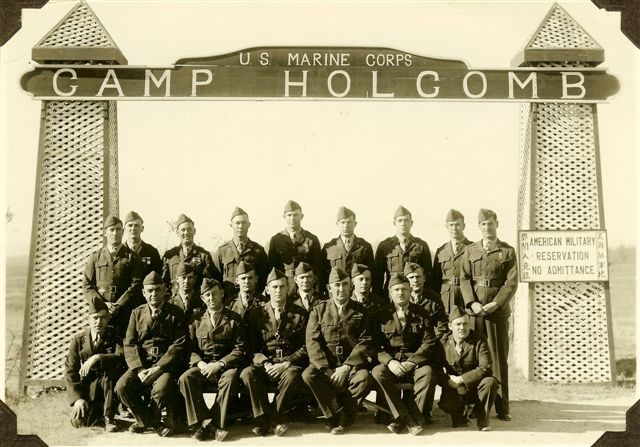

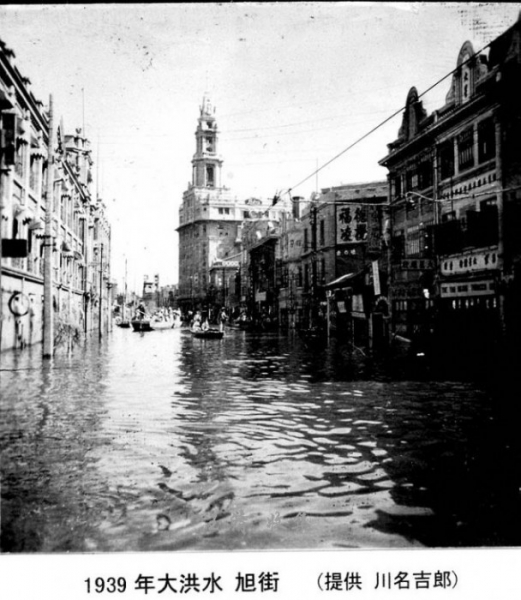

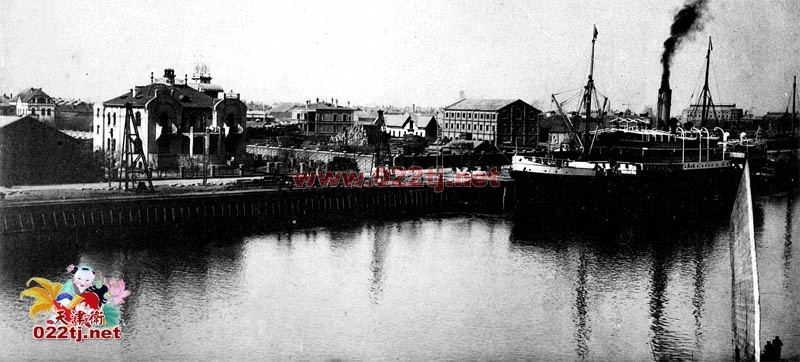

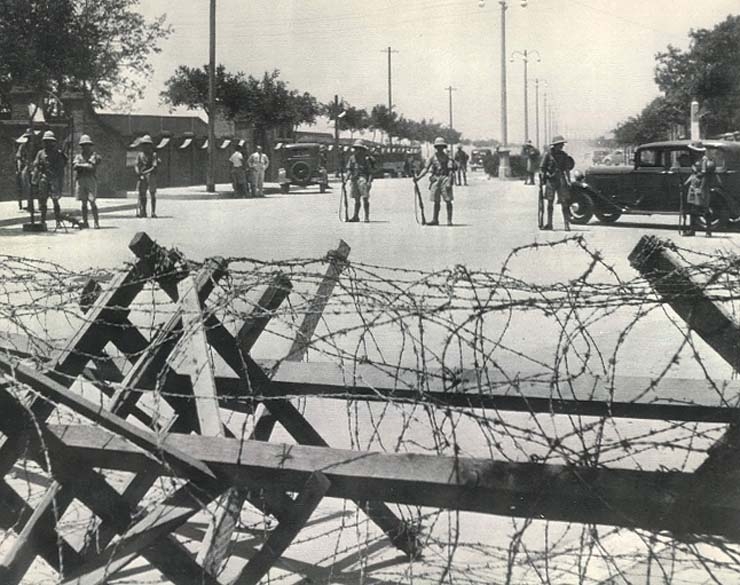

In June 1900 approximately 120,000 Righteous and Harmonious Fists mauled Tientsin, declaring war on colonial foreign powers of the United Kingdom, France, Japan, Germany, Russia, Hungary, Italy, and the United States in what came to be known as the Boxer Rising. Supposedly impervious to bullets through magic charms pasted on their chests and Plum Flower Boxing, the Boxers attacked embassies in Peking, beheaded missionaries across the provinces, slaughtered opium dealers at the port cities, and joined forces with Qing Dynasty Imperial troops to sack the Tientsin Foreign Settlement, an area along Tientsin’s Hai River given to the eight foreign powers through the Unfair Treaties of 1860.

Read more about the Boxers’ Red Lantern Society here.

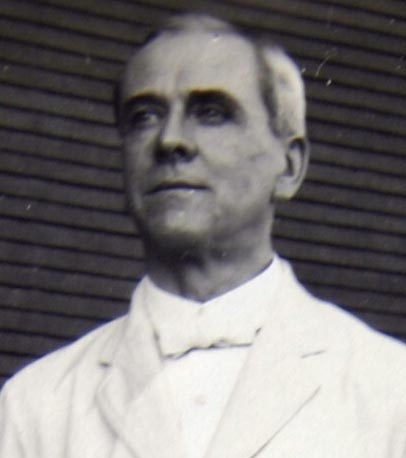

The Eight Allied Nations’ response was harsh. Naval cannons aboard the H.M.S. Terrible and H.M.S. Fame flattened Tientsin’s ancient walls and city, including the ceramics shop in which Zhang worked. Jin Lao, the proprietor, died days after the siege, leaving Jin Shi, his wife, and young daughter stranded.

An uneducated man, Zhang turned to the rickshaw. Grueling work in Tientsin’s hot summers and bitter winters. Lacking money to purchase the vehicle, Zhang was forced to rent. Costs weren’t cheap, according to Michael T.W. Tsin in a book called Nation, Governance, and Modernity in China: Canton 1900-1927.

“Most companies charged a daily deposit of C$5 [five Chinese dollars] plus a rental fee of about C$1 for each rickshaw. The amount was paid by the contractor, who assumed full responsibility for the vehicles. A puller had to pay the contractor a commission for his service, in addition to the cost of leasing the rickshaw.”

In Tientsin, contractors formed guilds to protect their interests, and zealously guarded their rickshaws and fiefdoms on which they moved people and goods.

“The transport workers and the guilds that controlled them, with a history of more than 200 years, were among the oldest and most important participants in the making of the Tianjin [Tientsin] working class,” according to Gail Hershatter in her book The Workers of Tianjin, 1900-1949.

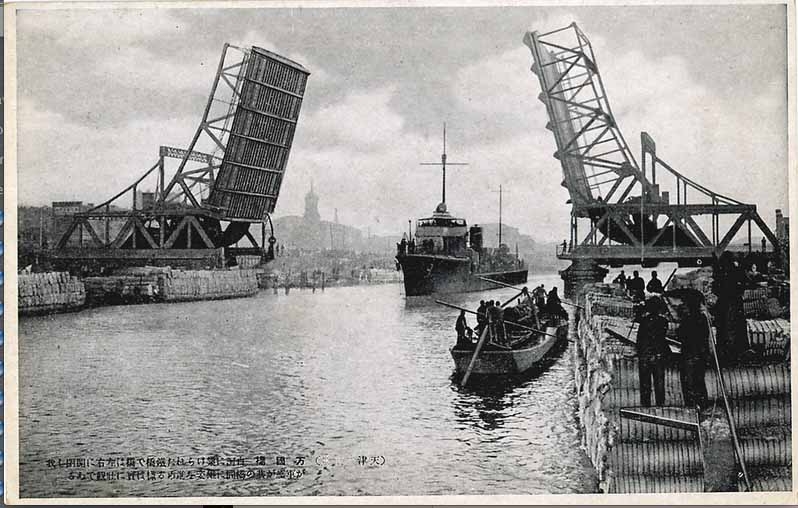

“Tianjin [Tientsin] lived by trade: it was the meeting point of five rivers, an important juncture on the Grand Canal, the loading point for sea shipment of goods from North and Northwest China, the entry point for foreign imports and Shanghai goods, and the major northern station of two railroad lines,”

Freight haulers, rickshaw pullers, and three-wheeled carts all worked for the highly organized guilds frequently fighting each other for turf. Tientsin’s guilds were among the most feared and despised organizations, according to Hershatter.

A puller, such as Zhang Shaoting, was usually charged 60 Chinese cents per shift, which varied from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m., or from 2 p.m. until midnight. Naturally, rickshaw pullers labored at the bottom of Tientsin’s social order, and were affiliated with Dark Drifters, hunhunr, and gangs, such as the Qing Bang and the Green Gang.

“Carters, boatmen, innkeepers, transport workers, brokers – even if innocent, they deserve to be killed,” was a common Tientsin folk rhyme in the early 20th century.

The copper cash strings Zhang brought home were hardly enough for three mouths, and when Chungu was born three years after her elder sister, mama turned to embroidery to make ends meet. Later, she also gave birth to a boy, ensuring the family’s name, but forcing her husband to work longer hours, deteriorating his health.

In the spring of 1916, Zhang’s rickshaw was stolen while he napped. A rickshaw in those days would take a year’s wages to pay for, and Zhang, now nearing 40, became desperate.

Wang Baoshan (王宝山), a Dark Drifter lackey of Dai Fuyou, hurried to his “elder brother” with the news, according to CCTV12. When Dai heard of Zhang’s plight, he sprang his trap. He knew all he needed about the Zhang family, after all, they did not live far away; they were practically neighbors.

Read more about Dark Drifters here.

“Give your daughters in marriage to my two sons, and I will more than settle your score for the stolen rickshaw,” Dai said, according to CCTV12 and Xinhua News. “I can have the marriage contract written up immediately.”

Seeing no way out of his predicament, Zhang agreed, and hurried home with the good news. His daughters were to be wed to wealthy landowners. The Zhang’s family fortune had taken a good turn.

True to his word, Dai soon brought the marriage contract, but found excuses not to sign. “What’s the hurry? We’re all one family now. Listen up, I can do you one better. Since your daughters are now my daughters, and my sons your sons, and because you are not wealthy, why not let your daughters live in my mansion? They will be treated like my own blood, or my name is not Dai.”

Once again, Zhang agreed, and Ligu and Chungu, filial daughters, left with Dai to live in his mansion.

The Wolf’s Den

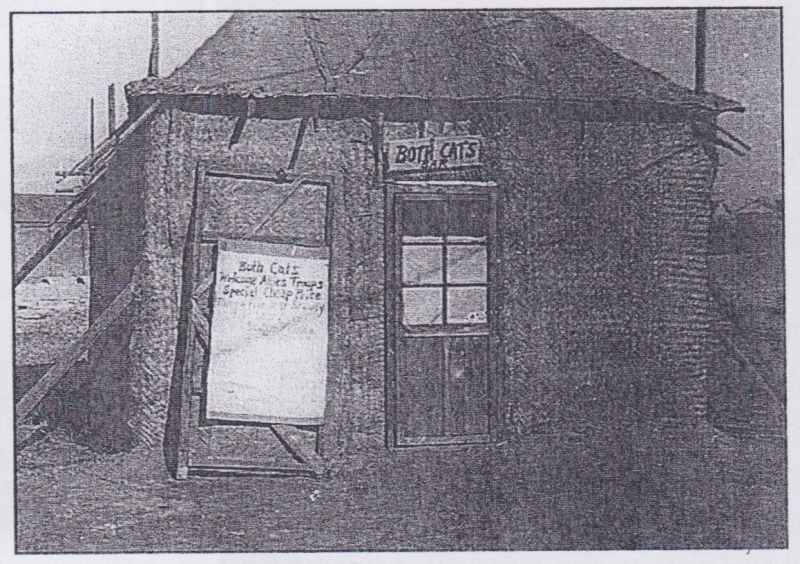

Not long after the Zhang sisters arrived, Dai hired a middle-aged woman to teach the sisters how to sing crude songs, fit only for a teahouse brothel. Daily, men came to listen to the lessons, and Ligu noticed the men speaking excitedly to each other in hushed tones.

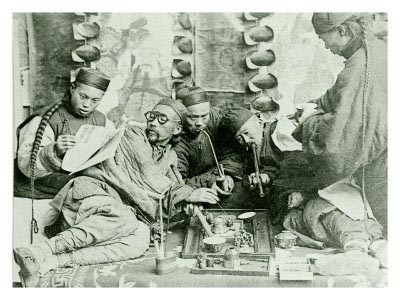

In the Qing Dynasty’s twilight years, teahouses were community centers, nests for gossip and news, but were also podiums for talented artisans, courtesans, and prostitutes to tell stories, recite poetry, sing songs, and tempt possible lovers. Such establishments were hounded by the so-called “mosquito press,” local tabloids who rated the performances, and gave helpful “tips” to anyone wanting to enjoy the “Flower World,” more appropriately known as the Land of Broken Moons. The comings and goings of strange men and heavily painted women at Dai’s mansion increased Ligu’s fears she and her sister had been tricked, according to CCTV12 and Tianjin Museum Archives.

Early one morning Ligu and her sister fled Dai’s mansion, returning home. Ligu found baba sick, too weak for work, but when he heard the news, he was livid.

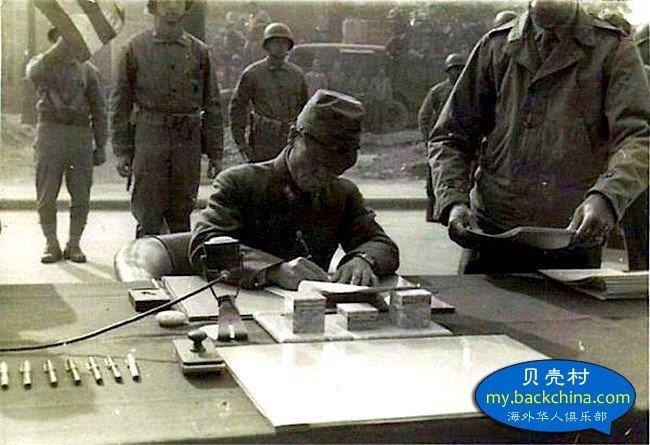

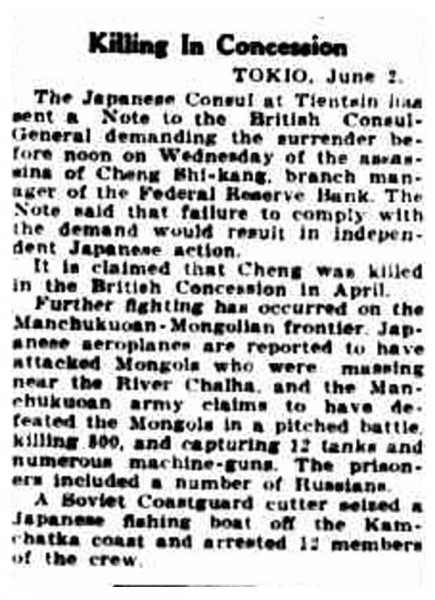

When Dai discovered his sons’ fiancées had ran away, he too was angry. Having such tasty meat so close to his lips could not be forgotten, according to CCTV12. But Dai had laid his trap, and was not deterred. Having in his hands the original unsigned marriage contract, he made a counterfeit document, with all parties’ signatures, and promptly sued Zhang for breach of marriage contract in the Zhili Province Supreme Court.

Upon seeing the signed forged document, and recognizing a man of means, court officials wasted no time in siding with Dai, and ordered the Zhang sisters to return home with Dai to be married to his sons. Dai’s lackey Wang and his two sons also testified the marriage document was authentic, according to CCTV12.

“Dragons breed dragons; a phoenix gives birth to a phoenix. A mouse’s son can dig a hole,” CCTV12 reported, meaning Dai’s sons were as wicked as their father.

Zhang, barely strong enough to walk, spewed blood across the courtroom floor after a coughing fit.

“Zhang’s sudden loss, followed by the elation from arranging his daughters’ marriages, and then the consequent anger at being cheated was too much for Zhang to bear,” CCTV12 reported.

“He became deathly sick and died two days later,” the Xinhua News and online records from the Tianjin Museum Archives reported.

Suicide

After nearly 100 years, a memorial stone dedicated to the Zhang sisters still bears their tragic story. The massive stone was spared the ravages of war and the Cultural Revolution, CCTV12 reported, because a former viceroy of three northeast provinces, Xu Shichang (徐世昌), wrote the story, and a famous politician and calligrapher, Hua Shikui (华世奎), painted the characters.

The Zhang sisters were distraught, characters in the stone read. No one could help them. Their father was dead; their mother was a simple seamstress.

With Tientsin law on their side, lackey Wang and Dai’s two sons pounded on the Zhang family door, demanding that the sisters report to the Dai household the next morning. If not, both would be sold to a brothel, CCTV12 reported, which was a fate the sisters already suspected.

All night long the Zhang sisters cried to the heavens and to the earth, with no response, the memorial stone read. Nearing dawn on March 17, 1916, Ligu, who was 17-years-old, turned to her 14-year-old sister.

“The life of a whore is no life for us,” Ligu said. “It is better we die than to let the door winds befoul the Zhang family name.”

Choking on her tears, Chungu agreed.

Ligu procured three packs of red phosphorus matches from under the bed. One by one, she cut the tips off and placed the match heads into a pile. She poured two cups of kerosene and dumped the match heads into the cups, creating a powerful poison.

“You must drink this.” Ligu handed her younger sister a cup. “The fate of a whore is worse than these few minutes of discomfort. If we must die then that is our fate, but we must not ever slight the Zhang family’s name.”

Ligu drank down the poisonous concoction. Chungu hesitated.

“I heard those who commit suicide will go to hell and be tortured,” Chungu said.

“Do not be afraid,” Ligu said. “Even in death we will leave behind our innocent bodies.”

Chungu raised the cup to her lips, obeying her big sister and crying as she gulped kerosene and match heads down.

Pain didn’t set in for two minutes, the memorial stone read, and then the sisters’ stomachs began to roil. Both fell to the ground, screaming in pain, waking mama and neighbors who hurried to discover the commotion.

Mama urged the girls to drink water. Both refused. Ligu convulsed. Blood leaked from her eyes and mouth. And then she lay still.

“Even in death, we will leave behind our innocent bodies,” neighbors reported Chungu said. And then, with a final, weak cry, Chungu followed her elder sister into the afterlife.

The Aftermath

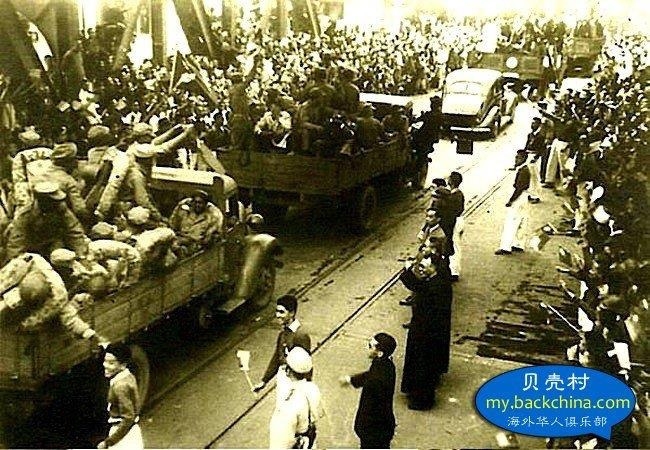

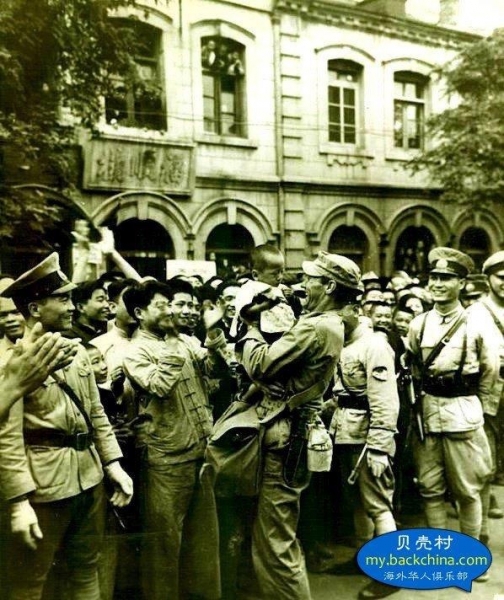

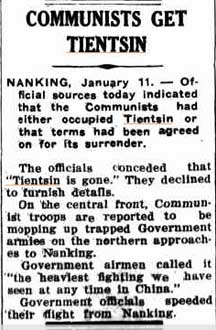

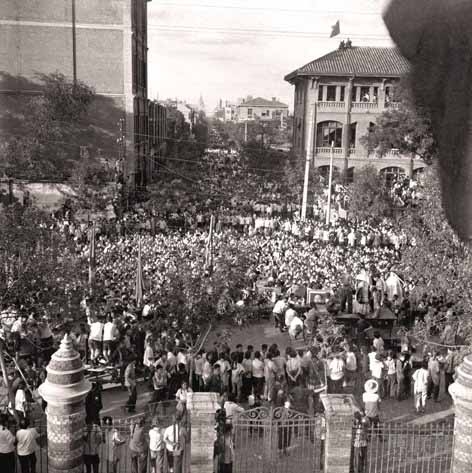

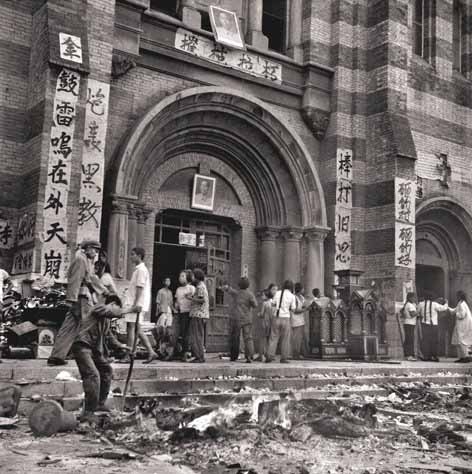

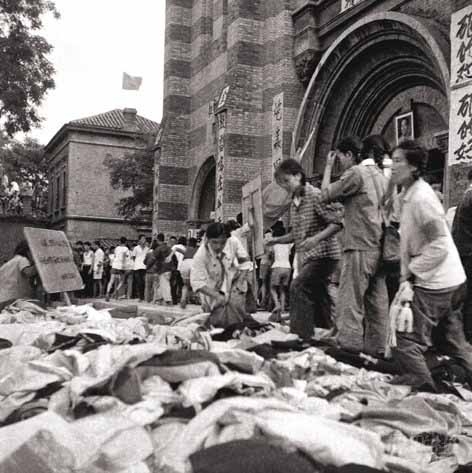

The Zhang sisters’ tragic story spread like wildfire through Tientsin, alerting young and old, rich and poor, alike. Thousands took to the streets in protest of the court’s decision.

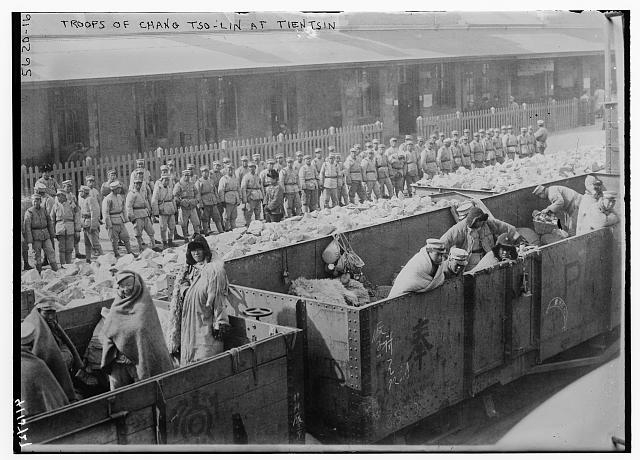

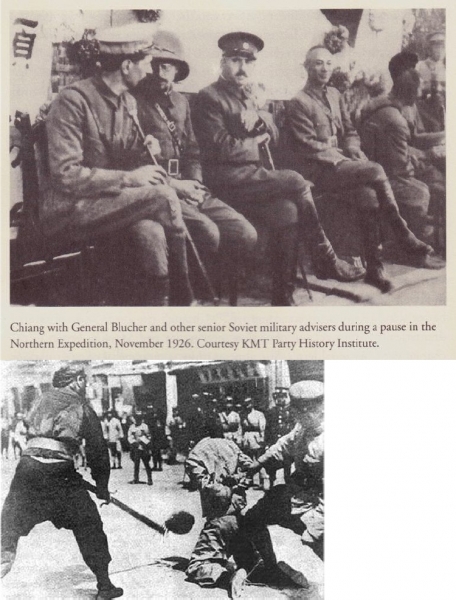

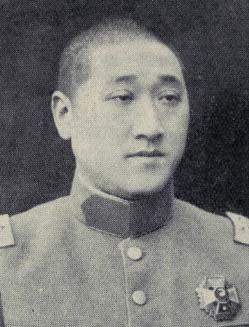

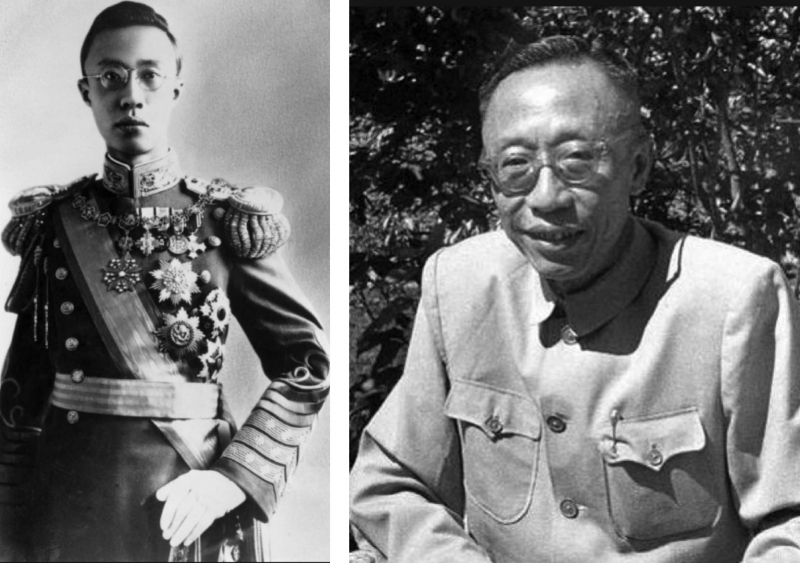

News of their double suicide soon reached the ears of Xu Shichang, a future Nationalist president during the Warlord Era, and Hua Shikai, a Tientsin native, and former military minister for Qing Dynasty princes. After the revolution in 1911, Hua retired to Tientsin, bought a house in the Italian district, and became a renowned calligrapher.

One of the four famous ministers of the late Qing Dynasty, Zhang Zhidong (张之洞), also heard of the Zhang sisters’ suicide pact, and was moved, not only because they shared the same surname and hometown, but because of the girls’ adherence to Confucian principals in a time when most Tientsin natives could not afford to.

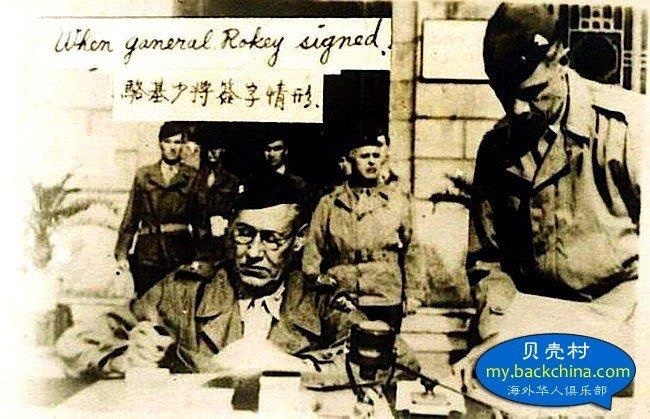

Hua, Xu, and Zhang Zhidong publicly damned the Tientsin courts, and demanded Dai’s arrest, according to Tianjin Museum Archives. The fragile Nationalist government, in only its fifth year since the revolution, grew fearful of unrest. All attempts to arrest Dai failed; the white ant escaped. Protesting crowds grew larger.

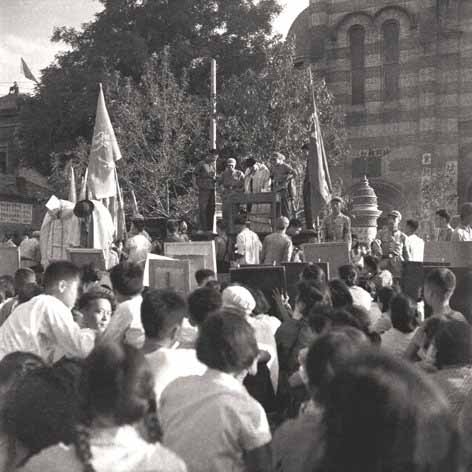

Before the third day after death, when the spirits return to collect monies for heaven, Yang Yide (杨以德), the Zhili Province police minister, scripted province-wide arrest warrants for Dai, and tried to appease the populace by collecting monies from local merchants and gentry for a proper burial, according to the Tianjin Museum Archives.

“Funerals, like weddings, could be a ruinous expense,” Hershatter wrote in her book The Workers of Tianjin, 1900-1949. “Families went into debt to buy burial clothes and to rent a burial plot for the deceased… ; to do otherwise would violate the codes of filial piety and invite bad luck and the scathing judgment of the neighbors.”

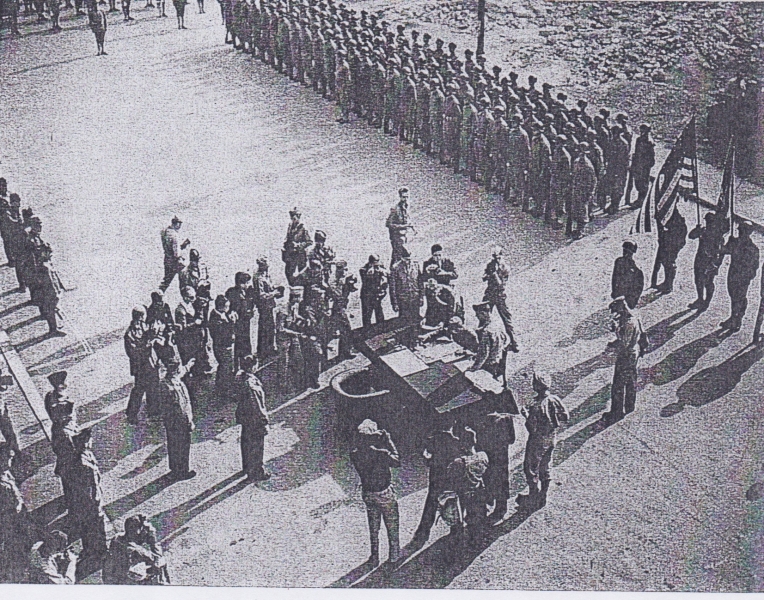

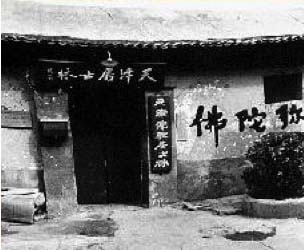

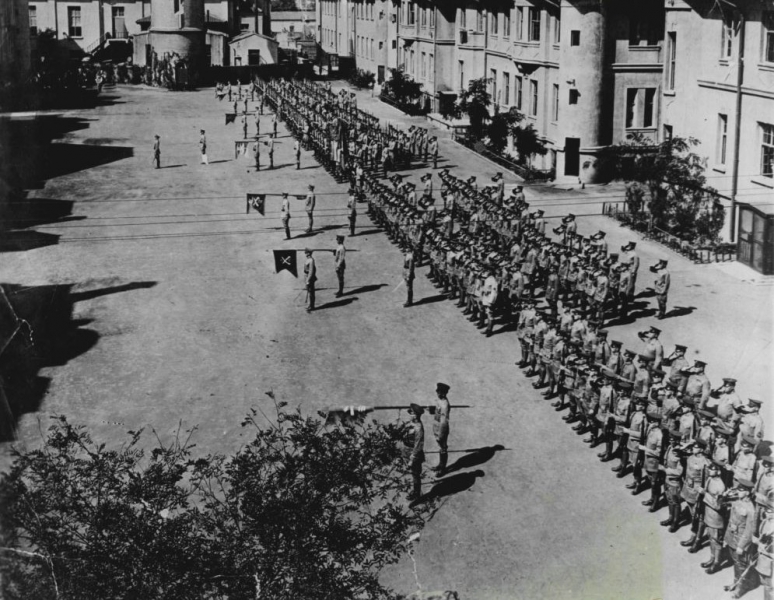

When the burial day arrived, more than a thousand people joined the funeral parade. Musicians were hired. Professional criers wailed at the parade’s tail. Soldiers in full military regalia cleared the streets. Relatives from Nanpi, now known as Dongguang County, made the journey, and the largest, most extravagant coffins were hoisted by eight pallbearers each. The funeral parade started in the western part of old Tientsin, circled the city, and ended on present day Xiguan Avenue. The sisters were laid to rest inside a Female Paragon Temple, or temples for strong women.

Before 1911, Female Paragon Temples, Lienv Ci (烈女祠), were reserved primarily for female martyrs defending piety and chastity. Tientsin’s Paragon Temple at one time housed more than thirty graves, including the Zhang sisters, and held sixty-one tablets honoring those who died while defending their innocence.

On May 4, 1919, the wife of the future first premier of communist China, Deng Yingchao, declared women’s equality across China, consequently abolishing thousands of years of feudalism and Confucian thought. Tientsin’s Paragon Temple was destroyed to make room for a movie theater soon after the declaration, according to the Tianjin Museum Archives. A hutong sprouted around the theater, and became known as the Female Paragon Temple Hutong (烈女祠胡同). Most, if not all of the hutong, is now gone.

According to the Tianjin Museum Archives, the Zhang sisters’ remains and their headstones were relocated to Nanpi before the theater was constructed. Monies left over from police collections were used to provide for widow Jin and their brother, who also returned to Nanpi under Zhang Zhidong’s protection.

In later years, the Zhang sisters’ tragedy was featured in numerous Peking operas and plays across the nation. The stone monument telling the sisters’ story sits in Tianjin’s Zhongshan Park, protected under a small, grey-roofed pavilion to this day. How the stone survived Tientsin’s warlords and revolutions isn’t important. Its facade has smoothed with time; the characters are chipped, and difficult to read, but it remains as an affirmation that goodness, sometimes, is stronger than evil.